Constructive model for software product quality

SOFTWARE PRODUCT QUALITY: Theory, Model, and Practice

R. Geoff. Dromey,

Software Quality Institute,

Griffith University,

Nathan, Brisbane, QLD 4111

AUSTRALIA

|

22/09/09 | 17:10 |

|---|

Software Product Quality 2

1. Introduction

Proposals for modelling software product quality have had very limited success[1-3]. We suggest there are several clear reasons for this.

Our claim is that when these matters are properly attended to it is possible to construct practical models of software product quality. Here we will employ a goal-directed requirements-design-implementation strategy to develop a model framework, or architecture for a software product quality model, and a sample instantiation of the model that seeks to attend to these matters. This approach has been taken quite deliberately for two reasons: firstly there are a number of different interest groups that have quite distinct software product quality requirements. Our model architecture will need to properly accommodate these requirements; secondly, this strategy is one that people involved with software will find easy to relate to because of its wide application in software development.

|

22/09/09 | 17:10 |

|---|

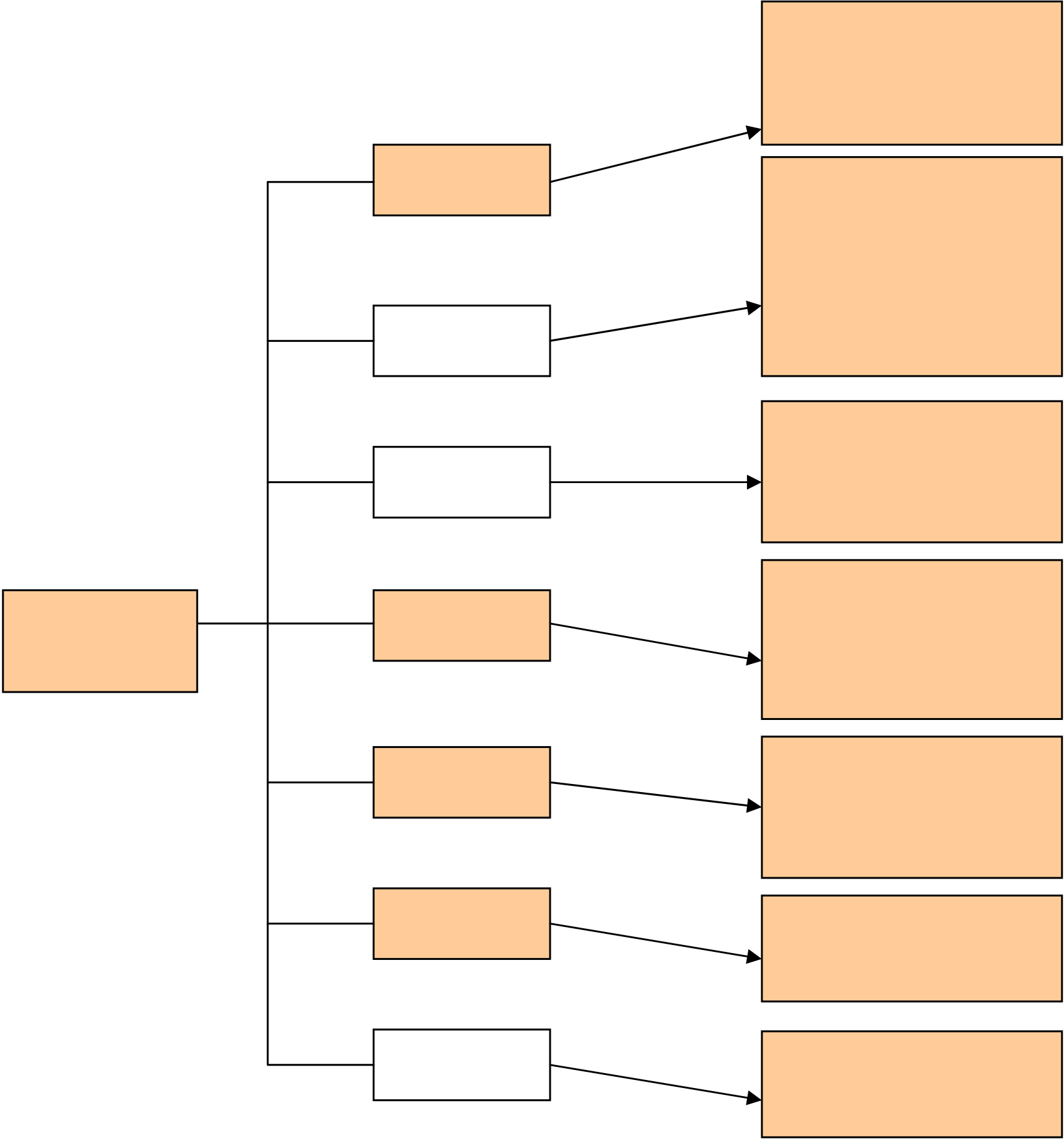

The second stage in building a model for software product quality is to identify a suitable architecture/design for such models. In summary, the following diagram encapsulates the high level architecture of the model we will propose and discuss.

Software Product Quality Model

| Product | LINKAGE | |

|---|---|---|

| Model |

|

|

|---|

| 22/09/09 | 17:10 |

|---|

2. Terminology and Framework

Before we can make serious progress with the construction of a model for software product quality we need to sort out some use of terminology. This step will allow us to establish what is often called in technical terms a universe of discourse. The advantage of doing this is that it allows us to set out how we intend to use a variety of words and how we intend to link these words to various concepts. A lot of problems arise in discussions about software product quality because there is confusion about how various terms are used.

output User-performed-function(software).

The output varies depending on the use. For the use “maintainability” the output may be a modified version of the input, whereas for the use “learnability” the output could be a set of verifiable statements that reflects the user’s understanding of the system or a set of tasks (plus time to learn) that the user knows how to perform using the software system.

| 22/09/09 | 17:10 |

|---|

To formulate the requirements for a software product quality model three issues must be addressed: the different interest groups need to be identified; the intended applications of the model need to be spelled out; and it is necessary to establish the quality needs or perspectives/views of the different interest groups.

