Common worlds childhoods and pedago- gies website

4

ENGAGING WITH PLACE

| Copyright © 2017. Routledge. All rights reserved. |

|

|---|

Our Relationship

We meet on a winter’s day in the heart of Narrm (The Kulin [First People] word for Melbourne). Kelly, an arts-educator, and Catherine, an early childhood teacher educator and researcher, meet to discuss the possibility of Kelly under-taking some tutoring work at the university where Catherine co-ordinates a teacher education program. As we talk, we see the possibilities of embedding the arts into early childhood teacher education as a way to disrupt the traditional practices in early childhood education by moving beyond a technical, structured approach to meaning-making. Since that time, we have taught classes together that work to respectfully foreground Aboriginal worldviews. More recently, Kelly has become a mentor teacher in the Engaging with Place program. In the process

2012) draws on Latour’s notion of ‘common worlds’, the situated, everyday contexts in which we are all (human and non-human) entangled.

Found in Translation : Connecting Reconceptualist Thinking with Early Childhood Education Practices, edited by Nicola

Yelland, and Bentley, Dana Frantz, Routledge, 2017. ProQuest Ebook Central, http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/latrobe/detail.action?docID=516093 Created from latrobe on 2020-01-30 17:15:04.Traditional land owners : First People, who are the traditional custodians of the Land.

Reconciliation practices: Teaching and learning practices that intention- ally and respectfully foreground Aboriginal perspectives.

Learning circles: Tutorials are divided into small groups of student teachers to work collaboratively at university.

| Copyright © 2017. Routledge. All rights reserved. |

|

|---|

worldview of teaching and learning in early childhood is to engage with local places by foregrounding local expressions of Aboriginal culture as part of everyday moments of teaching and learning with young children. This work requires teachers to engage with complex ideas and concepts and to make visible a range of worldviews to inform teaching and learning. Fore-grounding local Aboriginal epistemologies attends to specifi c knowledges and practices and disrupts the idea of Aboriginal Australia as a homogenous, single culture group.

In Australia, the tensions of working to foreground Aboriginal perspectives in teaching and learning requires teachers to engage with all the histories, not just the sanitized colonial version. The histories relating to Aboriginal Australia are often silenced, rendered invisible and absent (Martin, 2007). In order to counter these absences, it is necessary to respectfully pay attention to Aboriginal perspectives of place, requiring us to “attend and attune to questions from the world” (Rautio, 2016). One of the ways we can attend respectfully to Aboriginal perspectives of place is to attune to the places around us in ways that do not always begin with a settler-colonial gaze. Disrupting the settler-colonial gaze requires us (settler colonials) to see places differently, in ways that attend to the ethics and politics of living on stolen land. It requires us (settler colonials) to engage with reconciliation discourses, discussions about treaty and the return of land to traditional Aboriginal own-ers. This action must include broad changes to structures and policies, not just token murmurings. This work is messy, fi lled with tension, and we must acknowledge that we are all ‘entangled and implicated in colonial histories’ (Duncan, Dawning & Taylor, 2015, p. 184). It is our ethical and political responsibility to not shy away from this messy work, even if it is unsettling and uncomfortable. To do this work with young children, we are required to rethink the perspectives that position them as being ‘innocent’, incapable of engaging with the uncomfortable realities of Australian history. We must learn

62 C. Hamm and K. Boucher

Worlds Research Collective, 2016). This conceptualisation of place requires us to acknowledge that we (humans) are always in relation to place. We are entangled in the histories, traumas, stories of places that are always already there. We present the everyday moments of practice in the university classroom and during the Engaging with Place placement as short narratives that work to make visible the ways in which we are respectfully foregrounding Aboriginal perspectives in teaching and learning. These narratives also show how we are enacting theory and concepts. Pedagogy and curriculum are situated as knowl-edge mobilization—ways to enact knowledge, rather than just storing content. Finally, we share professional conversations that mentor teacher Kelly has with student teachers during Engaging with Place as a way to bring together the concepts of place-thought and learning to be affected as methods of meaning-making and being present.

| Copyright © 2017. Routledge. All rights reserved. |

|

|---|

enact our conceptual thinking as pedagogy, working to make visible local Aboriginal epistemologies by shifting aside the layers of settler-colonial knowledges that dominate education frameworks.

