And party and party each get three party list seats

Democratic Electoral Systems Around the World, 1946-2011

Nils-Christian Bormann

ETH Zurich

| 1 | 1 |

|---|

1.2 Case Selection . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2

1.3 Missing Data . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2

1.5 Glossary . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10

References 34

• Bormann, Nils-Christian & Matt Golder. 2013. Electoral Studies.

To obtain the data, please click . In total, the data contain information on 1,197 legislative and 433 presidential elections that occurred in democracies from 1946 (or independence) through 2011.

3. es_data-v2_0_comments.xls

The first two data sets differ only in terms of their format: Stata or comma separated. The third data set, es_data-v2_0_comments.xls, adds (very brief) comments about specific variables for particular cases and indicates the sources that were consulted. The comments in this third data set will be expanded and incorporated into a much more detailed codebook as time permits.

There are three different types of missing data.

1. NA in the .csv file or . in the Stata file indicate that the variable cannot take on a meaningful value. For example, presidential elections do not have a meaningful value for those variables that relate to the electoral rules used in legislative elections.

The following variables provide identifying information about the election and country.

elec_id: This variable uniquely identifies each election. The variable begins with either an L or a P to indicate whether the election is legislative or presidential. The variable then includes a three letter abbrevia-tion of the country’s name, followed by the (first round) date (yyyy-mm-dd) of the election. For example, L-ARG-2001-10-14 uniquely identifies the legislative elections that took place in Argentina on Octo-ber 14, 2001, and P-USA-2008-11-4 uniquely identifies the presidential elections that took place in the United States on November 4, 2008.

region1: This is a categorical variable indicating the country’s region of the world (Przeworski et al., 2000).

1. Sub-Saharan Africa

2. South Asia

3. East Asia

4. South East Asia

5. Pacific Islands/Oceania

6. Middle East/North Africa

7. Latin America

8. Caribbean and non-Iberic America

9. Eastern Europe/post-Soviet states

10. Industrialized Countries (OECD)

11. Oil Countries

region3: This is a categorical variable indicating the country’s region of the world.

1. Sub-Saharan Africa

2. Asia

3. West (incl. US, Canada, Australia, New Zealand)

4. Eastern Europe/post-Soviet states

5. Pacific Islands/Oceania

6. Middle East/North Africa

7. Latin America/Caribbean

Gandhi and Vreeland (2010) for their eventual recoding of these countries as democratic. As an example, Cheibub, Gandhi and Vreeland (2010) do not code Liberia as democratic until 2006 despite the fact that presidential elections took place in October 2005, because the winner of these elections, Ellen Johnson-Sirleaf, did not officially take office until January 2006. The bottom line is that there are a few observations in our data set of democratic elections where regime indicates that the country was a dictatorship by the end of the year.

presidential: This is a dichotomous variable that takes on the value 1 if the election is presidential and 0 if the election is legislative.

1.4.2 Legislative Elections

The following variables provide information about (lower house) legislative elections only. They take on the value NA in the .csv file or . in the Stata file for presidential elections. Some variables relating to things such as the electoral formula or the number of electoral districts are specific to an electoral tier. Each of the variables that relate to a specific electoral tier is entered as tierx_varname, where x indicates the tier (1-4) and varname is the variable name. For example, tier3_formula indicates the electoral formula used in the third electoral tier. In what follows, we describe the variables but do not distinguish by electoral tier.

