Berlin mouton gruyter the author language and linguistics compass

Language and Linguistics Compass 8/5 (2014): 171–187, 10.1111/lnc3.12075

Abstract

The distribution of reflexive anaphors has long been of central importance in the development of syntactic theory. In a parallel fashion, research on the comprehension of reflexive anaphors is increasingly influential for theories of syntactic comprehension. In this article, I present the problem of selecting a reflexive’s antecedent as a memory retrieval problem and illustrate why the comprehension of reflexives is of special interest for theories of the memory architecture of the sentence processor. I review a range of influential findings on reflexive comprehension, focusing on results that concern the speed and grammatical accuracy of antecedent retrieval. An emerging empirical generalization is that reflexives are relatively immune to retrieval interference, a property that sets them apart from superficially similar syntactic dependencies like subject–verb agreement. Existing data, across languages and across methodologies, suggest that comprehenders retrieve a reflexive’s antecedent primarily on the basis of its syntactic position.

Constraining Anaphoric Reference

Diverse theoretical accounts of the licensing constraints on reflexives seek to capture one core generalization: reflexive anaphors are licensed when their antecedent is in a structurally

The examples in (2) illustrate the role that locality and syntactic prominence play in licensing reflexives. An example like (2a) is ungrammatical because the antecedent John is too structurally distant from the reflexive, and in (2b), John is not structurally prominent enough to antecede the reflexive.

(2) a. *Johni thinks Mary disguised himselfi.

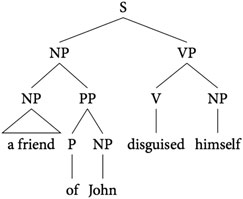

b. [A friend of [ Johni]]j disguised himself*i/j

| (3) |

|---|

Fig 1. A syntactic parse of the sentence A friend of John disguised himself.

Anaphoric Reference and Memory Search

Much research has been devoted to asking whether binding constraints like Principle A are implemented as early filters on the process of generating a set of candidate antecedents for an anaphoric expression (Badecker and Straub 2002; Nicol 1988; Nicol and Swinney 1989; Sturt 2003a,b). Here, I pose this question as a question of memory search: when searching for a reflexive’s antecedent, do comprehenders limit their search only to syntactically licensed antecedent positions? Put this way, reflexives are of significant interest for researchers interested in the memory architecture of the sentence processor. If antecedent selection involves memory access, then we must provide answers to at least the following two questions:

THE STATUS OF ANTECEDENTS: ACTIVE VERSUS PASSIVE MAINTENANCE

Theories of referential processing commonly distinguish between active and passive maintenance of antecedent representations. On active maintenance models, possible antecedents are maintained in an active state or buffer, and pronominal reference is achieved by linking pronouns to antecedents that are highly available or attended to in this way (Chafe 1974; Greene et al. 1992; Gundel 1999; Karmiloff-Smith 1980). Borrowing terminology from the working memory literature, we may say that such accounts maintain possible antecedents in focal attention (McElree 2001, 2006; McElree and Dosher 1989; McElree et al. 2003; Oberauer and Hein 2012).

Online eye-tracking measures provide a second measure of evidence in support of the claim that a reflexive must retrieve its antecedent. The visual world eye-tracking results of Runner and colleagues (2003, 2006) showed that comprehenders looked to the antecedent of a reflexive at the offset of the anaphor but not before (see also Clackson et al. 2011; Kaiser et al. 2009). Similar reactivation profiles have also been observed for long-distance reflexives in Korean (Han et al. 2010). However, the need to reactivate an antecedent may vary as a function of syntactic environment: in Kaiser et al. (2009)’s experiment 3, it appears that comprehenders may retain an active focus on a possessor argument (e.g. Bill in Bill’s picture of himself) throughout the comprehension of the picture NP.

© 2014 The Author Language and Linguistics Compass 8/5 (2014): 171–187, 10.1111/lnc3.12075 Language and Linguistics Compass © 2014 John Wiley & Sons Ltd

The second sub-question concerns the retrieval mechanism. There are at least two classes of candidate mechanism (McElree et al. 2003): cue-based direct-access retrieval or search mechanisms. Cue-based direct-access models access stored representations by matching a set of features (cues) against the contents of working memory. The representation that best matches those cues is then retrieved and restored to focal attention. Retrieval is content-addressable: representations are retrieved based on their content rather than their position in memory. Alternatively, stored representations may be retrieved with a search mechanism. Search mechanisms retrieve representations based on their location in memory and may be implemented using either serial or parallel comparison processes over some positionally defined search set (see Townsend and Ashby 1983).