Our work is also informed by the critical scholarship of Tuck and Wang (2012); Tuck and McKenzie (2015); Rose (2004); Martin (2007); Nakata (2002); and Pacini-Ketchabaw and Taylor (2015). These scholars work to raise critical questions that disrupt dominant settler-colonial perspectives. For example, attending to place in complex ways requires thinking beyond space or place as ‘culturally or politically neutral while perpetuating forms of European universalism’ (Mignolo, 2003, as cited in Tuck, McKenzie & McCoy, 2014, p. 1). Thinking with place from Aboriginal knowledge per-spective moves aside the layers of settler-colonial representations of place

64 C. Hamm and K. Boucher

interface’. Nakata (2002) describes this interface as colonial and Indigenous knowledges coming together. It is important that we do not back away from uncomfortable or unpleasant realities when these knowledges come together. For example, when engaging with Australian history, Aboriginal perspectives are intentionally foregrounded, rather than ‘defaulting’ to the dominant settler-colonial view. These practices generate possibilities for reimagining the way teachers engage respectfully with Aboriginal perspectives as part of their everyday work, creating opportunities for all children (Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal) to see, feel and hear Aboriginal culture in their classrooms every day, not just as a “grandslam approach” (Harrison & Greenfi eld, 2001). A grandslam approach refers to the way that Aboriginal perspectives can be taken up in education practices, often defaulting to homogenised stereotypes of Aboriginal culture. This approach limits the possibilities for teachers to engage in the practice of ‘being present’.

| Copyright © 2017. Routledge. All rights reserved. |

|---|

Found in Translation : Connecting Reconceptualist Thinking with Early Childhood Education Practices, edited by Nicola

Yelland, and Bentley, Dana Frantz, Routledge, 2017. ProQuest Ebook Central, http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/latrobe/detail.action?docID=516093 Created from latrobe on 2020-01-30 17:15:04.

