Including the index and logarithm laws

Exponential

and logarithmic functions

Illustrations and web design: Catherine Tan, Michael Shaw

Full bibliographic details are available from Education Services Australia.

Supporting Australian Mathematics Project

Australian Mathematical Sciences Institute

Building 161

The University of Melbourne

VIC 3010

Email: enquiries@amsi.org.au

Website: www.amsi.org.au

Two approaches . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6

Content . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 7

Derivatives of general logarithmic functions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 16

Antiderivatives of exponential and logarithmic functions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 17

A series for ex. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 29

Derangements and e . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 29

Appendix . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 36

Is e rational? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 36

The content of the modules:

• Functions II

Motivation

The greatest shortcoming of the human race is our inability to understand the exponential function.

A guide for teachers – Years 11 and 12 • {5}

involved in such repeated multiplication — namely, exponential functions such as 10x— is a useful step towards a grasp of these enormities.

In particular, we can ask questions like: How fast does an exponential function grow? It grows rapidly! But, with calculus, we can give a more precise answer.

A brief refresher

| a0= 1 | a |

|

n� |

|

|---|

Two approaches

In this module, we will introduce two new functions exand loge x. We will do this in two different ways.

A guide for teachers – Years 11 and 12 • {7}

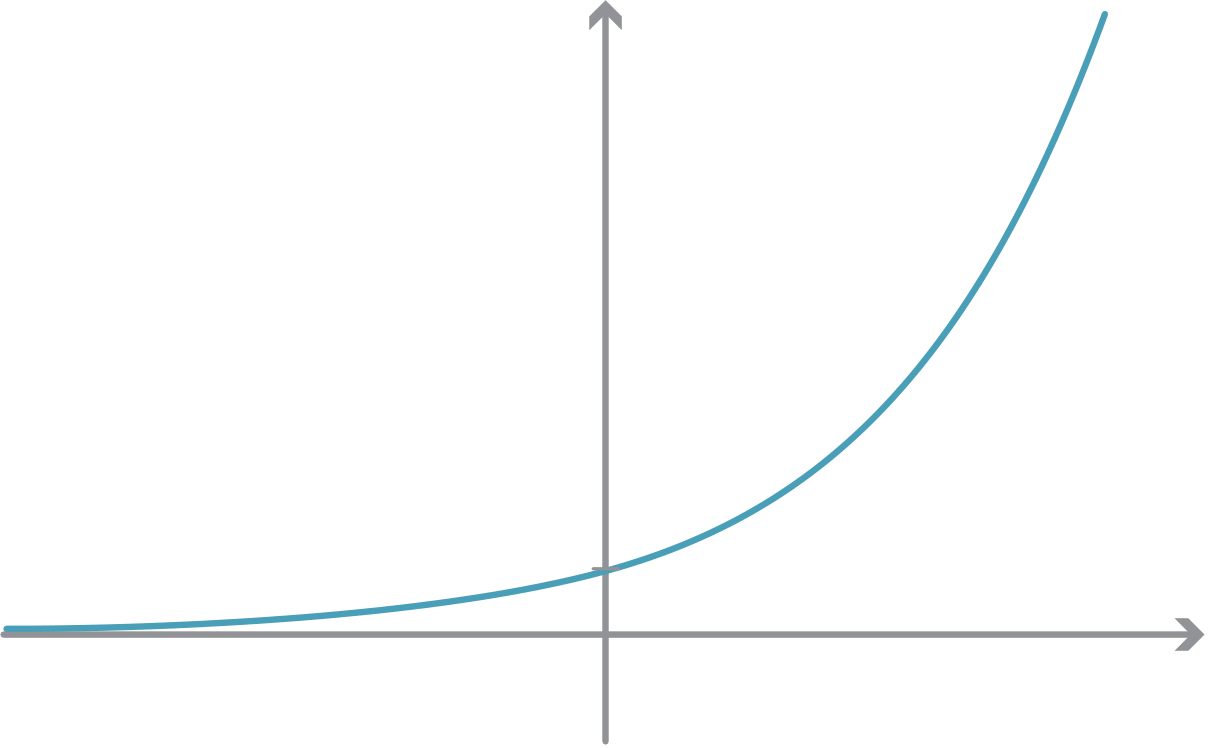

We begin by attempting to find the derivative of f (x) = 2x, which is graphed as follows.