An appropriate starting point for obtaining a set of requirements is to ask the fundamental question:

Being clear at the outset about the use or uses of a definition, a theory, or a model, can make the job of constructing that definition, model or theory a lot easier. Such an appraisal gives us a concrete goal to aim for and a set of requirements to satisfy.

We suggest that the primary applications of such a model are:

to provide a framework that can be extended to meet particular domain/application-specific quality needs,

to have a model that can be understood at a number of levels by the different interest groups involved with software,

Kitchenham and Pfleeger[3] have recently discussed Garvin’s approach in the context of software product quality. We suggest Garvin’s “model” is a useful starting point not as a quality model in its own right but rather as a specification of a set of

requirements for quality models or alternatively as a set criteria for evaluating product quality models. By this we mean that any proposed model should be rich enough to accommodate Garvin’s five perspectives if we regard them as model criteria to be satisfied. Garvin’s proposal implies that some interested party holds each of the five perspectives. It follows that in designing both quality models and quality products it is important to try to meet the needs of the different interest groups. We will revisit these issues in the discussion that follows. We will also use Garvin’s “criteria” as part of the evaluation of our proposed model and architecture.

A second important concept advanced by the Philosophy of Resemblances is the distinction between determinable and determinate characteristics. Characteristics have different degrees of determinateness. Price claims that these two adjectives are too fundamental to be defined but that their meaning can be illustrated. For example, the

|

22/09/09 | 17:10 |

|---|

We suggest that a constructive strategy can be employed to characterise the behaviours and uses of software that contribute to its quality. In constructing a model for software product quality it is appropriate to apply both bottom-up and top-down strategies. We seek to enumerate concrete properties and classify them as belonging to software characteristics and, in turn, at the next level up, we seek to enumerate software characteristics that characterise each behaviour and each use – this corresponds to bottom-up construction. We also employ derivation and/or decomposition to characterise or define abstract properties (e.g. behaviours and uses) in terms of subordinate behaviours, uses and software characteristics – this corresponds to a top-down approach. Both bottom-up and top-down construction have important roles to play in building a quality model.

