Vol 54 No 2, June 2020

|

–5 |

λ

0.5 |

|

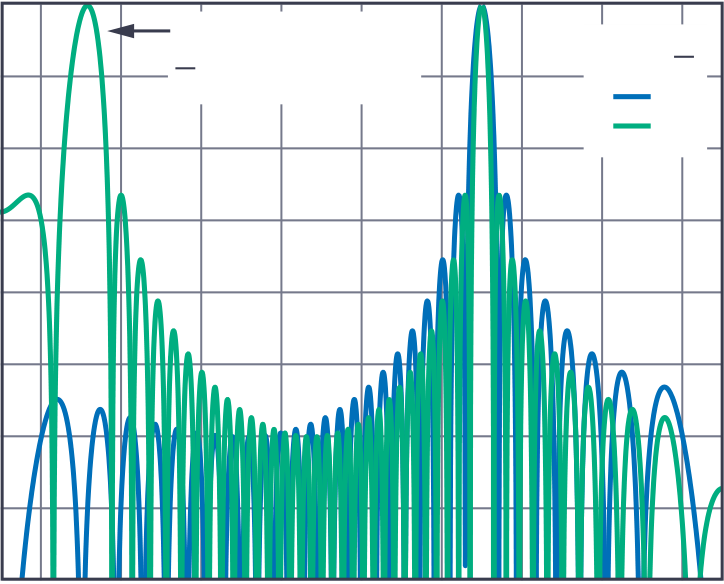

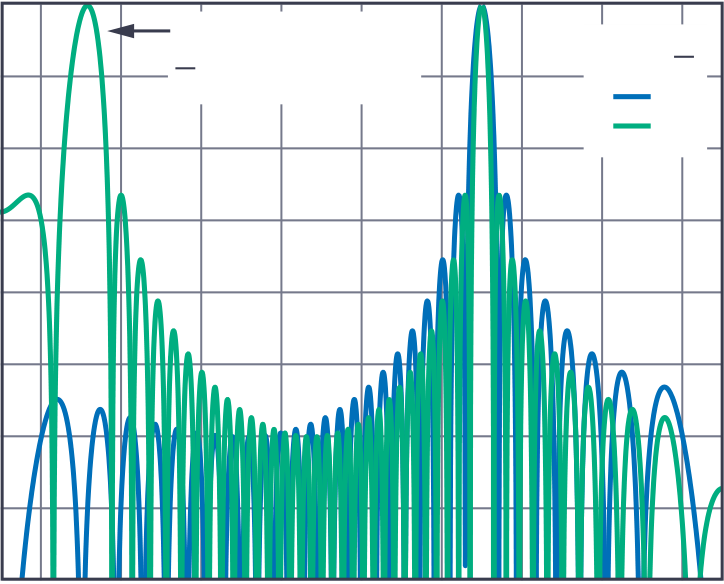

squint. Grating lobes can be hard to visualize, so we’ll draw on

their similarity

|

|

|

|

–30 |

| –35 |

An Introduction to Grating Lobes

|

–40 |

Analogy to Sampled Systems

An analogy to visualize grating lobes is to think of aliasing in a

sampled system. In an analog-to-digital converter (ADC), undersampling

is often used when frequency planning a receiver architecture.

Undersampling involves purposefully reducing the sample rate (fS) such

that the sampling process translates frequencies above fS/2 (the higher

Nyquist zones) to appear as aliases in the first Nyquist zone. This

causes those higher frequencies to appear as if they were at a lower

frequency at the output of the ADC.

| θ = arcsin |

|

m× |

|

|

(5) |

|

∆Φ |

× λ d

|

(2)