y

The graph of y = 2xis always sloping upwards and convex down. For large negative x, it is very flat but sloping upwards. As x increases, the graph slopes increasingly upwards; as x increases past 0, the gradient rapidly increases and the graph becomes close to vertical.

Therefore, we expect f′(x) to be:

{8} • Exponential and logarithmic functions

In other words, we expect f′(x) to behave just like ... an exponential function. (We will see eventually that f′(x) = loge 2·2x.)

Let’s first attempt to compute f′(0) from first principles:

| f (h)− f (0) h |

||

|---|---|---|

| 2h−1 h | ||

Approximating f′(0) for the function f (x) = 2x

| f′(0) = lim h→0 | 2h−1 h |

|---|

Let us press on and attempt to compute f′(x) for x in general:

expectations. (We will see later that this constant is loge 2.)

The derivative of ax

| f′(0) = lim h→0 | f (h)− f (0) h | f′(x) = lim h→0 | f (x +h)− f (x) h | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| = lim h→0 | ah−1 h | = lim h→0 | ax+h− ax h |

|||

| = ax· lim h→0 | ah−1 h | |||||

f′(x) = ax· lim h→0 ah−1 h

= f′(0)· ax.

We have already found that, when a = 2, the limit is approximately 0.693147. We can do the same calculations for other values of a, and find the approximate limit. We obtain

the following table.

| a | ah−1 h | (to 6 decimal places) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | |||

| 2 |

|

||

| 3 |

|

||

| 4 | |||

| 5 |

Exercise 1

Show that, if 1 ≤ a < b and h > 0, then

| ah−1 h | ≤ lim h→0 | bh−1 h |

|---|

Geometrically, this means that, as a increases, the graph of y = axbecomes more sharply

vertical, and the gradient of the graph at x = 0 increases.

| 0 | x |

|---|

A guide for teachers – Years 11 and 12 • {11}

When a = 2, we have a gradient at x = 0 of 0.69315. When a = 3, we have a gradient of 1.0986. So we expect that there is a single value of a, between 2 and 3, for which the

The function f (x) = exis often called the exponential function, and sometimes written as expx.

Note. This approach may appear to be a sleight of hand. We didn’t really ‘prove’ that the

• We considered the derivative of f (x) = 2xand found that

f′(x) = 2x· lim h→0 2h−1 h

| • | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| f′(x) = ax· lim h→0 | ah−1 h | ||

so f′(x) is a constant multiple of f (x).

