The market valuation exceeds the technical cost

Notes on Competitive Trade Theory Donald R. Davis

Professor of Economics

Columbia University

Spring 2001

© Donald R. Davis, All Rights Reserved

Table of Contents

V. The Specific Factors Model 36

VI. Policy in the Perfectly Competitive World 40

and Foreign Trade.

I. Introduction: Microeconomic Foundations of Competitive Trade Theory

If countries trade, do they benefit from this trade or are they harmed by it? Do some countries gain at the expense of others? Will they be best off with free trade or by implementing taxes and other restrictions on trade? Will the market, left alone, lead to the best solution, or are there market failures? If there are market failures, are there measures the government can (or will) take to reach such an optimum? How do we decide which measure is appropriate? These are questions regarding the welfare results of trade and the potential for improving it via commercial policy.

Trade theory, as economic theory, has typically been distinguished according to positive or normative analysis. In this framework, positive theory seeks to understand the determinants of the pattern of trade and the terms at which trade takes place. The normative seeks to ascertain whether agents and/or countries gain or lose by trading. This seems a worthwhile distinction -- it is possible to determine the results of certain conditions apart from whether they are desirable or not. If anything, the reader is advised to be careful that those who assert the distinction apply it scrupulously.

INDIVIDUALS

Objective: Each individual is assumed to maximize utility. At this level of generality, we do not yet specify all of the determinants of utility, except to note that it will include consumption of final goods. For example, utility could be extended to depend on the amount of work one has to do, the utility of others, the level of government spending on public goods, or anything else that they may care about.

4

it can take. We note some of the more important ones here. It can decide whether there will be any international trade at all (although even here its hand may not be entirely free, as some economists have developed formal models of smuggling!). It can impose taxes or subsidies on production or consumption of one good or the other, to encourage or discourage its production or consumption. It can impose taxes or subsidies on the use of one factor or another, in one industry or many. It can impose tariffs, voluntary export restraints, quotas, and many other measures.

5

Yet it should be so obvious to you that it is beneath wonder. Of course! If I can change my choice by a little and the benefits exceed the costs, then I should do it. If the costs exceed the benefits, maybe I'd better retreat a little. Stand still when there is no further gain to be had.

6

We will state the basic principle of optimality and then look at a few examples to be sure that we understand it. We must distinguish (1) market opportunities to trade from the (2) private willingness (or ability) to substitute. Whew! What is that? Basically, we cannot be at an optimum if the rate at which (secret?) agents are willing to trade is different form the rate at which the market allows them to trade. To understand this, we must turn to examples.

