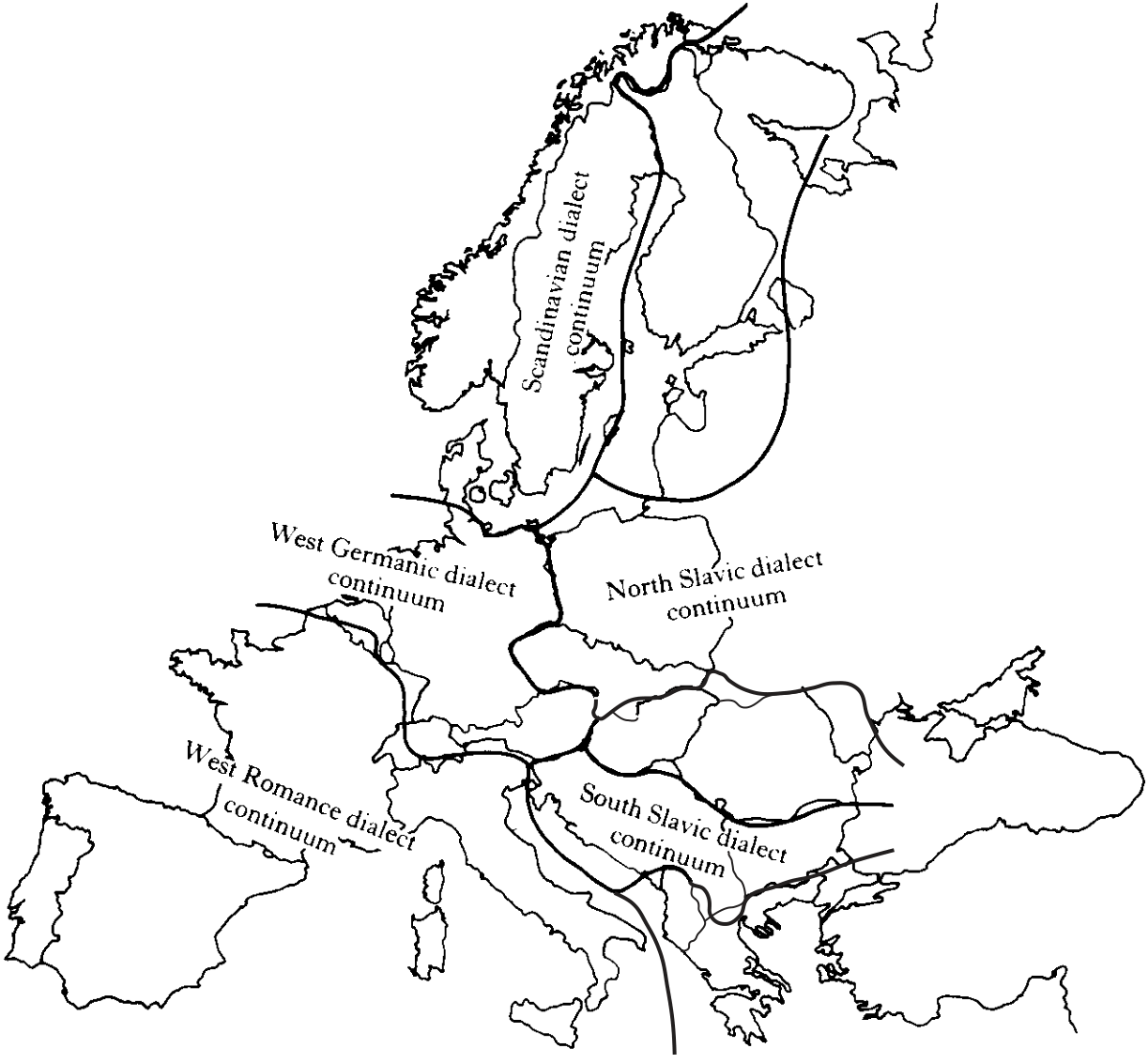

Swedish and danish the north slavic dialect continuum

DIALECTOLOGY

published by the press syndicate of the university of cambridge The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge cb2 1rp, United Kingdom

cambridge university press

The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge cb2 2ru, United Kingdom 40 West 20th Street, New York, ny 10011–4211, USA

10 Stamford Road, Oakleigh, Melbourne 3166, Australia

Typeset in Times 9/13 [gc]