{12} • Exponential and logarithmic functions

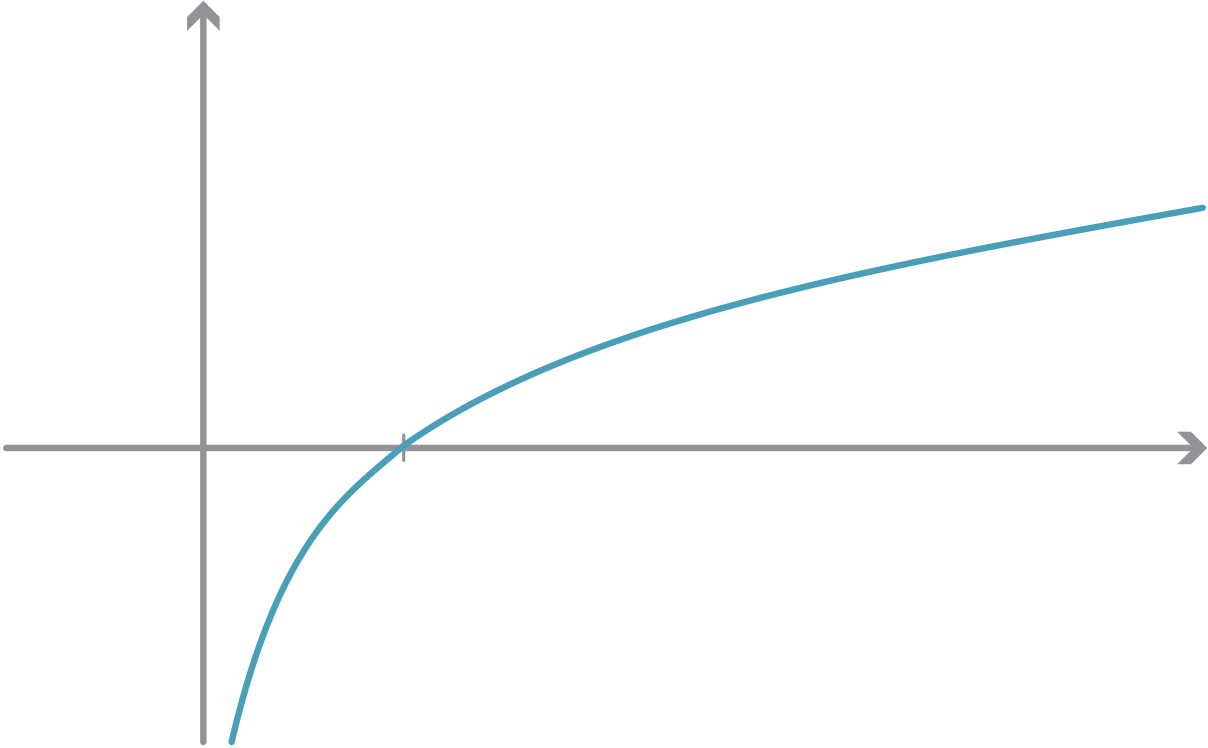

y = loge x ⇐⇒ x = ey.

The alternative notation lnx (pronounced ‘ell-en’ x) is often used instead of loge x.

| 0 | x |

|---|

A guide for teachers – Years 11 and 12 • {13}

Since we know how to differentiate the exponential, we can now also differentiate the

the equation

x = eloge x.

In general, for any real constants a and b with a ̸= 0, we can consider the function

only for x > 0; its domain is (0,∞). Yet the function 1 xis defined for all x ̸= 0, including

all negative x. Strictly speaking, the derivative of loge x is the function 1 x, restricted to the

{14} • Exponential and logarithmic functions

Exercise 4

f (x) = loge |x| =loge x

loge(−x)

y = loge(–x) y = logex

| –1 | 0 |

|

x |

|---|

The derivative of 2x, revisited

We now obtain a simple answer to our original question.

Previously we found that f′(x) ≈ 0.693147·2x. We now see that the constant is loge 2.

Exercise 6

| Exercise 7 |

|---|

f′(x) = k ekx.

We saw in the previous section, when differentiating 2x, that it can be written as eloge 2·x, which is of the form ekx. The same technique can be used to differentiate any function ax, where a is a positive real number. A function axis just a function of the form ekxin

{16} • Exponential and logarithmic functions

Exercise 8

| ah−1 h |

|---|

|

|---|

Derivatives of general logarithmic functions

Consider a logarithmic function f (x) = loga x, where a > 1 is a constant. By using the

| f′(x) = |

|

|---|

a Show that f′(x) = g′(x).

b Show that f (1) = g(1).

|

and, more generally, |

|

|---|

The basic indefinite integrals are

| � |

|

and |

|---|

where c as usual is a constant of integration.

We can use these antiderivatives to evaluate definite integrals.

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|

�x

tdt = loge x.

1Exercise 12

�loge x dx.

Warning! As we mentioned previously, loge x is only defined for x > 0, while 1 xis defined

is valid only when ax + b > 0. Although it is more complicated, it is sometimes neces-

sary to consider the function loge |x|, which is defined for all x ̸= 0 and which also has derivative 1 x. The equation

A guide for teachers – Years 11 and 12 • {19}

Graphing exponential functions

• A dilation in the x-direction from the y-axis with factor k maps

(x, y) �→ (kx, y).

