Germany hall and eibe frank department computer science

Logistic Model Trees†

Niels Landwehr

Institute for Computer Science, University of Freiburg, Freiburg, Germany.Abstract. Tree induction methods and linear models are popular techniques for supervised learning tasks, both for the prediction of nominal classes and numeric values. For predicting numeric quantities, there has been work on combining these two schemes into ‘model trees’, i.e. trees that contain linear regression functions at the leaves. In this paper, we present an algorithm that adapts this idea for classification problems, using logistic regression instead of linear regression. We use a stagewise fitting process to construct the logistic regression models that can select relevant attributes in the data in a natural way, and show how this approach can be used to build the logistic regression models at the leaves by incrementally refining those constructed at higher levels in the tree. We compare the performance of our algorithm to several other state-of-the-art learning schemes on 36 benchmark UCI datasets, and show that it produces accurate and compact classifiers.

Keywords: Model tree, logistic regression, classification

2 Landwehr, Hall and Frank

1. Introduction

paper.tex; 9/02/2006; 14:21; p.2

Logistic Model Trees 3

2.1. Tree Induction

The goal of supervised learning is to find a subdivision of the instance space into regions labeled with one of the target classes. Top-down tree induction finds this subdivision by recursively splitting the instance space, stopping when the regions of the subdivision are reasonably‘pure’ in the sense that they contain examples with mostly identical class labels. The regions are labeled with the majority class of the examples in that region.