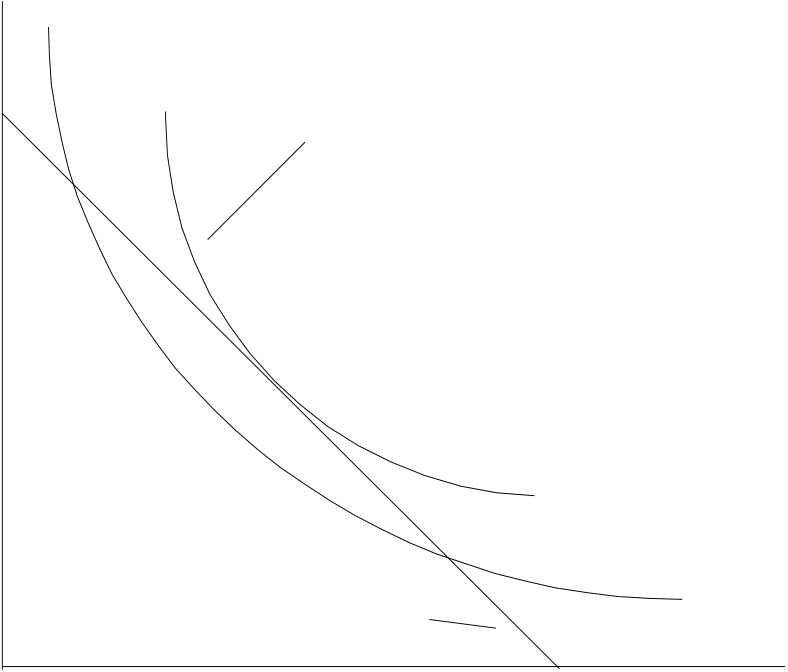

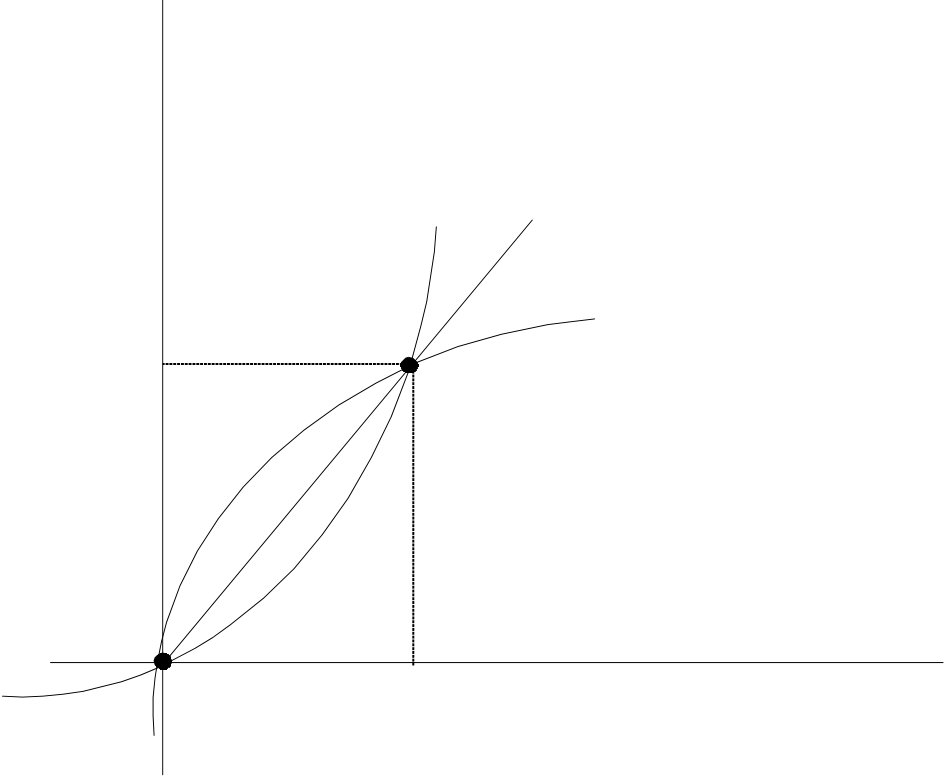

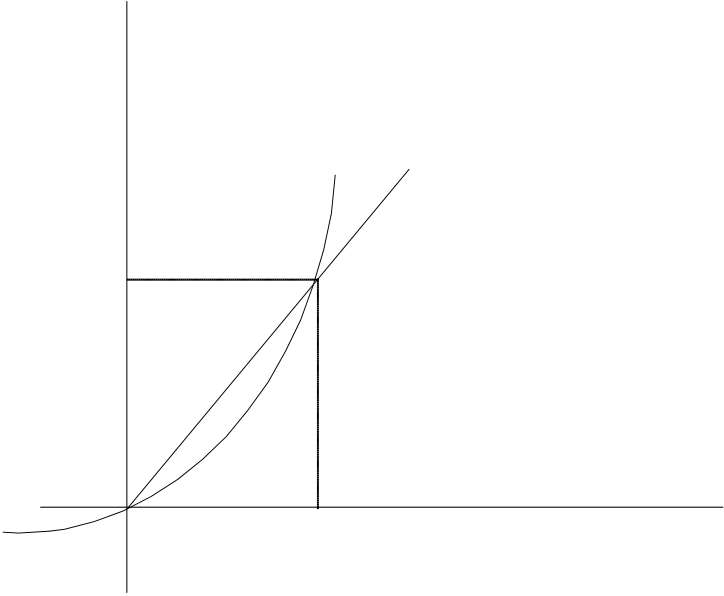

We will examine this question graphically and analytically in three contexts: (1) The consumer choice problem between two goods; (2) the producer's choice of factor inputs to minimize cost; and (3) the producer's choice of optimal output mix.

Let's return to the consumer's problem now. As before, we look at point B, where the indifference curve is steeper than the budget line. Since the indifference curve is steeper there than the budget line, we know that the slope of the indifference curve (MRS) is greater than the slope of the budget line (the relative price), i.e. MRS > P. Thus, the consumer's private valuation of X is greater than the market cost of X. Not surprisingly, then, the consumer desires to take advantage of this to trade in the market to obtain more X. The consumer stops trading for more X just when the private valuation of X (the MRS) is equal to the market cost of X (the price ratio). Now we see what the tangency condition means. The private willingness to trade (slope of the indifference curve, i.e. the MRS) just equals the market opportunity to trade (slope of the budget line, i.e. the price ratio).