• The reflection in the y-axis maps

(x, y) �→ (−x, y).

The plane is reflected vertically in the horizontal axis.

• A translation in the x-direction by a units maps

If a > 0, the translation is upwards, and if a < 0, the translation is downwards.

Note that, as the x-axis is an asymptote for the graph y = ax, any graph obtained by

{20} • Exponential and logarithmic functions

|

|

|

|---|---|---|

– 3

|

can alternatively write the x-intercept of the | |

A guide for teachers – Years 11 and 12 • {21}

When 0 < a < 1, the graph y = f (x) of the function f (x) = axhas a similar shape as for the case a > 1, but now f (x) → 0 as x → ∞ and f (x) → ∞ as x → −∞.

| Graph of f (x) = | � 1 |

|---|

Exercise 15

Exercise 16

For any a > 1, the functions f (x) = axand g(x) = loga x are inverse functions, since

f (g(x)) = aloga x= x

{22} • Exponential and logarithmic functions

y

| 1 | y = x |

|---|

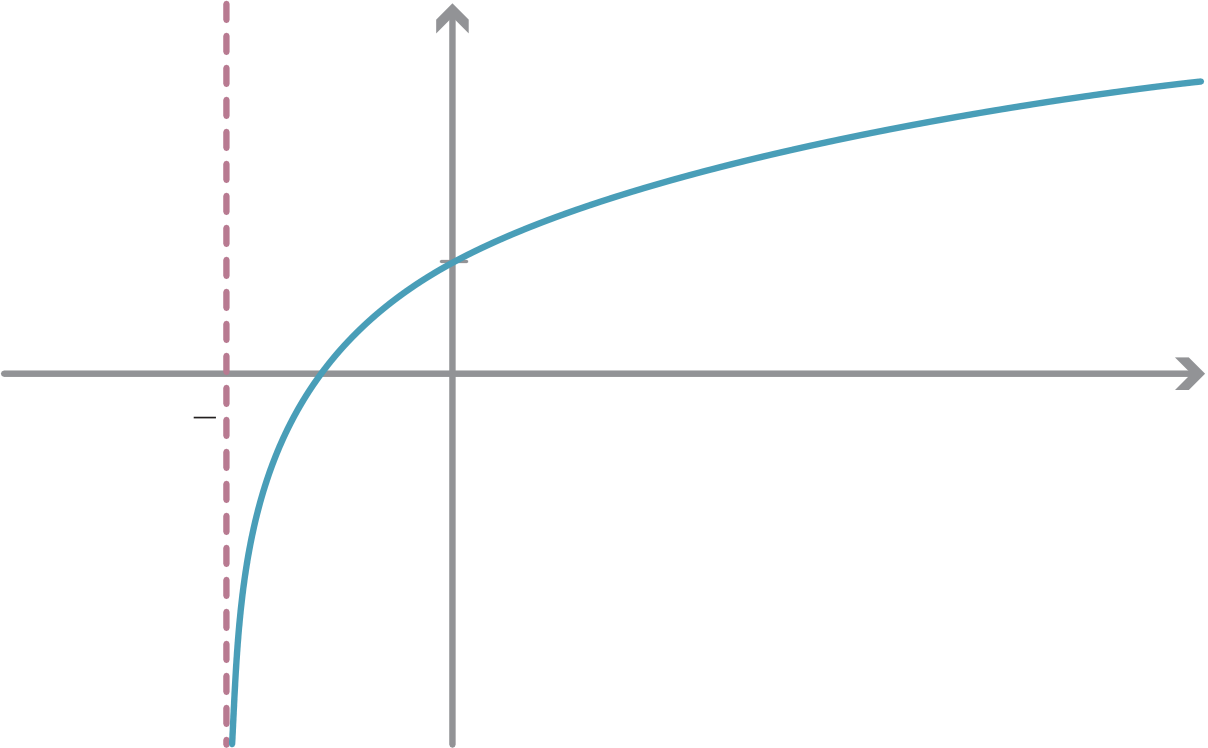

The graph of the logarithmic function loga x, for any a > 1, has the y-axis as a vertical asymptote, but has no critical points. Similarly, any other graph obtained from this graph

by dilations, reflections in the axes and translations also has a vertical asymptote and no

| d y | 1 |

|---|---|

| dx= | x loge a |

way to infinity:

loga x → ∞ as x → ∞.