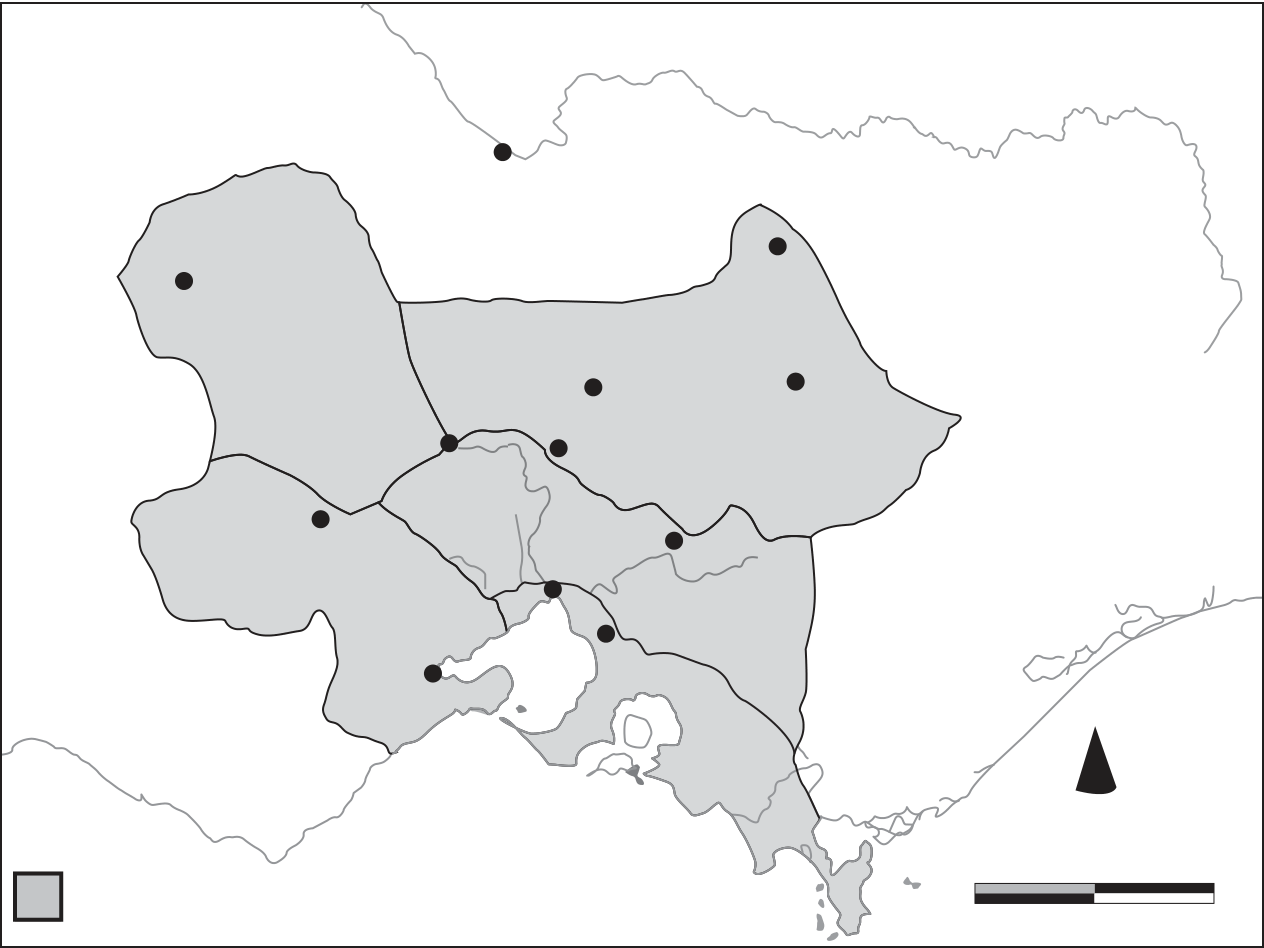

On the electronic whiteboard, I project a Kulin (Traditional Land Owners around Melbourne, Victoria) map and ask student teachers to identify whose country their home suburb is located on.

River

FIGURE 4.1 Kulin Map

Jacaranda. (2004, 14 September). The Kulin People. Retrieved from

In situating place as a pedagogical contact zone (Common Worlds Research Col-lective, 2016), we acknowledge that places are always in a state of entanglement of human and more-than-human others. The term contact zone (Haraway, 2008) gestures towards the ways in which entanglements occur. Haraway sees contact zones as entanglements of unknown, unpredictable, “diverse bodies and meanings [that] coshape one another . . . The partners do not precede the meeting; species of all kinds, living and not, are consequent on a subject and object-shaping dance of encounters” (p. 4). We fi nd the concepts, Place-Thought (Watts, 2013) and learning to be affected (Latour, 2004b), useful ways to make room for understand-ing place as a generative pedagogical contact zone . This framing attends to the ways in which places are entangled in all kinds of bodies and works to disrupt the settler-colonial imaginary of place. Thinking with place-thought and learning to be affected are concepts that underpin doing. New doings , or mobilizing knowledge, is required if we are to foreground Aboriginal perspectives and to shift away from the colonial gaze.

| Copyright © 2017. Routledge. All rights reserved. |

|

|---|

Student teachers think with Place-Thought as they complete their assessments, write weekly blogs, engage in class discussions and undertake their professional experience placement.

Learning to Be Affected

Each week, three student teachers and myself come together with a group of 4-year-olds to engage with this place by foregrounding local Aboriginal perspectives. I walk through the yard to a small pergola and put down the box I am carrying. The pergola is our gathering space. Out there beyond the fence is Cruickshank Park, a large parkland full of gumtrees and shrubs. I can also see Stony Creek, a small waterway connected to grasslands that make up the Victorian Volcanic Plain that stretches from the central north to the southwest of Victoria, Australia, covering an area of 2.3 million hectares (Friends of Iramoo , n.d. ). I begin to unpack the box I have brought with me. I pull out Bunjil the wedge tail eagle and Waa the crow hand puppets. Bunjil and Waa are creator spirits for Kulin people and hold great signifi cance in Kulin culture. I also pull out play materials that represent trees, fl owers and native animals. These materials refl ect Victorian Aboriginal culture and have been carefully selected to build curriculum for young children. This is an intentional practice as a way to highlight the diversities of Australian Aboriginal cultures.