We will start this discussion by considering the two principles that guide decomposition and derivation.

|

|

|---|

| 22/09/09 | 17:10 |

|---|

In adopting this principle the challenge we face is where to draw the line between subordinate defining behaviours and contributing software characteristics (note the direction of the arrows in the diagram above is intended to differentiate defining from contributing causalrelationships). The quality attribute reliability provides a good case in point. Abstract properties like fault-tolerance and recoverability are determinates of reliability. The issue is, are fault-tolerance and recoverability defining behaviours of reliability or software characteristics that contribute to reliability. What we are confronting here is the tension between top-down definition of quality attributes and bottom-up characterisation (that is, abstract description) or classification of software properties (both non-functional and functional properties) that contribute to high-level quality attributes. Whether we regard fault-tolerance as a behaviour or a software characteristic does not really matter. What is important to recognise is that we have two avenues for arriving at our goal. Some properties, like modularity or correctness, are clearly software characteristics rather than behaviours or uses. With others like fault-tolerance, it is not so easy to make the distinction. The underlying intuition we are using in making such distinctions is that behaviours tend to be system-wide qualities whereas it is meaningful to associate software characteristics with particular components as well as with an overall system. We can circumvent this issue using determinable-determinate decompositions. As an example, in ISO-9126 [7] the determinable, reliability can be decomposed into the determinates availability, fault-tolerance, maturity and recoverability (more will be said about this later). Schematically we have:

Reliability

| Fault-tolerence | Recoverability |

|---|

The following diagram illustrates this notion schematically. Subordinate uses may in turn be hierarchically defined, e.g.

Uses

|

22/09/09 | 17:10 |

|---|

Software Product Quality 9

The quality attributes of a quality model should be sufficient to meet the needs of all interest groups associated with the software

Each high-level quality attribute of software is characterised by a set of subordinate properties which are either behaviours, uses or software characteristics.Each software characteristic (determinable) is determined by a subordinate set of software characteristics (determinates) or is contributed to by a set of tangible properties that we will call quality-carrying properties.

| 22/09/09 | 17:10 |

|---|

Software Product Quality 10

QUALITY MODEL

| . . . |

|---|

|

c |

|

. . . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| . . | . . . |

|

|

. . . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Usability | . . |

17:10 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Software Quality Institute | 22/09/09 | ||

In order to arrange these properties into an appropriate hierarchy using the definition/characterisation strategy we have described we first classify the properties as either behaviours, uses, software characteristics or tangible properties according to our definitions of these terms (see below).

|

|---|

Consistency

Transparency

| Learnability |

|---|

| Operability | Responsiveness |

|---|

Hot-keyed

What we have provided here is a long way short of a comprehensive generic specification of usability. Hopefully however, enough detail has been given to illustrate what is entailed in carrying out such a process. Note that the property Foreign Language Provision that was in our original list would end up being a determinate of customisability. It is therefore not shown in the hierarchical specification above but would appear as a subordinate software characteristic in the complete model. Limiting behaviours, uses and software characteristics to either one or two levels of hierarchy would appear to be sufficient and practical. It conforms to the determinable-determinate model of definition/characterisation.

| 22/09/09 | 17:10 |

|---|

A defensible functional model for reliability in this context is to say that at the highest level there are four non-overlapping classes of functionality (tangible properties) that a system must implement to exhibit reliable behaviour: error-detection (caused by (a) and (b) type faults), error-reporting, fault-diagnosis and error-resolution. The previous functionality deals only with situations where the system is able to avoid failure (i.e, the system exhibits the subordinate behaviour of reliability – that is, fault-tolerance). There is also another kind of functionality needed to recover/restart after failure of the software system and/or failure of external sub-systems that the software system interfaces with. We refer to this behaviour as recoverability. Within this functionality there may be varying degrees of sophistication, completeness and alternative strategies for dealing with the situation. For example reconfigurability and survivability (the behaviour where a system needs to continue operating when one or more of its sub-systems have ceased to function) are subordinate behaviours of recoverability. In some applications a behaviour like survivability may be such a critical quality requirement that there is justification for raising it to the same level as reliability even though technically it is just a very specialised form of reliability.