number N. Does loga x ever take the value N?

That is, find x and y such that

|

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | |||

Exercise 19

Consider the graph y = log3 x. Explain why the following two transformations of the graph have the same effect:

What does an exponential mean anyway?

Throughout this module, we’ve assumed that functions like f (x) = 2xare defined for all real numbers x. But are they really?

Nor is there a problem when x is a rational number. Using the index laws again,

| 2 |

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|||

A guide for teachers – Years 11 and 12 • {25}

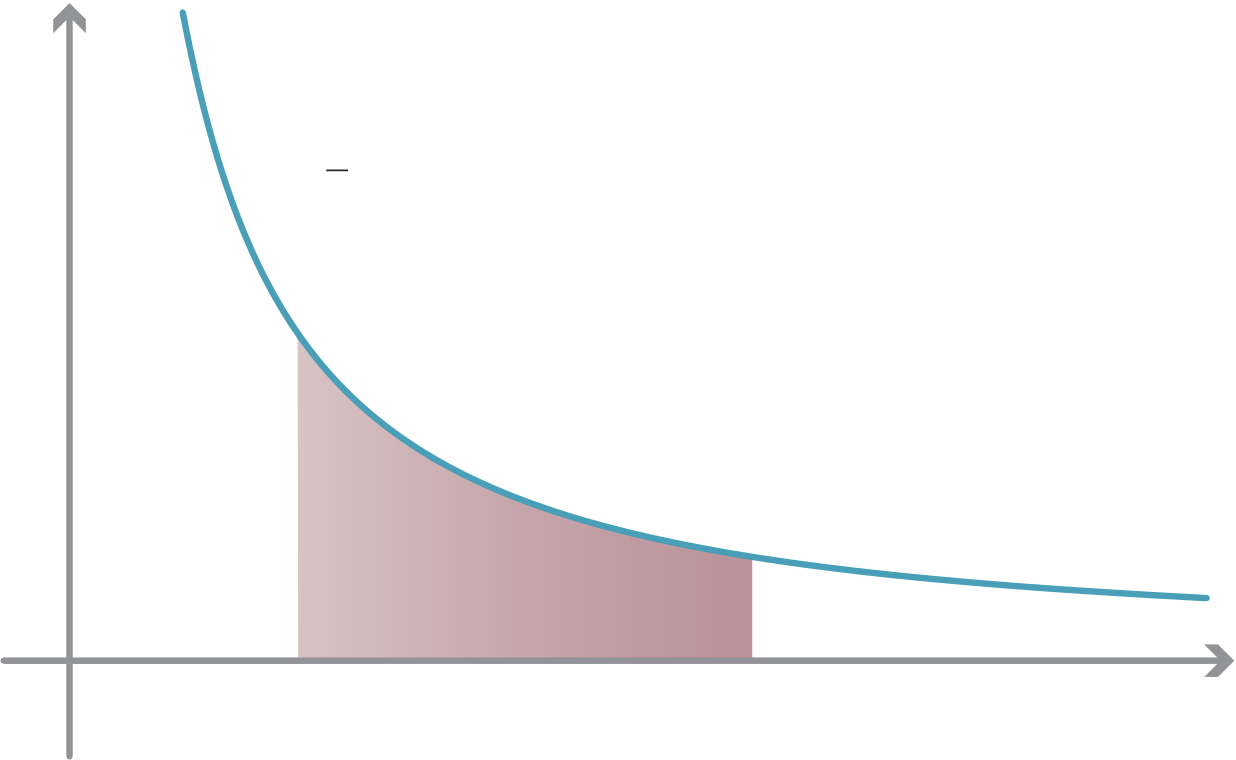

lnx =�x

tdt.