paper.tex; 9/02/2006; 14:21; p.3

4 Landwehr, Hall and Frank

|

|---|

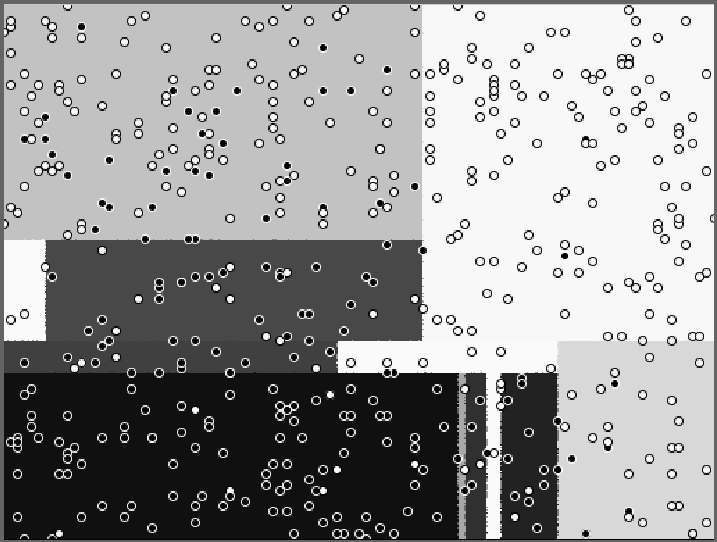

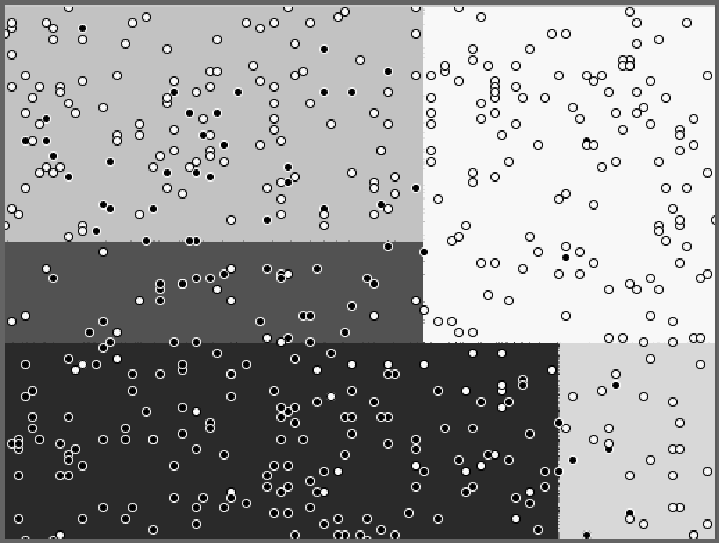

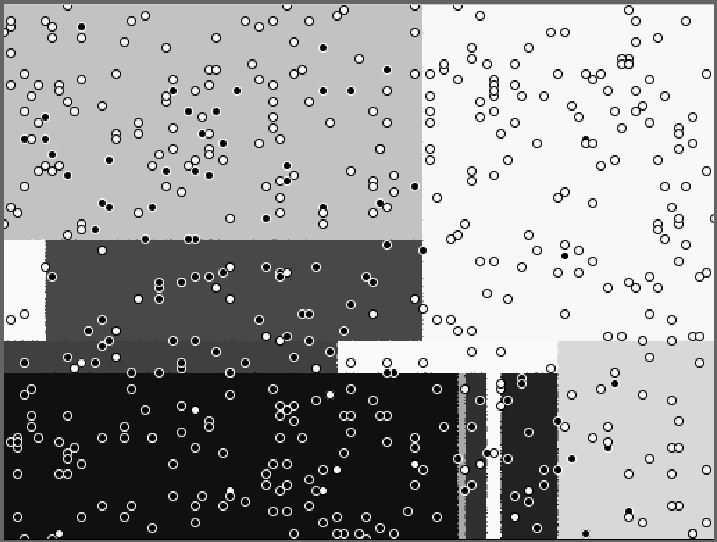

Figure 2. Subdivisions of increasing complexity for the ‘polynomial-noise’ dataset,

Figure 2 shows three subdivision of the R2instance space for the‘polynomial-noise’ dataset, generated by a decision stump learner (i.e. a one-level decision tree), C4.5 (Quinlan, 1993) with the ‘minimum in-stances’ parameter set to 20, and C4.5 with standard options. They are increasingly more complex; in this case, the center one would probably be adequate, while the rightmost one clearly overfits the examples.

The usual approach to the problem of finding the best number of splits is to first perform many splits (build a large tree) and afterwards use a ‘pruning’ scheme to undo some of these splits. Different pruning schemes have been proposed. For example, C4.5 uses a statistically motivated estimate for the true error given the error on the training data, while the CART (Breiman et al., 1984) method cross-validates a‘cost-complexity’ parameter that assigns a penalty to large trees.

Assume we have a class variable G that takes on values 1, . . . , J. The idea is to transform this class variable into J numeric ‘indicator’variables G1, . . . , GJ to which the regression learner can be fit. The indicator variable Gj for class j takes on value 1 whenever class j is present and value 0 everywhere else. A separate model is then fit to every indicator variable Gj using the regression learner. When classi-fying an unseen instance, predictions u1, . . . , uJ are obtained from the numeric estimators fit to the class indicator variables, and the predicted class is

|

|---|

where x is the vector of attribute values for the instance (we assume a constant component in the input vector to accommodate the intercept).

The model is fit to minimize the squared error:

| β∗= argmin | n | |

|---|---|---|

| β | i=1 |

6 Landwehr, Hall and Frank

2.3. Logistic Regression

Pr(G = J|X = x) = βT jx,

or, equivalently,

Fitting a logistic regression model means estimating the parameter vectors βj. The standard procedure in statistics is to look for the maximum likelihood estimate: choose the parameters that maximize the probability of the observed data points. For the logistic regression model, there are no closed-form solutions for these estimates. Instead, we have to use numeric optimization algorithms that approach the maximum likelihood solution iteratively and reach it in the limit.

In a recent paper that links boosting algorithms like AdaBoost to additive modeling in statistics, Friedman et al. propose the LogitBoost algorithm for fitting additive logistic regression models by maximum

1. Start with weights wij = 1/n, i = 1, . . . , n, j = 1, . . . , J, Fj(x) = 0

and pj(x) = 1/J ∀j

| zij = |

|

|---|

wij = pj(xi)(1 −pj(xi))

3. Output the classifier argmax Fj(x)

j

M

where Fj(x) = fmj(x) and the fmj are (not necessarily linear) m=1

functions of the input variables. Indeed, the authors show that if re-gression trees are used as the fmj, the resulting algorithm has strong connections to boosting decision trees with algorithms like AdaBoost.ij Figure 3 gives the pseudocode for the algorithm. The variables y∗encode the observed class membership probabilities for instance xi, i.e.

8 Landwehr, Hall and Frank

LogitBoost performs forward stagewise fitting: in every iteration, it computes ‘response variables’ zij that encode the error of the currently fit model on the training examples (in terms of probability estimates), and then tries to improve the model by adding a function fmj to the committee Fj, fit to the response by least-squared error. As shown in (Friedman et al., 2000), this amounts to performing a quasi-Newton step in every iteration, where the Hessian matrix is approximated by its diagonal.

paper.tex; 9/02/2006; 14:21; p.8

Logistic Model Trees 9

1 We take the number of classes J as a constant here, otherwise there is another

factor of J.

