And ultimately the reactor containment building

Last Update: August 16, 2021

(Lecture 1.1) Risk and Safety of Engineered Systems (RSANS: pp. 1-13)

E. Reliability, Availability, Maintainability, and Safety

A. Risk and Its Perception and Acceptance

1. voluntary vs involuntary risks,

2. distributed vs acute or catastrophic risksAcceptability of risk is often inversely proportional to the consequences as illustrated using the risk space shown in Figure 1. Events in the upper right quadrant, entailing significant consequences and significant unfamiliarity or limited observability, generally require strict regulations and analyses that are often subject to public skepticism.

What distinguishes everyday life risks from those from the operation of a nuclear power plant? An important distinction in whether an individual accepts a risk is whether he or she has control over the risk to be incurred. Other factors are:

1. voluntary vs involuntary,

2. distributed vs acute or catastrophic consequences 3. immediate vs latent consequences

4. short term vs long term consequences

5. reversible vs irreversible consequences

6. no alternatives vs many alternatives available 7. small vs large uncertainty

8. common vs unknown hazard

9. exposure is necessary vs exposure is optional 10. incurred occupationally vs nonoccupationally 11. incurred vs not incurred by other people

| 10-1 | 95thPercentile | |

|---|---|---|

| 10-2 | Mean |

| 10-9 |

|

|---|

1 10 100 1,000 10,000 100,000

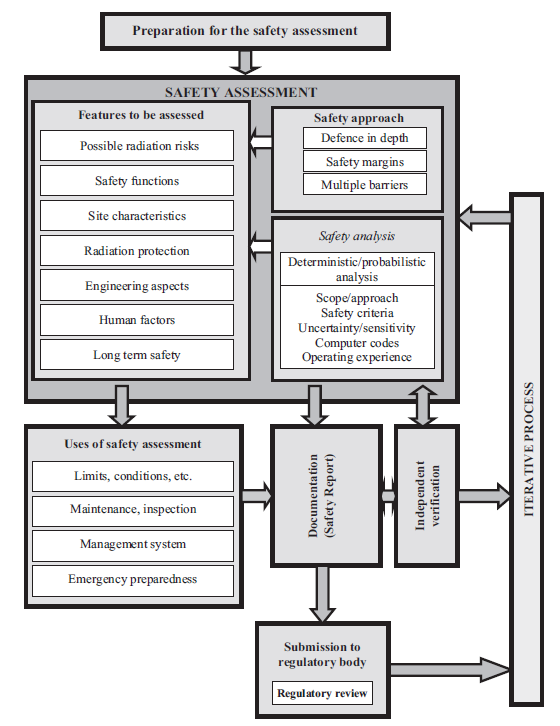

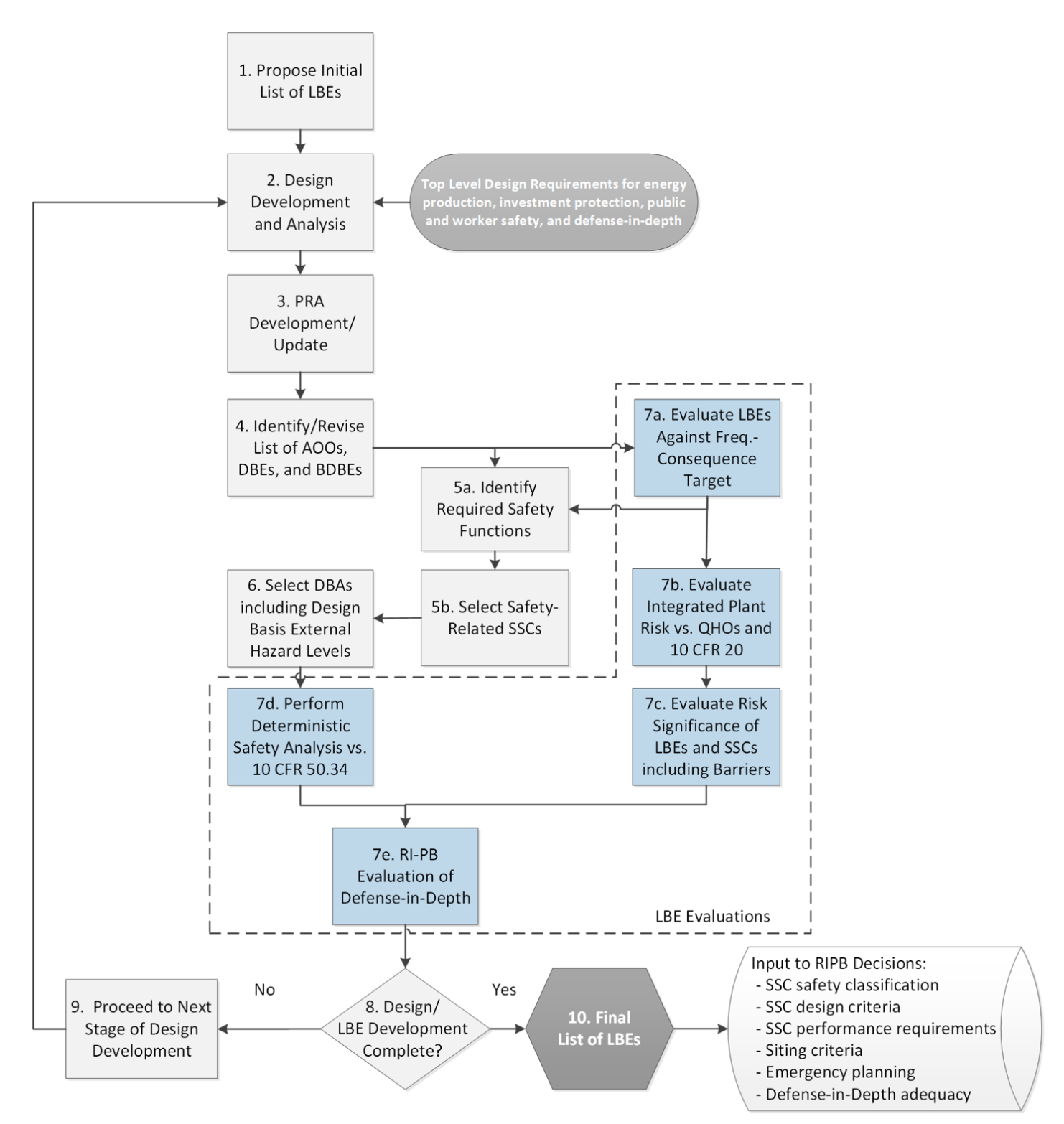

The objective of a risk analysis is to predict what might happen, beginning with an undesired initiating event and following that event in time to predict an undesired consequence if the active and passive safety systems fail to perform their intended function. On the other hand, the objective of a safety analysis is to design the components of a system so that undesired initiating events do not occur or, if they do, that backup systems intervene in the progression of following events to prevent or mitigate any undesired consequences.

A cornerstone of the risk and safety assessments for nuclear systems is the principle of defense in depth (DID), originating from the various safety measures that Enrico Fermi and his colleagues incorporated in the planning and execution of the first self-sustaining chain reaction at the University of Chicago in 1942. Thus, the DID principle has been implemented at every stage of design, construction, and operation of nearly every nuclear reactor around the world, with an ultimate objective of protecting the health and life of the population at large, although some people would argue that this was not done with the Russian RBMK reactors. The principle may be accomplished through the diversity and redundancy of various equipment and safety functions. The safety principle may also be represented in terms of multiple layers of radiation barriers, including the fuel matrix, fuel cladding, reactor pressure vessel, and ultimately the reactor containment building. In terms of safety functions, three basic levels may be illustrated:

i. prevention of accidents via reactor shutdown,

