Historical evolution of the cluster; cluster performance; current and trends overtime

Table of Contents

THE GLOBAL MARKET FOR WATCHES 3

The Swiss Watch Cluster Diamond 6

The precision engineering cluster and fashion clusters support the watch cluster through skill transfers 8

The other Swiss industries support the high-quality image of the “Swiss Brand” 8

INTRODUCTION

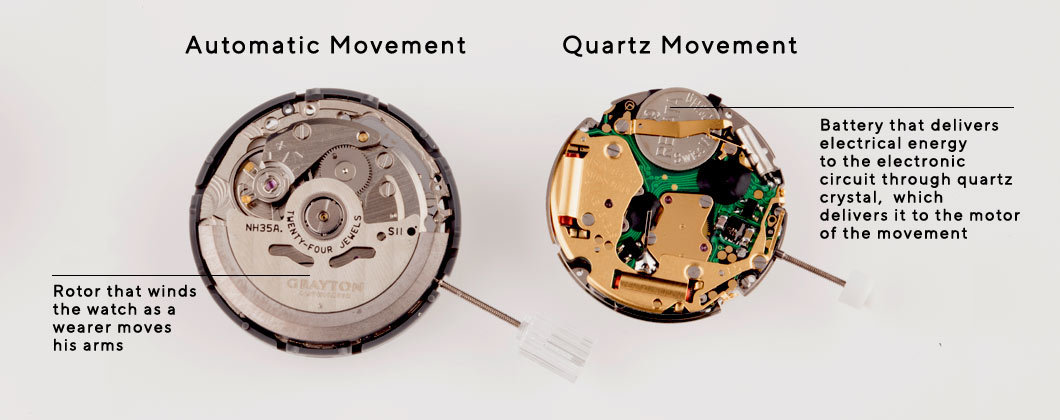

There is two class of class when it comes to wristwatch they are mechanical and Quartz. A mechanical watch is relying on the unwinding spring and mechanical “movements” to pace hands accurately around a dial. Whereas quartz watches work on battery power and they use quartz oscillators so that they can keep their time accurately.

In

recent times quartz watches have become a popular product worldwide

because they have become cheaper to produce and they are also more

accurate. Mechanical watches are mostly used in the luxury segment, but

then quartz watches do exit. The most important determinant which adds

on the watch is the values to the country in which they are

originated.

In

recent times quartz watches have become a popular product worldwide

because they have become cheaper to produce and they are also more

accurate. Mechanical watches are mostly used in the luxury segment, but

then quartz watches do exit. The most important determinant which adds

on the watch is the values to the country in which they are

originated.

THE GLOBAL MARKET FOR WATCHES

MAPPING OF THE CLUSTER

The cluster map is shown above which can be described as wide. It includes the manufacture and also highlights the company watch cluster from the core. The local supplies can be seen on the left which includes engineering services, machinery, metal, and equipment tools. The competitiveness of the suppliers can be termed as high and they are also similar to other industries that are linked to parts of manufacturing, which are equipped with the highly skilled workforce which includes MDS (medical devices), information technology, and ABB (nanotechnology). On the right side of the map, it highlights suppliers of a firm that includes local communication, designers, advertising agencies and they also have specialized banks (Auer and Saure, 2011). This portion can be defined as less competitive when we consider the foreign brand (LVHM) to carry out all the activities, where the production was kept in Switzerland. The related industry includes Jewelry and some Swiss luxury goods group. Top of the map highlights the educational organization which plays a crucial role in bringing the skilled labor in the cluster, earlier this role was fulfilled by the institution of collaboration. At the bottom of the map, it highlights the federal government and cantonal Government which deals with all the regulation (these are Swiss-made rules), and they also fund some of the educational institutes as well (Auer and Saure, 2011).

HISTORICAL EVOLUTION OF THE CLUSTER; CLUSTER PERFORMANCE; CURRENT AND TRENDS OVERTIME

The Asian/Quartz crisis: 1970-1983: Switzerland came out to be the dominant watch manufacturer over a century ago. However, the innovation of quartz technology in the early 1970s presented a revolution that forced the Swiss watchmaking cluster into a crucial crisis. Quartz wristwatches were first developed by the Centre Electronique Horloge(CEH) in Switzerland, Neuchâtel in 1967. The Swiss watchmakers were unwilling to change their traditional production methods to produce low priced quartz watches on a large scale. To produce Quartz watches it requires the electronics and operations expertise of the Japanese to commercialize quartz watches (Piguet, 2008). With the introduction of quartz technology, there was a decline in the price for watches, as Seiko and other Japanese companies were able to tamper production improvements and economies of scale. By 1980, Switzerland lost most of its share in the market to Citizen and Seiko. This also led to a reduction of employment in the Swiss watch industry over the period of the Quartz crisis.