Suitable metrics which characterise the reliability of a software system are the behaviours maturity and availability. Maturity may be characterised/measured as a running average of the elapsed-time between failures over the life-time of the system thus far while availability may be interpreted as a running average of the percentage derived from the system down-time relative to the total elapsed time. Below we show a first level characterisation for the quality attribute reliability based on our top-down functional model/metrics model characterisation of reliability

| 22/09/09 | 17:10 |

|---|

| Software Product Quality | 13 | |

|---|---|---|

4.1.2 A Possible Instantiation of a Generic Quality Model

Below we provide a possible (but not definitive) generic instantiation of the quality model. It bears many similarities with ISO-9126 apart from the inclusion of Reusability at the top-level and the inclusion of some additional subordinate properties. From Functionality down to Maintainability we are talking about a single software/hardware/system environment. Beyond that we have included quality attributes that reflect considerations for use in other environments. A generic proposal like this is intended as a possible high-level starting point for developing a tailored/adapted/augmented quality model for any specific project.

| 22/09/09 | 17:10 |

|---|

Software Product Quality 14

requirements. Settling the quality needs of the different interest groups is at best an informal process. One possible, although defensible high-level needs specification is: suitability (or fitness-for-purpose which is characterised by a set of behaviours of the software), usability, and adaptability (which is characterised by a set of uses of software by different interest groups). Below we show a mapping onto a modified/extended version of ISO-9126 [7]. The primary interests of clients/sponsors are in the suitability of a software system for its intended purposes. The behaviours, functionality, reliability and efficiency provide an accurate high-level characterisation of suitability. In contrast users and developers/maintainers are interested in the usability and adaptability of a software system which reflect the different uses of the system. The high-level uses, usability, portability, maintainability and reuse often represent priority quality needs of these interest groups. Of course, sponsors may also be interested in maintainability, etc. In some instances, at least, this will be a secondary quality need for this interest group, and so on

| Users |

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Usability | Adaptability | ||||||

| Reliability |

|

Efficiency | Operability | Portability | |||

|

|||||||

Instantiated generic quality models like this are never absolute or fixed, either in terms of the chosen primary interest groups or in terms of the set of high-level quality attributes that we settle upon. If we had chosen to include auditors as a primary interest group then we would have had to add the high-level quality attribute, verifiability which is a high-level use of software. The point we are trying to make here is that quality needs vary in different contexts and for different projects. However the framework that we are proposing is robust and flexible enough to accommodate variability, change and refinement. Tailoring is going to be necessary for any given project to accommodate and get the right emphasis and balance to meet specific project quality requirements.

| 22/09/09 | 17:10 |

|---|

4.2 Software Product Model

At the heart of constructing a software product model are two fundamental assumptions:

|

||

|---|---|---|

|

||

|

|---|

The following set of statements assist us in constructing a software product model:

Software exhibits behaviours and is open to uses – both these sets of properties are abstract

We choose to associate abstract properties with software, called software characteristics, in order to provide high-level descriptions of its nature, its behaviour, its uses, its support for change, its form and its structure. Examples are: machine-independence, modularity and correctness. Some software characteristics can be associated with particular types of software components.

|

22/09/09 | 17:10 |

|---|

|

22/09/09 | 17:10 |

|---|

| Correctness |

|

|

|---|---|---|

| System | ||

| Documentation |

|

|

| Architectural | ||

| Modularity | ||

| Structural | ||

| Data |

|

4.3 Linkage Model – Axioms of Software Product Quality

| 22/09/09 | 17:10 |

|---|

Software Product Quality 18

Our response to this question is embodied in the following set of axioms which form the building blocks for a linkage model and empirical theory of software product quality.

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|||

The second axiom stems from an observation linking behaviours, uses and quality attributes.

|

|---|

| 22/09/09 | 17:10 |

|---|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Software Product Quality 20

Our second choice is to have verifiable statements with premises that are capable of being checked by static analysis because such checking can be automated and it is repeatable, e.g.

Variables that are initialised prior to use in an expression contribute to

| Approximates |

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

The challenge in building a software product quality model is to align the properties associated with software’s nature (its software characteristics) with the properties that describe its desirable behaviours, ease-of-use and response to change (its quality attributes). In creating a linkage model we need to satisfy the following requirements:

| 22/09/09 | 17:10 |

|---|