|

|---|

Engaging With Place 69

Today we begin with a storybook set in the traditional lands of the Yorta Yorta people in Northern Victoria. Yurri’s Manung (Atkinson & Sax, 2013) is a story about a small nocturnal marsupial (a mammal, unique to Australia) who is looking for a warm place to sleep as the weather gets colder in her home, the Barmah forest. Yurri asks her animal friends if they have room for her in their homes—none of them do and she is left feeling cold. This story is about community, belonging and connection to place. With advice from their Aboriginal Elder, Yurri’s friends decide to work together to build her a Manung (a shelter) of her own.

|

|---|

Found in Translation : Connecting Reconceptualist Thinking with Early Childhood Education Practices, edited by Nicola

Yelland, and Bentley, Dana Frantz, Routledge, 2017. ProQuest Ebook Central, http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/latrobe/detail.action?docID=516093 Created from latrobe on 2020-01-30 17:15:04.

Engaging With Place 71

and investigation of ideas activates a pedagogy of place—a presencing of local stories, those present and not immediately accessible, rather than the importation of homogenised cultural cliches.

Found in Translation : Connecting Reconceptualist Thinking with Early Childhood Education Practices, edited by Nicola

Yelland, and Bentley, Dana Frantz, Routledge, 2017. ProQuest Ebook Central, http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/latrobe/detail.action?docID=516093 Created from latrobe on 2020-01-30 17:15:04.What we think clay is for shapes our experience with it, and the language we use to talk about the experience constructs particular meanings. If, on the other hand, we think about movement, place, impermanence, and relationality, then we may consider the possibility of moving toward and away from the clay, attending to the relationship of clay to its surround-ings, and inviting interaction with others.

(pp. 123–124)

| Copyright © 2017. Routledge. All rights reserved. |

|---|

Found in Translation : Connecting Reconceptualist Thinking with Early Childhood Education Practices, edited by Nicola

Yelland, and Bentley, Dana Frantz, Routledge, 2017. ProQuest Ebook Central, http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/latrobe/detail.action?docID=516093 Created from latrobe on 2020-01-30 17:15:04.

Engaging With Place 73

Found in Translation : Connecting Reconceptualist Thinking with Early Childhood Education Practices, edited by Nicola

Yelland, and Bentley, Dana Frantz, Routledge, 2017. ProQuest Ebook Central, http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/latrobe/detail.action?docID=516093 Created from latrobe on 2020-01-30 17:15:04.74 C. Hamm and K. Boucher

Friends of Iramoo. (n.d.). Western basalt plains grasslands @ Iramoo . Retrieved from

Friends of Stony Creek. (2015). Friends of Stony Creek website . Retrieved from

Jacaranda. (200 The kulin people . Retrieved from

Kind, S. (2010). Art encounters: Movements in the visual arts and early childhood educa- tion. In V. Pacini-Ketchabaw (Ed.). Flows, rhythms, and intensities of early childhood educa- tion curriculum (pp. 113–132). New York, NY: Peter Lang.

| Copyright © 2017. Routledge. All rights reserved. |

|

|---|

Library Associations Journal , 28 (5–6), 281–291.

Pacini-Ketchabaw, V., Nxumalo, F., & Rowan, M.C. (2014). Researching neoliberal and neocolonial assemblages in early childhood education. International Review of Qualitative Research , 7 (1), 39–57.

Pacini-Ketchabaw, V & Taylor, A. (2015). (Eds.) Unsettling the colonial places and spaces of early childhood education. NY & London: Routledge.

Taylor, A., & Giugni, M. (2012). Common worlds: Reconceptualising inclusion in early childhood communities. Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood , 13 (2), 108–119. Tuck, E., & Yang, K.W. (2012). Decolonization is not a metaphor. Decolonization: Indigene- ity, Education & Society , 1 (1), 1–40.

Watts, V. (2013). Indigenous place-thought and agency amongst humans and non humans (First Woman and Sky Woman go on a European world tour!). Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society , 2 (1), 20–34.