1This equation was exercise 11. It is now a definition.

| 0 | 1 | x | t |

|---|

As an aside, note the standard fact that the integral of tnis

1

n +1tn+1.From the definition, it’s not clear that the new function lnx behaves like a logarithm at all. However, we will now show directly that this new function obeys the logarithm laws. We use a similar method to exercise 10.

Take a positive number y, considered as a constant, and differentiate the two functions f (x) = ln(xy) and g(x) = lnx +ln y. We obtain

and so proves one of the logarithm laws.

Using a similar method, we can show that

| ln�x | � |

|---|

|

and |

|

|---|

Exponentials, rigorously

Having established our new version of the natural logarithm function, we now turn to

expx = ln−1(x).

We then have

We can compute the derivative of expx, since it is the inverse of lnx, and we know that

the derivative of lnx is 1 x. Let y = expx. Then x = ln y and we have

We can also show that exp satisfies the index laws. For instance, we have

Here we just used a logarithm law and the fact that ln and exp are inverses. Since the

function ln is one-to-one and we have just shown that ln

{28} • Exponential and logarithmic functions

For the remaining index law, take a rational number r; we will show exp(r x) = (expx)r.

�

,where we just used a logarithm law and the fact that ln and exp are inverses. We have

We can now use this to define irrational powers. We declare for any real number x, pos-

sibly irrational, that

�r = ar ,

and so for any real number x we can define axas follows.

Exercise 20

Let α be any real number and let f (x) = xα, for x > 0. Using the above definition for xα,

Links forward

A series for ex

| f (x) = | n=0� |

|---|

(In the n = 0 term, we set x0= 1 and follow the convention that 0! = 1.) Substituting x = 0 gives f (0) = 1. It turns out that, for any x, this series converges, and the function f is continuous and differentiable. And we can see that, if we differentiate the series term-by-term, we obtain ... the same series!

| n=0� | 1 n!. |

|---|

Suppose that a group of friends play a gift-giving game for the festive season. Let the number of friends be n. Each person writes their name down, and the names go into a hat. Each person in turn then takes a name out of the hat, until everyone has taken a name out and the hat is empty. You give a gift to the person whose name you pull out of the hat.

Of course, it won’t do to give a gift to yourself, so we hope nobody pulls out their own name! What are the chances of this happening?

also known as a permutation. If person i pulls their own name out of the hat, then f (i) = i, and i is said to be a fixed point of the permutation.

A good permutation for the purposes of gift-giving is one with no fixed points. A permu-tation with no fixed points is called a derangement. Our question is really asking what fraction of permutations are derangements.

fixed points. There are

muted in (n −2)! ways. So we add back on�n�pairs of people, and the remaining n −2 people can be per-�n�(n −2)!.

(The sign of the last term depends on n, and following the usual convention we set 0! = 1.)

|

|---|

|

|---|

Striking it lucky with e

M = min�n : X1 + X2 +···+ Xn ≥ 1�.

The number of times you expect to have to dig to obtain 1 gram of gold is the expected value E(M) of M.

Pr(M = n) = Pr(X1 +···+ Xn−1 < 1 and X1 +···+ Xn ≥ 1) = Pr(X1 +···+ Xn−1 < 1)−Pr(X1 +···+ Xn < 1).