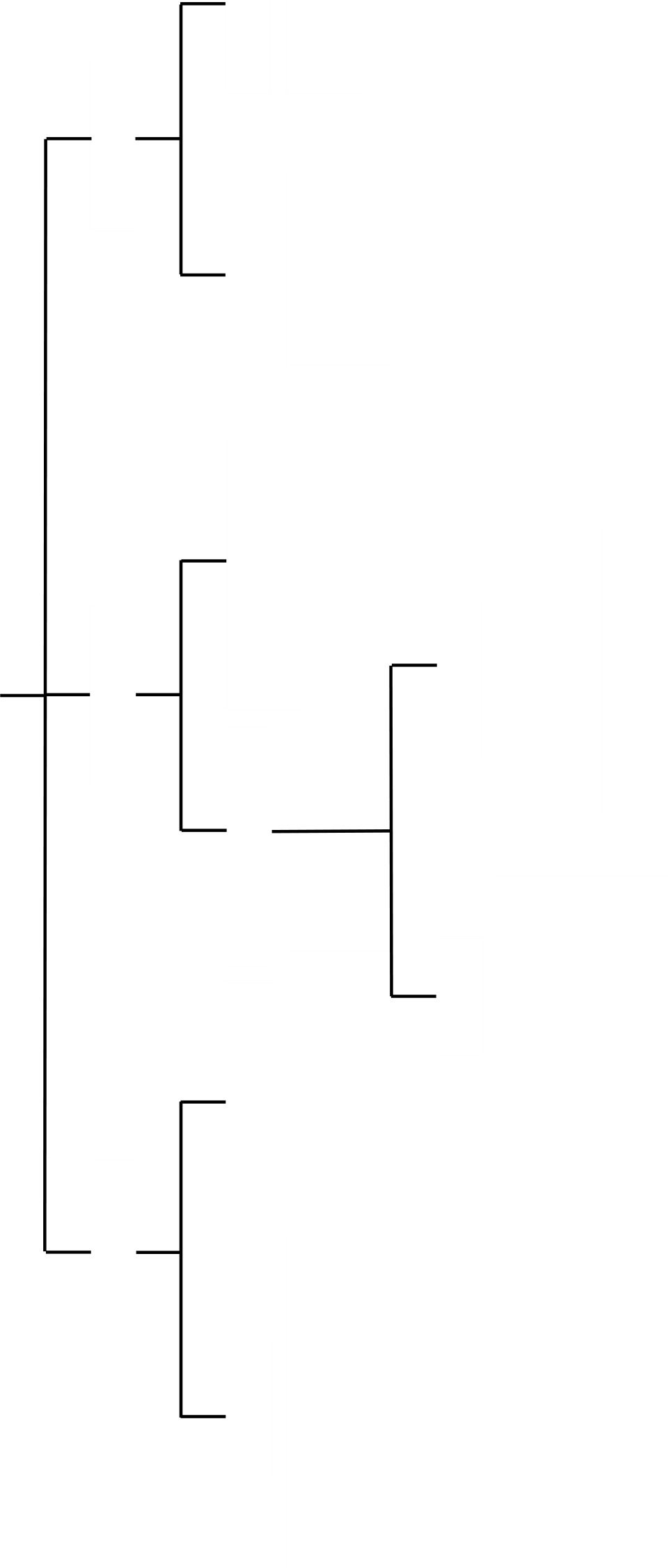

In Figure 1.1, we show the basic classification of electoral systems used in democratic national-level lower house legislative elections.

elecrule: This is a categorical variable that provides a more detailed indication of the type of electoral system used in the election.

6

7

7. Modified Borda Count (mBC)

8. Block Vote (BV)

9. Party Block Vote (PBV)

10. Limited Vote (LV)

11. Single Nontransferable Vote (SNTV)

12. Hare quota

13. Hare quota with largest remainders

14. Hare quota with highest average remainders

15. Hagenbach-Bischoff quota

16. Hagenbach-Bischoff quota with largest remainders

17. Hagenbach-Bischoff quota with highest average remainders 18. Droop quota

19. Droop quota with largest remainders

20. Droop quota with highest average remainders

21. Imperiali quota

22. Imperiali quota with largest remainders

23. Imperiali quota with highest average remainders

24. Reinforced Imperiali quota

25. D’Hondt

26. Sainte-Laguë

27. Modified Sainte-Laguë

28. Single Transferable Vote

5. Conditional

multi: This is a dichotomous variable that indicates whether there is more than one electoral tier (1) or not (0).

districts: This is the number of electoral districts or constituencies in an electoral tier. For exam-ple, tier1_districts is 17 and tier2_districts is 1 in the 2005 legislative elections in Den-mark, because there were 17 districts in the lowest electoral tier and 1 district in the next (national) tier; tier3_districts and tier4_districts are both 0 for this election because there were no higher electoral tiers.

avemag: This is the average district magnitude in an electoral tier. This is calculated as the total number of seats allocated in an electoral tier divided by the total number of districts in that tier. For example, tier1_avemag is135 17 = 7.94 in the 2005 legislative elections in Denmark, because 135 seats were allocated across 17 districts in the lowest electoral tier.

enpp_others: This is the percentage of seats won by parties that are collectively known as ‘others’ in official election results.

9

1. Plurality

2. Absolute Majority

1.5 Glossary

Much of the information in the glossary comes directly from Clark, Golder and Golder (2012, 535-602).