Direct-access retrieval and search mechanisms make distinct predictions about the time course of memory access and what representations will cause interference. The signature prediction of direct-access retrieval models is that the time needed to retrieve a representation does not grow as the search space grows. Instead, representations that match the retrieval cues are always retrieved in constant time even if they differ in the strength or quality of encoding (McElree and Dosher 1989; McElree et al. 2003; McElree 2006). In contrast, search mechanisms generally predict that access times should grow with the search set. Retrieval mechanisms may also be distinguished with respect to the phenomenon of retrieval interference. In a content-addressable architecture, any representation that overlaps with the retrieval cues may contribute to retrieval interference. To the extent that search mechanisms predict such interference at all, it should arise only from representations in a positionally defined search set.

Time course data also implicate the use of a cue-based retrieval mechanism during sentence comprehension. Questions of time course have primarily been studied using the speed-accuracy trade-off (SAT) technique, which allows for direct modeling of the time course of retrieval (see McElree 2006). SAT data suggest that the size of the search set does not in general impact the speed with which comprehenders retrieve syntactic dependents for a number of linguistic dependencies: cross-sentential anaphora (Foraker and McElree 2007), VP ellipsis (Martin and McElree 2008), subject–verb integration (McElree 2000; McElree et al. 2003; Van Dyke and McElree 2011), filler-gap dependencies (McElree et al. 2003), and sluicing (Martin and McElree 2011). These results provide further support for the use of a direct-access, cue-based retrieval mechanism during sentence comprehension.

Against this background, the processing of antecedent-reflexive dependencies takes on particular interest. As I document below, current empirical evidence suggests that the construction of reflexive dependencies is relatively immune from retrieval interference, and what little time course data there is suggests that antecedent retrieval may not have the direct-access property observed for other dependencies. These data raise interesting questions of how and why memory access should vary across different linguistic dependencies and what conclusions this licenses about the memory architecture of the sentence processor.

Since Nicol’s original findings, a number of other studies have corroborated this conclusion. Important evidence in favor of this conclusion comes from experimental paradigms that explicitly manipulate the degree of interference from inaccessible antecedents. In a widely-cited paper, Sturt (2003a) used eye-tracking while reading to investigate short discourses as in (5) (Experiment 1) and (6) (Experiment 2):

(5) Jonathan was pretty worried at the City Hospital.

c. She remembered that the surgeon had pricked himself with a needle. d. #She remembered that the surgeon had pricked herself with a needle.

© 2014 The Author Language and Linguistics Compass 8/5 (2014): 171–187, 10.1111/lnc3.12075 Language and Linguistics Compass © 2014 John Wiley & Sons Ltd

| (6) | Syntactic Memory and Reflexives | 177 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| a. | ||||

Jennifer was pretty worried at the City Hospital

c. |

|---|

| (7) a. b. |

|

|---|

Both experiments showed that comprehenders read the reflexive region more slowly when the subject was complex, but this pattern was also seen in control conditions that had a lexical object in place of a reflexive. Because the presence of a reflexive did not interact with the presence of an inaccessible antecedent inside the subject NP, these data suggest that the search set for a reflexive effectively includes only the grammatically licit subject NP. In another paper that used self-paced reading, Badecker and Straub (2002) failed to find interference effects from genitive possessor NPs (Experiment 5) or experiencer arguments of raising predicates (Experiment 6).

© 2014 The Author Language and Linguistics Compass 8/5 (2014): 171–187, 10.1111/lnc3.12075 Language and Linguistics Compass © 2014 John Wiley & Sons Ltd

178 Brian Dillon

Using eye-tracking, Dillon and colleagues observed agreement attraction in structures like (9b): comprehenders showed eased processing of the ungrammatical verb form were when the structurally illicit NP middle manager(s) was plural compared to when it was singular. This pat-tern suggests that comprehenders failed to detect ungrammatical agreement dependencies (a so-called illusion of grammaticality) in the presence of a feature-matched distractor NP. Dillon and colleagues argued that this pattern provides critical evidence that comprehenders had misretrieved the inaccessible NP middle managers and used its feature values to license the agreement on the verb. In contrast, there was no interference from the inaccessible NP for minimally different reflexive dependencies, as in (9a). The contrast between agreement and reflexives is striking, as the retrieval necessary to license both agreement and reflexive dependencies must access the same subject position.