2.3.2. Handling Nominal Attributes and Missing Values

In real-world domains important information is often carried by nomi-nal attributes whose values are not necessarily ordered in any way and thus cannot be treated as numeric (for example, the make of a car in the ‘autos’ dataset from the UCI repository). However, the regression functions used in the LogitBoost algorithm can only be fit to numeric attributes, so we have to convert those attributes to numeric ones. We followed the standard approach for doing this: a nominal attribute with k values is converted into k numeric indicator attributes, where the l-th indicator attribute takes on value 1 whenever the original attribute takes on its l-th value and value 0 everywhere else. Note that a dis-advantage of this approach is that it can lead to a high number of attributes presented to the logistic regression if the original attributes each have a high number of distinct values. It is well-known that a high dimensionality of the input data (in relation to the number of training examples) increases the danger of overfitting. On such datasets, at-tribute selection techniques like the one implemented in SimpleLogistic will be particularly important.Another problem with real-world datasets is that they often contain missing values, i.e. instances for which not all attribute values are ob-served. For example, an instance could describe a patient and attributes correspond to results of medical tests. For a particular patient results might only be available for a subset of all tests. Missing values can occur both during training and when predicting the class of an unseen instance. The regression functions that have to be fit in an iteration of

3. Related Tree-Based Learning Schemes

Starting from simple decision trees, several advanced tree-based learn-ing schemes have been developed. In this section we will describe some of the methods related to logistic model trees, to show what our work builds on and where we improve on previous solutions. Some of the related methods will also be used as benchmarks in our experimental study, described in Section 5.

paper.tex; 9/02/2006; 14:21; p.11

12 Landwehr, Hall and Frank

In this section, we will briefly discuss a different algorithm for induc-ing (numeric) model trees called ‘Stepwise Model Tree Induction’ or SMOTI (Malerba et al., 2002) that builds on an earlier system called TSIR (Lubinsky, 1994). Although we are more concerned with clas-sification problems, SMOTI uses a scheme for constructing the linear regression functions associated with the leaves of the model tree that is related to the way our method builds the logistic regression functions at the leaves of a logistic model tree. The idea is to construct the final multiple regression function at a leaf from simple regression functions that are fit at different levels in the tree, from the root down to that particular leaf. This means that the final regression function takes into account ‘global’ effects of some of the variables—effects that were not inferred from the examples at that leaf but from some superset of examples found on the path to the root of the tree. An advantage of this technique is that only simple linear regressions have to be fitted at the nodes of the tree, which is faster than fitting a multiple regres-sion every time (that has to estimate the global influences again and again at the different nodes). The global effects should also smooth the predictions because there will be less extreme discontinuities between the linear functions at adjacent leaves if some of their coefficients have been estimated from the same (super)set of examples.

paper.tex; 9/02/2006; 14:21; p.12

After the initial tree is grown, it is pruned back using a pruning method similar to the one employed in the CART algorithm (Breiman et al., 1984). The idea is to use a ‘cost-complexity measure’ that com-bines the error of the tree on the training data with a penalty term for the model complexity, as measured by the number of terminal nodes. The cost-complexity-measure in CART is based on the misclassification error of a (sub)tree, whereas in Lotus it is based on the deviance. The deviance of a set of instances M is defined as

deviance = −2 · logP(M|T)

where P(M|T) denotes the probability of the data M as a function of the current model T (which is the tree being constructed).

The algorithm uses a standard top-down recursive partitioning strat-egy to construct a decision tree. Splitting at each node is univariate, but considers both the original attributes in the data and new attributes constructed using an attribute constructor function: multiple linear regression in the regression setting and linear discriminants or multiple logistic regression in the classification setting. The value of each new attribute is the prediction of the constructor function for each example that reaches the node. In the classification case, one new attribute is created for each class and the values are predicted probabilities. In the regression case, a single new attribute is created. In this way the algo-rithm considers oblique splits based on combinations of attributes in addition to standard axis-parallel splits based on the original attributes. For split point selection, information gain is used in the classification case and variance reduction in the regression case.

Once a tree has been grown, it is pruned back using a bottom-up procedure. At each non-leaf node three possibilities are considered: performing no pruning (i.e, leaving the subtree rooted at the node in place), replacing the node with a leaf that predicts a constant, or replacing it with a leaf that predicts the value of the constructor function that was learned at the node during tree construction. C4.5’s error-based criterion (Quinlan, 1993) is used to make the decision.