ii. mitigation of accidents through the actuation of an auxiliary coolant system, and iii. protection of the public via containment sprays minimizing the release of radionuclides to the environment.the public. The General Design Criteria (GDC), promulgated as Appendix A to Title 10, Code of Federal Regulations, Part 50, establish minimum requirements for the principal design criteria for water-cooled nuclear power plants similar in design and location to plants for which construction permits have been issued by the Nuclear Regulatory Commission. The DID principles are fully reflected in the General Design Criteria. Example: “Criterion 62—Prevention of criticality in fuel storage and handling. Criticality in the fuel storage and handling system shall be prevented by physical systems or processes, preferably by use of geometrically safe configurations.”

Figure 5. Frequency-Consequence Target (NEI 18-04)

C. Three Historical Reactor Accidents

complex operated by Tokyo Electric Power Company (TEPCO). Despite the valiant effort made by TEPCO to keep the reactor cores and used fuel pools replenished with water, the reactor cores were severely damaged with a significant meltdown of the fuel rods and contamination of the entire FD site, which will require decommissioning all six units. No acute health effects due to the radiation exposure from the FD accident have been reported and indeed the long-term health effects of radiation exposure due to the FD accident may be almost negligible. Thus, the FD accident could perhaps be evaluated in the bigger context of the natural disaster that caused possibly as many as 17,500 deaths and countless residents to become homeless.

D. Definition of Risk

i. What can go wrong?

ii. What is the likelihood if it does go wrong? iii. What are the consequences?

To express the concept of risk in more mathematical terms, risk ℛ! combines the frequency ℱ! of an event sequence 𝑖, in events per unit time, with the corresponding damage 𝐷!, which is the magnitude of the expected consequence. A traditional definition of risk is:

1 Kaplan, S., and B. John Garrick. 1981. “On The Quantitative Definition of Risk.” Risk Analysis 1 (1): 11–27. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1539-6924.1981.tb01350.x.

Usually, however, of more interest is the risk of damages 𝐷!(𝑥) exceeding the magnitude 𝑋, in which case the risk in Eq. (5) is replaced by:

(6)

(8)

E. Reliability, Availability, Maintainability, and Safety

Page 9

•Availability𝐴(𝑡) is the probability that a system can perform a specified function or mission under given conditions at time 𝑡.

The assumptions about the way a system degrades with age and how it responds to a failure affect the type of model that can be assumed for repair of a system. A minimal repair returns the system to the state the system was in immediately preceding failure, while a perfect repair or renewal repair returns it to the state it was in when new. However, when should the components be repaired? Maintainability is the ability of a system component, during its prescribed use, to be restored to a state in which it can perform its intended function when the maintenance is performed under prescribed procedures. In general, the frequency of maintenance actions is guided by experience and depends not only on the quality of a system’s components but also on the operating environment of the equipment.

Maintenance activities are usually classified as either preventive or corrective activities. Preventive maintenance (PM) is of the following types: clock-based (i.e., fixed schedule), age-based (i.e., age metric such as number of demands), and condition-based (i.e., variable threshold such as vibration). Corrective maintenance (CM), or in a simpler word repair, is carried out when an item has failed. Reliability-centered maintenance (RCM) provides a framework for developing optimally scheduled maintenance programs that are cost effective.