Given the central role that coargumenthood plays in some theoretical accounts of reflexives (Pollard and Sag 1992; Reinhart and Reuland 1993), one might wonder if the lack of retrieval interference observed in these studies reflects the fact that the reflexive and its antecedent were almost always coarguments of the same predicate. To test this possibility, Cunnings and Sturt (2012) used examples like (5) with picture noun phrase (PNP) reflexives both with and without a possessor (e.g. a/Bill’s picture of himself). In possessorless PNP constructions, the reflexive and its antecedent are not coarguments of the same predicate. Using eye-tracking while reading, they replicated Sturt’s (2003a) findings: there was no effect of interference on these reflexives from grammatically inaccessible antecedents. Thus, it appears that coargumenthood is not a precondition for grammatically accurate retrieval.

| Syntactic Memory and Reflexives | 179 | |

|---|---|---|

|

||

In an offline picture interpretation experiment, Clackson and colleagues found that adult participants uniformly chose the local subject Mr. Jones as the antecedent for the reflexive. In a visual world experiment, adults showed no significant increase in looks to the inaccessible antecedent in the double match condition relative to the single match condition. Thus, even when the reflexive was not an obligatory coargument of its antecedent, Clackson and colleagues still failed to observe interference from inaccessible antecedents.

b. |

|

|---|

© 2014 The Author Language and Linguistics Compass 8/5 (2014): 171–187, 10.1111/lnc3.12075 Language and Linguistics Compass © 2014 John Wiley & Sons Ltd

180 Brian Dillon

| (13) a. b. |

|---|

Interference from inaccessible antecedents also arises under conditions where one might expect comprehenders to have difficulty in recovering a reliable parse of the input. Nicol (1993; reported in Nicol and Swinney 2003) reports a replication of her original studies using RSVP rather than auditory presentation. In contrast to the CMLP studies, she found that in the visual modality, comprehenders reactivated the linearly closest antecedent at the reflexive, even if it was not grammatically licit. She suggested that the demanding RSVP presentation made it difficult for readers to develop fully articulated syntactic representations, and so they could not use a syntactic parse to support accurate retrieval of an antecedent.

Similarly, for populations who may have difficulty constructing syntactic parses online, there is evidence for interference from inaccessible antecedents in comprehension. Clackson et al. (2011) compared the performance of children, aged 6 to 9, to adults. Although the children mastered the binding principles in offline tests, in Clackson et al’s visual world task, children showed a significant increase in looks to the inaccessible antecedent in double match conditions (Peter in (10a)). Felser et al. (2009) and Felser and Cunnings (2012) found that Japanese and German learners of English were more susceptible to interference from

Lastly, in cases where the grammatical constraints on reflexives are subject to debate, it can be difficult to tease apart the effects of retrieval interference from inappropriately characterized grammatical constraints. For instance, Runner et al. (2003, 2006) report visual world data on the processing of possessed picture noun phrase (PPNP) reflexives. They monitored the eye movements of participants across a visual display when given instructions such as the following:

(14) Pick up Joe. Look at Ken. Have Joe touch Harry’s picture of himself.

182 Brian Dillon

Dillon and colleagues used the speed-accuracy trade-off technique and found that local construals of the Mandarin long-distance reflexive ziji were processed more quickly when the antecedent was in the local clause compared to when the antecedent was in a more distant clause. Similar results have been observed for probe recognition studies. Gao and colleagues (2005) and Liu (2009) observed activation of local antecedents at short SOAs following the presentation of ziji and activation of more distant antecedents only at longer SOAs. Li and Zhou (2010) present ERP evidence that comprehenders retrieve an antecedent in the local clause more easily than an antecedent in a non-local clause.

© 2014 The Author Language and Linguistics Compass 8/5 (2014): 171–187, 10.1111/lnc3.12075 Language and Linguistics Compass © 2014 John Wiley & Sons Ltd

Syntactic Memory and Reflexives 183

antecedent (Kreiner et al. 2012). Likewise, Kaiser et al. (2013) report visual world data that show a very early influence of discourse constraints on logophoric reflexives.

Another critical difference between reflexives and other interference-prone dependencies

Conclusion

Overall, the current data suggest that comprehenders use a sophisticated memory access mechanism that displays a relatively interference-free retrieval profile. This relative immunity to interference sets reflexives apart from other well-studied cases of retrieval interference in syntactic comprehension. One important conclusion these data license about the memory architecture of the sentence processor is that retrieval interference is not a hard, unavoidable

syntactically licensed positions. However, many important theoretical questions remain unresolved. Before firm conclusions about the specific retrieval mechanism can be drawn, further research on the time course of antecedent retrieval is required. It also remains unclear why reflexives should show the distinct retrieval profile that they do, and so, much further research is necessary to tease apart the representational and processing factors that may underlie this difference.