Logistic Model Trees 15

Although a variety of boosting algorithms have been developed, we will here concentrate on the popular AdaBoost.M1 algorithm (Freund and Schapire, 1996). The algorithm starts with equal weights assigned to all instances in the training set. One weak classifier (for, example, a C4.5 decision tree) is built and the data is reweighted such that correctly classified instances receive a lower weight: their weights are updated by

ewhere e is the weighted error of the classifier on the current data. In a weight ←weight ·1 −e

Boosting trees has received a lot of attention, and has been shown to outperform simple classification trees on many real-world domains. In

paper.tex; 9/02/2006; 14:21; p.15

4.1. The Model

A logistic model tree basically consists of a standard decision tree struc-ture with logistic regression functions at the leaves, much like a model tree is a regression tree with regression functions at the leaves. As in ordinary decision trees, a test on one of the attributes is associated with every inner node. For a nominal (enumerated) attribute with k values, the node has k child nodes, and instances are sorted down one of the k branches depending on their value of the attribute. For numeric attributes, the node has two child nodes and the test consists of comparing the attribute value to a threshold: an instance is sorted down the left branch if its value for that attribute is smaller than the threshold and sorted down the right branch otherwise.

S = St, St ∩St′ = ∅for t ̸= t′

t∈TUnlike ordinary decision trees, the leaves t ∈T have an associated logistic regression function ft instead of just a class label. The regres-sion function ft takes into account a subset Vt ⊆V of all attributes present in the data (where we assume that nominal attributes have been binarized for the purpose of regression), and models the class membership probabilities as

if αj model tree is then given by vk= 0 for vk/∈Vt. The model represented by the whole logistic

f(x) = ft(x) · I(x ∈St)

t∈T

18 Landwehr, Hall and Frank

the subsets encountered at lower levels in the tree become smaller and smaller, it can be preferable at some point to build a linear logistic model instead of calling the tree growing procedure recursively. This is one motivation for the logistic model tree algorithm.

Figure 4 visualizes the class probability estimates of a logistic model tree and a C4.5 decision tree for the ‘polynomial-noise’ dataset in-troduced in Section 2.1. The logistic model tree initially divides the instance space into 3 regions and uses logistic regression functions to build the (sub)models within the regions, while the C4.5 tree partitions the instance space into 12 regions. It is evident that the tree built by C4.5 overfits some patterns in the training data, especially in the lower-right region of the instance space.

The entire left subtree of the root of the ‘original’ C4.5 tree has been replaced in the logistic model tree by the linear model with

F1(x) = −0.39 + 5.84 · x1 + 4.88 · x2

F2(x) = 0.39 −5.84 · x1 −4.88 · x2 = −F1(x)

Note that this logistic regression function models a similar influence of the attributes x1, x2 on the class variable as the subtree it replaced, if we follow the respective paths in the tree we will see it mostly predicts

<= -0.13 > -0.13

x1 x1

<= 0.14 > 0.14 <= -0.03 > -0.03 <= -0.44 > -0.44

2 (112.0/8.0) x1 2 (20.0/5.0) 1 (6.0) 1 (3.0) 2 (39.0/11.0)

<= 0.15 > 0.15

1 (3.0/1.0) 2 (5.0/1.0)

| F1(x) = |

|

x1 | <= −0.13 | . | > −0.13 |

|

> 0.09 | 0.31 | . | x1 x1 | + | 2.62 | . | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| + 4.88.−4.88. | x1 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| F2(x) = | x1 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| F1(x) = | − | 0.48 | − | 0.93 | . | x1 x1 | + | 5.52 | 3.54 | + | ||||||||||||

| F2(x) = | 0.48 | + | 0.93 | . | − | 5.52 | . |

|

− | 3.54 | − | 0.31 | . | − | 2.62 | . |

|

|||||

class one if x1 and x2 are both large. However, the linear model is simpler than the tree structure, and so less likely to overfit.

4.2. Building Logistic Model Trees

The LogitBoost algorithm (discussed in Section 2.3) provides a natu-ral way to do just that. Recall that it iteratively changes the linear class functions Fj(x) to improve the fit to the data by adding a simple linear regression function fmj to Fj, fit to the response variable. This means changing one of the coefficients in the linear function Fj or introducing a new variable/coefficient pair. After splitting a node we can continue running LogitBoost iterations, fitting the fmj to the response variables of the training examples at the child node only.

As an example, consider a tree with a single split at the root and two successor nodes. The root node n has training data Dn and one the logistic regression models in isolation means the model fn would of its children t has a subset of the training data Dt ⊂Dn. Fitting