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

background

1 Dialect and language 3 1.1 Mutual intelligibility 3 1.2 Language, dialect and accent 4 1.3 Geographical dialect continua 5 1.4 Social dialect continua 7 1.5 Autonomy and heteronomy 9 1.6 Discreteness and continuity 12 Further information 12

3.3 Generative dialectology 39

3.4 Polylectal grammars 42

4.3 Representativeness 47

4.4 Obtaining data 48

5 Social differentiation and language 57

5.1 Language and social class 57

5.4.2 Social networks 64

5.4.3 Individual characteristics 67

6.1.2 Linguistic change 72

6.1.3 Phonological contrast 73

6.3.1 Stylistic variation 82

6.3.2 The role of sex 83

spatial variation

7 Boundaries 89 7.1 Isoglosses 89 7.2 Patterns of isoglosses 91 7.2.1 Criss-cross 91 7.2.2 Transitions 93 7.2.3 Relic areas 94 7.3 Bundles 94 7.4 Grading of isoglosses 96 7.5 Cultural correlates of isoglosses 100 7.6 Isoglosses and dialect variation 103 Further information 103

Contents

9.3 Handling quantitative data 135

9.4.4 Correspondence analysis of the matrix 144

9.4.5 Linguistic distance and geographic distance 147

10.2 Innovators of change 153

10.2.1 A class-based innovation in Norwich 153

11 Diffusion: geographical 166

11.1 Spatial diffusion of language 167

11.6 Cartographical representation of spatial diffusion 176

11.6.1 The Norwegian study 177

Further information 189

References 190

ix

Maps

11-9 (sj) in Brunlanes, speakers aged over 70 179

11-10 (sj) in Brunlanes, speakers aged 25–69 180

1-1 The initial linguistic situation in Jamaica page 8 1-2

The situation after contact between English and

Creole speakers 8 1-3 West Germanic dialect continuum 10 1-4

Scandinavian dialect continuum

11 5-1 The (æ) variable in Ballymacarrett, The Hammer and

Clonard, Belfast 67 6-1 Norwich (ng) by class and style 71 6-2 Norwich

(a�) by class and style 71 6-3 Norwich (o) by class and style 73 6-4

Norwich (ng) by age and style 78 6-5 Norwich (e) by age and style 80 6-6

Norwich (ir) by age and style 81 6-7 New York City (r) by class and

style 83 9-1 Multidimensional scaling of northwestern Ohio informants

146 10-1 Representation of a typical variable 154 10-2 Class differences

for the variable (e) in Norwich 155 10-3 Sex and age differences for two

variables in

Ballymacarrett, Belfast 156 10-4 Use of couch and

chesterfield by different age groups 159 10-5 Progress of

lexical diffusion on the assumption that

diffusion proceeds at a uniform rate 162 10-6 Progress of lexical

diffusion in the S-curve model 163 10-7 Speakers in the transition zone

for variable (u) 164 11-1 /æ/-raising in northern Illinois by size of

town 176

xi

Dialectology, obviously, is the study of dialect and dialects. But what exactly is a dialect? In common usage, of course, a dialect is a substandard, low-status, often rustic form of language, generally associated with the peasantry, the working class, or other groups lacking in prestige. dialect is also a term which is often applied to forms of lan-guage, particularly those spoken in more isolated parts of the world, which have no written form. And dialects are also often regarded as some kind of (often erroneous) deviation from a norm – as aberrations of a correct or standard form of language. In this book we shall not be adopting any of these points of view. We will, on the contrary, accept the notion that all speakers are speakers of at least one dialect – that standard English, for example, is just as much a dialect as any other form of English– and that it does not make any kind of sense to suppose that any one dialect is in any way linguistically superior to any other.

1.1 Mutual intelligibility

It is very often useful to regard dialects as dialects of a language.

Dialect and language

definition, though, they are mutually intelligible. Speakers of these three languages can readily understand and communicate with one another. Secondly, while we would normally consider German to be a single language, there are some types of German which are not intelligible to speakers of other types. Our definition, therefore, would have it that Danish is less than a language, while German is more than a language.

1.3 Geographical dialect continua

books, and literatures; that they correspond to three separate nation states; and that their speakers consider that they speak different languages.