As it turns out,4the probability that you have less than a gram after n digs is

| Pr(M = n) = |

|---|

Thus Pr(M = 1) = 0 and, for n > 1, we can simplify to

E(M) = 1Pr(M = 1)+2Pr(M = 2)+3Pr(M = 3)+4Pr(M = 4)+···

|

|---|

A guide for teachers – Years 11 and 12 • {33}

Sandwiching e

| 0 | y = |

|

n |

|

x |

|---|

= lnn +1

| = ln�1+1 | |

|---|---|

n +1≤ n ln�1+1 n |

� | = ln�1+1 | �n | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||||

| n→∞ln�1+1 | �n |

|

||||||

| n→∞lim�1+x n | �n |

|

|---|

History and applications

A guide for teachers – Years 11 and 12 • {35}

Now the bank says, it can give you a third of the interest rate, but three times as often. So, 331 3% interest is paid out three times throughout the year. Your $1000 becomes $1333.33, then $1777.78, then $2370.37 (to the nearest cent) at the end of the year. You end up with more again.

interest rate, one billion times a year!), this amount approaches none other than e:

| n→∞lim�1+1 | �n |

|---|

each year. As exercise 21 shows, this limit turns out to be ex.

Although some of the above ideas were discussed by Bernoulli, the notation e was not used until much later. Its first known appearance is in a letter of Euler from 1731.

It turns out that e is irrational. We can give a proof of this fact.

Suppose to the contrary that e can be written as a fraction, so

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

�1+1 1!+ 1 2!+···+ 1 b! | � | + | � | |||

| (b −1)!a = | �b!+b! 1!+···+ b! | � | + | � |

|

|

|---|

Therefore, the sum x of the terms in the second bracket must be a positive integer.

However, all the terms in the second bracket are rather small. The denominators (b +1), (b + 1)(b + 2), (b + 1)(b + 2)(b + 3) increase very quickly. So x is a small positive integer ... suspiciously small. Noting that (b +1)(b +2)···(b +k) > (b +1)k, for all k ≥ 2, we can estimate x as

| 1 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| = | b +1· b +1 |

So x is a positive integer with x <1 b≤ 1. There are not many positive integers less than one! This is a contradiction, and so our initial assumption must have been wrong. We conclude that e is irrational.

In fact, it can be shown that, like π, the number e is transcendental: it is not the root of any polynomial with rational coefficients.

|

|---|

Exercise 4

Exercise 5

The function f (x) is defined when

3−7x > 0, i.e., x <3 7. So the

domain is (−∞, 3 7).

| f′(0) = lim h→0 | 2h−1 h |

|

|---|

We have now shown that f′(x) = loge 2·2x, so f′(0) = loge 2. The desired equality follows.

|

||

|---|---|---|

| = xx� | x ·1 x+1·loge x | |

Exercise 10

| f′(x) | 1 | |

|---|---|---|

| = | loge a·xy· = | x loge a |

Hence f′(x) = g′(x).

b Since loga 1 = 0, we compute f (1) = loga y and g(1) = loga y.

| �x | �loge t | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|||

Exercise 12

f′(x) = 1·loge x + x ·1 x−1 = loge x.

Thus f (x) is an antiderivative of loge x, and we have �loge x dx = x loge x − x +c,

Substituting x = 0 gives a y-intercept of 5 − 4 · 3 = −7. Substituting y = 0, we obtain

0 = 5−4·32x+1, and so 32x+1=5 4. Hence the x-intercept is

1 2(log3 5

• dilation by a factor of1 2in the x-direction from the y-axis, giving y = e2x

• dilation by a factor of 4 in the y-direction from the x-axis, giving y = 4e2x

y

|

5 (log3 – 1) |

x | |

|---|---|---|---|

Exercise 15

A guide for teachers – Years 11 and 12 • {41}

Under these transformations, the asymptote moves to y = 3.

| –log2 3 – 1 | 2 |

x | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 |

Exercise 16

Subtracting the first equation from the second gives loge(x + 106) − loge x = 1. Using a logarithm law, this simplifies to

log3�x�= log3 x −log3 9 = log3 x −2,

so these two graphs are identical.

f′(x) =α xexp(α lnx) = α x· xα = αxα−1.

Note. In the final step of the calculation above, we used an index law. We first need to

1

We can compute this exactly as

| �n+x | |||

|---|---|---|---|

= lnn + x

x |

� |

|

|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

|

|---|