Acknowledgement

* Correspondence address: Brian Dillon, Department of Linguistics, 226 South College, University of Massachusetts, 150 Hicks Way, Amherst, MA 01003, USA. E-mail: brian@linguist.umass.edu

Works Cited

Broadbent, D. E. 1958. Perception and communication. New York: Oxford University Press.

Büring, D. 2005. Binding theory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Syntactic Memory and Reflexives 185

——. 1986. Knowledge of language. New York: Praeger.

Corbett, A. T., and F. R. Chang. 1983. Pronoun disambiguation: accessing potential antecedents. Memory & Cognition 11(3). 283–94.

Cowan, N. 1995. Attention and memory. New York: Oxford University Press.

Dillon, B., W.-Y. Chow, M. Wagers, T.-M. Guo, F. Liu, and C. Phillips. 2010. The structure sensitivity of memory access: evidence from Mandarin Chinese. Talk presented at the 23rd annual CUNY Human Sentence Processing Conference. New York: New York University.

Dillon, B. 2011. Structured access in sentence comprehension. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Maryland. Dillon, B., A. Mishler, S. Sloggett, and C. Phillips. 2013. Contrasting intrusion profiles for agreement and anaphora: experimental and modeling evidence. Journal of Memory and Language 69. 85–103.

Gao, L., Z. Liu, and Y. Huang. 2005. Who is ziji? An experimental research on binding principle. Linguistic Science 2. 39–50. Gernsbacher, M. A. 1989. Mechanisms that improve referential access. Cognition 32(2). 99–156.

Gordon, P. C., R. Hendrick, and M. Johnson. 2001. Memory interference during language processing. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition 27(6). 1411.

Harris, T., K. Wexler, and P. Holcomb. 2000. An ERP investigation of binding and coreference. Brain and Language 75(3). 313–46.

Jackendoff, R. 1972. Semantic interpretation in generative grammar. MIT Press: Cambridge MA.

186 Brian Dillon

Karmiloff-Smith, A. 1980. Psychological processes underlying pronominalization and non-pronominalization in children’s connected discourse. Papers from the parasession on pronouns and anaphora, ed. by J. Kreiman and E. Ojedo, 231–50. Chicago: Chicago Linguistics Society.

Kreiner, H., S. Garrod, and P. Sturt. 2013. Number agreement in sentence comprehension: The relationship between grammatical and conceptual factors. Language and Cognitive Processes 28(6). 829–874.

Kuno, S. 1972. Pronominalization, reflexivization, and direct discourse. Linguistic Inquiry 3(2). 161–95.

Li, X., and X. Zhou. 2010. Who is ziji? ERP responses to the Chinese reflexive pronoun during sentence comprehension. Brain Research 1331. 96–104.

Liu, Z. 2009. The cognitive process of Chinese reflexive processing. Journal of Chinese Linguistics 37(1). 1–27. Martin, A., and B. McElree. 2008. A content-addressable pointer mechanism underlies comprehension of verb-phrase ellipsis. Journal of Memory and Language 58. 879–906.

McElree, B., and B. Dosher. 1989. Serial position and set size in short-term memory: time course of recognition. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General 18. 346–73.

——. 1993. Serial retrieval processes in the recovery of order information. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General 122. 291–315.

Nicol, J. L., and D. Swinney. 1989. The role of structure in coreference assignment during sentence comprehension. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research 18. 5–19.

——. 2003. The psycholinguistics of anaphora. Anaphora: a reference guide, ed. by W. Barss, 72–104. Oxford: Blackwell.

Patil, U., S. Vasishth, and R. Lewis. 2011. Early retrieval interference in syntax-guided antecedent search. Oral presentation at the Annual Meeting of the CUNY Conference on Human Sentence Processing. Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University.

© 2014 The Author Language and Linguistics Compass 8/5 (2014): 171–187, 10.1111/lnc3.12075 Language and Linguistics Compass © 2014 John Wiley & Sons Ltd

Reinhart, T. 1976. The syntactic domain of anaphora. Ph.D. dissertation, Massachusetts Institute of Technology.——. 1983. Anaphora and semantic interpretation. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Reinhart, T., and E. Reuland. 1993. Reflexivity. Linguistic Inquiry 24(4). 657–720.

——. 2003b. A new look at the syntax-discourse interface: the use of binding principles in sentence processing. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research 32(2). 125–39.

——. 2013. Constraints on referential processing. Sentence processing, ed. by R. van Gompel, 136–59. Routledge, London: Psychology Press.

Van Dyke, J. A., and C. L. Johns. 2012. Memory interference as a determinant of language comprehension. Language and Linguistics Compass 6(4). 193–211.

Van Valin, R. D., and R. J. LaPolla. 1997. Syntax: structure, meaning, and function. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.