How can we be sure that we don't move past the optimum? Just look at a point on the budget line to the southeast of the optimum. We see that the indifference curve there cuts the budget line with a slope less steep than the budget line. That is MRS<P. The consumer's private valuation of X is less than the market cost of X. The consumer now trades for more

| K | � | B |

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| � | |||||||

| Isoquant | |||||||

| L | � |

|

|||||

|

|||||||

First we want to define two terms. An allocation of goods among individuals is said to be pareto optimal (also pareto efficient) if it is impossible to redistribute them in such a way as to improve the situation of at least one without worsening the situation of someone else. In comparing two allocations, an allocation A is said to pareto dominate an allocation B if some people are better off at A than B and no one is worse off.

Let us turn to the power of the idea of pareto optimality. Consider an allocation that is not a pareto optimum. By definition, there exists an allocation in which some people can be made better off without others being made worse off. On first blush, it would appear crazy to prefer the first allocation to the pareto optimal one. This is the power of the concept of pareto optimality: if we are not at a pareto optimum there always exists an allocation that could help some without hurting others (maybe the first group could even share some of their gains so that everyone benefits).

The question of actual compensation is very important. If you wonder why the prescriptions of economists (such as those articulated in this course) are too infrequently heeded, you might take a first look at the question of actual compensation. In real-world particular policy choices, there will typically be gains by some at the expense of others; the fact that compensation for the losses is infrequently forthcoming may help to explain why the economist's "first-best" option is often neglected. The problem, though, is thorny. Why should the initial distribution be given priority over the resulting one, so that in switching compensation is required? Why should we compensate those who lose via trade in a manner different than those injured by economic shifts of a purely domestic manner? Does this invite appeals for compensation rather than encourage economic adjustment? How is this general problem dealt with in trade theory?

Unfortunately it becomes too cumbersome to incorporate these (very serious) issues explicitly in every model that we develop. As it turns out, we abstract away from most of these problems via a device that we will articulate later. The advantage of this is that it allows us to take a detailed look at problems that are already very complex without these additional complications. These will be left as distributional issues that each country must work out in its own fashion. Of course, in thinking about real-world controversies, we must always have these problems in mind.

Now consider a single point on the PPF. If this was the amount that we produced of the only two goods, then we could again form an

12

Principle of the Invisible Hand

Arguably the single most important result in all of economics is Adam Smith's Principle of the Invisible Hand. What does it say? It claims that individuals as consumers and producers, each pursuing her own interest as she sees best, wholly ignorant of the aims and desires of others, reacting only to externally given prices, will attain a social outcome that cannot be improved upon. This is an astounding, almost literally incredible claim. If it were true, we could dispense not only with any government intervention, but the omniscient social planner as well -- there would be nothing for her to do that could improve on the outcome the market yields.

Earlier we discussed the conditions for optimum as the equality between market opportunity and private willingness to trade. Now we must amend this. Implicitly we assumed that the decision maker perceived the same private costs and benefits as the true social costs and benefits. The amendment that we must offer is that the market opportunity to trade must reflect true social costs and benefits; in such a case we can be sure that decentralized decision makers will make precisely the same decision as the social planner would.

When Private Cost/Benefit Diverges from Social Cost/Benefit

II. RECIPROCAL DEMAND AND THE WORLD TRADING EQUILIBRIUM

Introduction

Assumptions on Preferences

Most of the literature on international trade has focussed on the

effects of different production structures on trade. The representation

of individual consumers and their preferences is, in most instances,

very rudimentary. To outline the principle results of this body of

theory, we are obliged to follow the assumptions typically made within

it. But the reader

15

In general, countries need not maintain balanced trade. A country that is running a trade surplus will be accumulating assets or claims on the rest of the world; correspondingly, countries running trade deficits will be financing this by selling assets to the rest of the world. These concerns of the composition of the balance of payments are of great practical import. However, they are the province of the branch of international trade dealing with monetary issues (sometimes called open economy macro). In most, if not all, of the material that we will cover in this course, we are abstracting from this set of problems to concentrate on what is typically termed the "real" side of international trade. (The contrast is similar to the difference between macroeconomics and general equilibrium microeconomics).

16

|

Y |

|

UA | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Y �

| Y |

|

|

E* Y | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||||

| � |

|

X | P T | � | M Y | |||

!1 * |

||||||||

X |

Exp |

|

||||||

the balanced trade constraint). The equilibrium is as depicted in the figure.

We can perform a similar experiment for the foreign country, tracing out the offer of exports and imports at each price. Obviously, our full equilibrium requires a price that matches our desired imports with their exports and vice versa. This is represented as the intersection of the two offer curves.

M Y E* Y

| E1 | EEq. | E X M * |

|

|---|---|---|---|

Imp

Imp