|

|

| 2� |

|

|

|

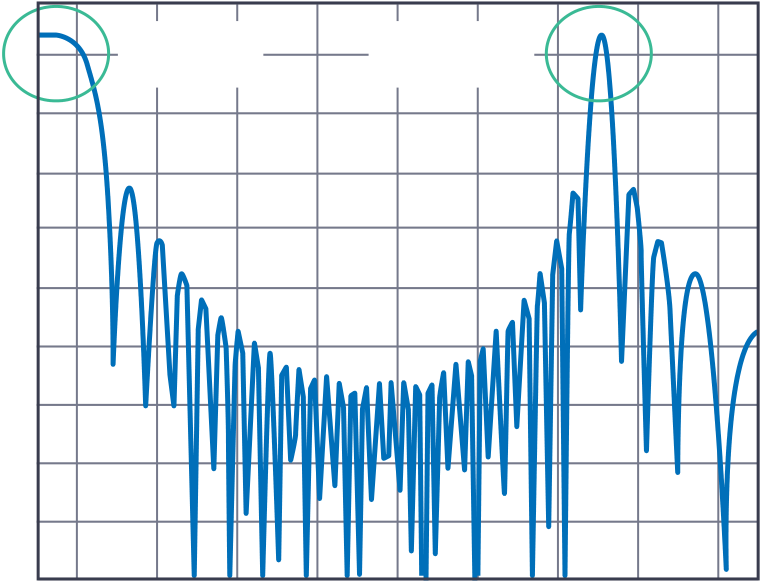

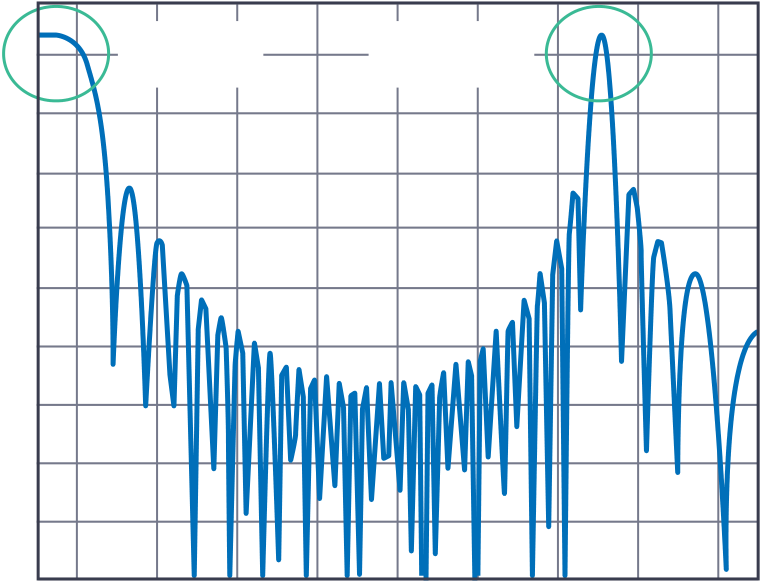

exist. For example, if λ/d = 0.66 (that is, d = 1.5λ), then real

arcsin solutions

|

would exist for m = 0 and for m = ±1. That m = ±1 is the second

solution, which is

|

|

If we do so, then all the spatial images (that is, m = ±1, ±2, etc.)

will produce non-real arcsin results, and we can ignore them. But if we

can’t do this, and therefore some values of m > 0 produce real arcsin

results, then we end up with multiple solutions: grating lobes.

| –5 |

| –15 |

| –25 |

| –35 |

| –80 |

–60 |

–40 |

–20 |

0 |

20 |

40 |

60 |

80

|

Angle (°)

θ = arcsin m , for ∆Ф = 0 λ

d

So for Example: λ/d = 0.66

0 = Actual Lobe

X = Grating Lobes

| We saw ∆Φ range from 0 to ±π as the main

lobe deviated from mechanical |

| boresight. Therefore, |

10 |

| 5 |

| will range |

| –10 |

|

(8) |

–20 |

| argument > 1 for all |m| ≥ 1. Consider two

cases: |

It is an interesting trade-off that will be explored in the next

section.

Element Spacing Considerations

This dmax is the condition for no grating lobes in the reduced scan

angle (θmax), where θmax is less than π/2 (90°). For example, if the

signal frequency is 10 GHz and we need to steer ±50° without grating

lobes, then the maximum element spacing is:

There are also antenna architectures worth noting that attempt to

overcome the grating lobe problem by producing a nonuniform element

spacing. These are categorized as aperiodic arrays, with spiral arrays

as an example. For mechanical antenna construction reasons, it may be

desirable to have a com-mon building block that can be scaled to a

larger array, but this would produce a uniform array that is subject to

the grating lobe conditions described.

Beam Squint

| –5 |

–5 |

| 11 GHz |

11 GHz |

| –15 |

–15 |

|

|

|

|

| 0 |

0 |

| (a) θ = 20 |

(b) θ = 40

|

0

–30

–35

and therefore no means to produce any beam squint. Therefore, the

amount of

|

15 |

beam squint must be a function of angle, θ, as well as the frequency

variation.

|

f0 |

1.1 |

|

10 |

|

|

beam direction deviation, beam squint, can be calculated as

|

| –10 |

| –15 |

|

|

Figure 6. Beam squint vs. beam angle for several frequency

deviations.

Beam Squint Considerations

The beam squint, deviation in steering angle vs. frequency, is caused

by approxi-mating a time delay with a phase shift. Implementing beam

steering with true time delay units does not have this problem.

shifter over a time delay unit? Typically, this comes down to design

simplicity and IC availability of phase shifters vs. time delays. Time

delays are implemented in some form of transmission line and the total

delay needed is a function of the aperture size. To date, most available

analog beamforming ICs are phase shift based, but there are families of

true time delay ICs emerging and these may become much more common for

phased array implementations.

digital beamforming algorithms. Therefore, a phased array

architecture where Artech House, 2005.

every element is digitized would lend itself naturally to overcome

the beam squint problem, while also providing the most programmable

flexibility. However, the power, size, and cost of such a solution can

be problematic.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

For regional headquarters, sales, and distributors or |

|

|

|

|

|

|