Dialect and language

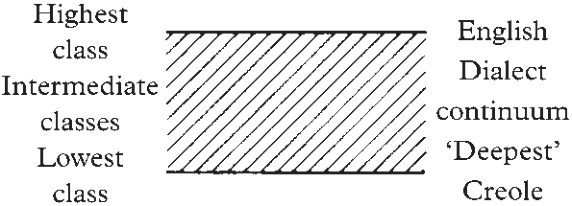

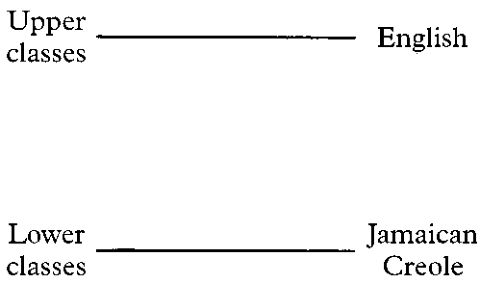

1.4 Social dialect continua

but the fact that such continua exist stresses the legitimacy of using labels for vari-eties in an ad hoc manner. Given that we have dialect continua, then the way we divide up and label particular bits of a continuum may often be, from a purely linguistic point of view, arbitrary. Note the following forms from the Scandinavian dialect continuum:

| (1) | hɑ | sɔm et �ɑm�ɑlt | �ɑusabɑin/ | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (2) | hɑr | jɑ intə sɔ myk�ət | sɔm et �ɑm�ɑlt | ||

| (3) |

|

hɑr |

|

sɔm et �ɑm�ɑlt | |

| (4) | hɑr | e� iç�ə sɔ myç�ə | sɔm et �ɑm�ɑlt | ||

| At home | have |

|

|

Dialect and language

tak wan mofo, Say the words,

ala mi mati, you all my friends,

tak wan mofo, say the words.m’go, I’ve gone,

m’e kon . . . I come . . .

| It’s my book | ||

|---|---|---|

| its mɑi buk |

|

|

| iz mɑi buk |

|

|

| iz mi buk | ||

| ɑ mi buk dɑt |

|

|

| ɑ fi mi buk dɑt | mi nɑ bin �et non |

|

Since heteronomy and autonomy are the result of political and cultural rather than purely linguistic factors, they are subject to change. A useful example of this is pro-vided by the history of what is now southern Sweden. Until 1658 this area was part of Denmark (see Map 1-2), and the dialects spoken on that part of the Scandinavian

9

formerly Danish territory

10

dialect continuum were considered to be dialects of Danish. As the result of war and conquest, however, the territory became part of Sweden, and it is reported that it was a matter of only forty years or so before those same dialects were, by general consent as it were, dialects of Swedish. The dialects themselves, of course, had not changed at all linguistically. But they had become heteronomous with respect to standard Swedish rather than Danish (see Fig. 1-4).

We can now, therefore, expand a little on our earlier discussion of the term ‘lan-guage’. Normally, it seems, we employ this term for a variety which is autonomous together with all those varieties which are dependent (heteronomous) upon it. And just as the direction of heteronomy can change (e.g., Danish to Swedish), so formerly heteronomous varieties can achieve autonomy, often as the result of political devel-opments, and ‘new’ languages can develop. (The linguistic forms will not be new, of course, simply their characterisation as forming an independent language.) Until the beginning of the nineteenth century, for instance, the standard language used in Norway was actually Danish, and it was only with the re-emergence of Norway as an independent nation that a distinct, autonomous standard Norwegian was developed. Similarly, what we now call Afrikaans became regarded as an independent language (and acquired a name, and an orthography and standardised grammar of its own) only in the 1920s. Prior to that it had been regarded as a form of Dutch.

said that ‘a language is a dialect with an army and a navy’. There is considerable truth in this claim, which stresses the political factors that lie behind linguistic autonomy. Nevertheless, the Jamaican situation shows that it is not the whole truth. Perhaps a time will come when Jamaican Creole will achieve complete autonomy, like Norwegian, or shared autonomy, like American English. Certainly there are educational grounds for suggesting that such a development in Jamaica would be desirable.

It is also possible for autonomy to be lost, and for formerly independent varieties to become heteronomous with respect to other varieties. This is what has happened to those varieties of the English dialect continuum spoken in Scotland. Scots was formerly an autonomous variety, but has been regarded for most purposes as a var-iety of English for the last two hundred years or so. Movements are currently afoot, however, linked to the rise of Scottish nationalism, for the reassertion of Scottish English/Scots as a linguistic variety in its own right, and it is possible that some form of Scots will achieve at least semi-autonomy at some future date.