PERFORMANCE OF THE CLUSTER

CLUSTER COMPETITIVENESS; CLUSTER-SPECIFIC BUSINESS ENVIRONMENT, KEY COMPANIES, EXTENT OF COLLABORATION, NATURE, AND IMPACT OF CLUSTER SPECIFIC GOVERNMENT POLICIES

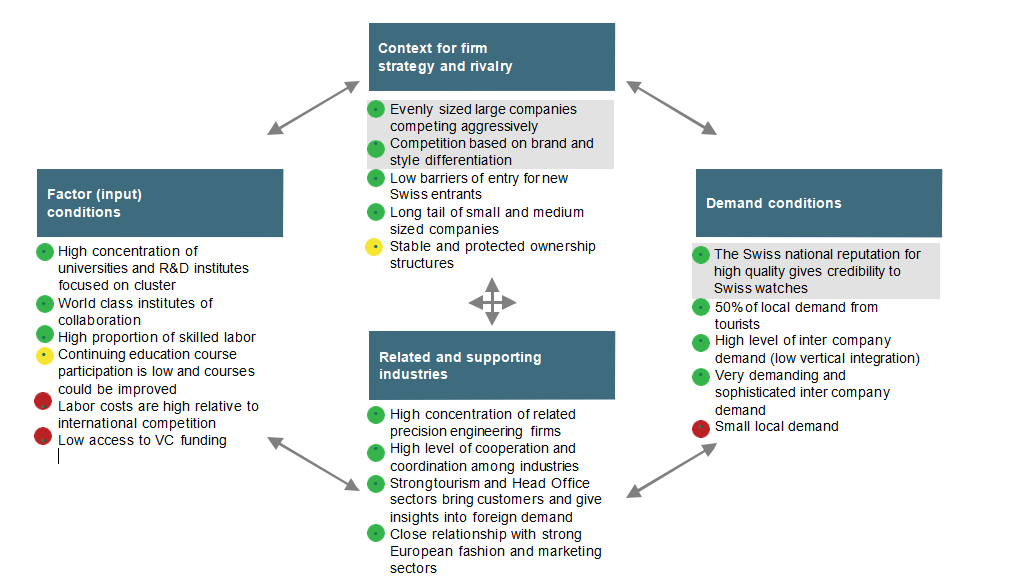

The Swiss Watch Cluster Diamond

Factor (Input) Conditions

Strong IFCs – The Swiss cluster is also supported by a strong group of IFCs and scientific research organizations working on the general microtechnology and watchmaking specific ones. The Jura Canton located at the center is not only of the watchmaking cluster but also the growing cluster of precision engineering cluster and microtechnology. The innovation aspect of the cluster is it have typically long-time frames, capital intensive, and is not easy to patent. Thus, the incentive to innovate is low for the companies and IFCs, and thus the other research bodies are important. To overcome this need, many scientific instructions have been developed around the cluster focusing on the R&D projects. The Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Lausanne (EPFL), The Institute of Mirco-technology at the University of Neuchâtel (IMT) and Swiss Centre for Electronics and Micro-technology (CSEM) are the major organizations, EPEL and IMT are focusing on the early R&D while CSEM focuses on the interface between research and industry, these organizations perform both research functions and also cluster coordination functions. Recently, the cluster has rearranged other IFCs which focus on marketing which deals with market research, government lobbying, and other general co-ordination issues of the cluster. Till date, the most important IFC is the Federation of Swiss Watch Industry (FH) which was formed in the year 1930 due to the decline caused by the great depression. This IFC plays an important role in coordinating information sharing, promoting the Swiss watch industry and marketing globally, and recently the main function of this IFC is as a monitor to the government to protect regulation around the Swiss brand industry. In addition to these IFC, a large number of industry trade journals and magazines are present which facilitates information sharing and serves as publication material for the cluster firms. Currently, there are 20 unique journals and magazines which are present in Switzerland.

Related and supporting industries

Another key element that enables the Switzerland watch cluster for success is the structure of the industry, and the way the Swiss firms complete one another. It is observed that the industry is highly consolidated with 5 conglomerates generating 53% of the total retail value of watches. But this creates aggressive competition as all the four large firms are equally sized (Tora and Nolan, 2006). Also, the firm chose to compete on the basis of brand proliferation and innovation in product marketing and design (UTTINGER and PAPERA, 1965). This allows them to successfully capitalize on the unique demands and maintain the price (Tora and Nolan, 2006). In today's era, there are a large number of Swiss watch brands that concentrate on high-end mechanical watches. This indicates their capability to complete thorough the continual re-launch of brands than completing through price (UTTINGER and PAPERA, 1965).

KEY COMPETITIVENESS ISSUES FACING THE CLUSTER

Though, the Swiss watch cluster is very strong still it must work in order to maintain its status. The major risk of the cluster can be concluded by the internal factors that are incentivizing Swiss watchmakers to change their way of completing and thus lead to devaluing the Swiss brand, there also exist external risks which are related to the high value-added activities like design and marketing migrating to other areas. Other risks arise from the strength and sophistication of the Asian demand which results in the risk of a rise in foreign luxury watchmakers (UTTINGER and PAPERA, 1965).

POLICY RECOMMENDATIONS

REFERENCES

Auer, R., and Saure, P., 2011. Export Basket and the Effects of Exchange Rates on Exports—Why Switzerland Is Special. Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas, Globalization and Monetary Policy Institute Working Papers, 2011(77).

Feld, L., Kirchgässner, G. and Schaltegger, C., 2010. Decentralized Taxation and the Size of Government: Evidence from Swiss State and Local Governments. Southern Economic Journal, 77(1), pp.27-48.

Tora, S. and Nolan, C., 2006. Industrial Clusters and Inter-Firm Networks - Edited by Charlie Karlsson, Börje Johansson and Roger R. Stough. Papers in Regional Science, 85(4), pp.617-619.

UTTINGER, H. and PAPERA, D., 1965. THREATS TO THE SWISS WATCH CARTEL. Economic Inquiry, 3(2), pp.200-216.