Table 1.1 provides an example of how the AV system works using the results from the Richmond con-stituency of New South Wales in the 1990 Australian legislative elections. When the first-preference votes from all of the voters were initially tallied up, Charles Blunt came first with 40.9 percent of the vote. Be-cause no candidate won an absolute majority, the candidate with the lowest number of votes (Gavin Baillie) was eliminated. As Table 1.1 illustrates, Baillie was ranked first on 187 ballots. These 187 ballots were then reallocated to whichever of the remaining candidates the voters ranked second after Gavin Baillie. For example, the fact that Ian Paterson received 445 votes in the first count but 480 votes in the second count indicates that 35 of the people who had listed Gavin Baillie as their most preferred candidate listed Ian Pa-terson as their second-choice candidate. Because there was still no candidate with an absolute majority after this second count, the new candidate with the lowest number of votes (Dudley Leggett) was eliminated and his ballots were reallocated among the remaining candidates in the same manner as before. This process continued until the seventh round of counting, when Neville Newell became the first candidate to finally obtain an absolute majority of the votes. The overall result, then, was that Neville Newell became the repre-sentative elected from the Richmond constituency of New South Wales.

Block Vote (BV): Majoritarian electoral systems include single-member district plurality, alternative vote, single nontransferable vote, block vote, party block vote, borda count, modified borda count, limited vote, and two-round systems. The block vote is essentially the same as the single nontransferable vote system except that individuals now have as many votes as there are seats in a district to be filled. When presented with a list of candidates from various parties, voters can use as many or as few of their votes as they wish; however, they can give only one vote to any one candidate. The candidates with the most votes are elected. This helps to explain why the block vote is sometimes referred to as plurality-at-large voting. See also Party Block Vote.

| (%) |

|

50.5 |

|

49.5 | 27.4 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (#) | |||||||||||

| 34,664 | 33,980 | ||||||||||

| Sixth Count |

|

29.4 | 43.2 | ||||||||

| (#) |

|

||||||||||

| Fifth Count | (%) | 27.1 | 24.1 | ||||||||

| (#) |

|

||||||||||

| 18,683 | 16,658 | ||||||||||

| Fourth Count | (%) |

|

26.9 | 41.2 | 23.8 | ||||||

| (#) | |||||||||||

| 18,544 | 28,416 | 16,438 | |||||||||

| Third Count | 26.8 |

|

41.0 | 23.5 | |||||||

| (#) |

|

530 | |||||||||

|

|

26.7 | 41.0 | 23.3 | |||||||

|

18,467 |

|

28,274 | 16,091 | |||||||

| First Count | (%) |

|

|

||||||||

| (#) |

|

|

|||||||||

| 18,423 | 28,257 | 16,072 | |||||||||

| Neville Newell |

|

|

Dudley Leggett | Helen Caldicott |

Civilian Dictatorship: There are three types of dictatorship: civilian, military, and royal. A civilian dic-tatorship is a residual category in that dictatorships that are not royal or military are considered civilian (Cheibub, Gandhi and Vreeland, 2010).

Coexistence Mixed Electoral System: There are five subcategories of mixed electoral systems. Coexis-tence, superposition, and fusion systems are independent mixed systems, while correction and conditional systems are dependent mixed systems. A coexistence system is one in which some districts in an electoral tier employ a majoritarian formula, while others employ a proportional formula. As an example, 82 seats in the 1998 legislative elections in Madagascar were allocated by majoritarian electoral rules (single-member district plurality) and 78 seats were allocated in 39 2-member districts using proportional representation (Hare quota with highest average remainders) (Nohlen, Krennerich and Thibaut, 1999, 536).

13

proportional component of the electoral system is used to compensate for any disproportionality produced by the majoritarian formula at the constituency level. This type of mixed system is sometimes referred to as a mixed member proportional (MMP) system. There are two subtypes of dependent mixed electoral systems: correction and conditional. The most common form of dependent mixed electoral system involves the use of majoritarian and proportional formulas in two separate electoral tiers (correction systems). For example, Germany elected half its legislators in the 2009 elections using a single-member district plurality system at the constituency level and the other half using proportional representation (Sainte-Laguë) at the state level in 16 regions. In most dependent mixed electoral systems, such as those used in Germany and New Zealand, individuals have two votes. They cast their first vote for a representative at the constituency level (candidate vote) and their second vote for a party list in a higher electoral tier (party vote). These types of mixed dependent systems allow individuals to give their first vote to a constituency candidate from one party and to give their second vote to a different party if they wish. This is called split-ticket voting. In systems in which voters have only one vote, the vote for the constituency candidate also counts as a vote for that candidate’s party.

Two issues crop up in dependent mixed systems. First, some candidates compete for a constituency seat but are also placed on the party list. You may wonder what happens if a candidate wins a constituency seat but is also placed high enough on a party list that she could win a party list seat as well. In this cir-cumstance, the candidate would typically keep the constituency seat, and her name would be crossed off

| Votes in Each Electoral district | National District | % of Votes | Seats Won | Total | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | Votes | Won | ||||

| Party A | 3,000 | 3,000 | 3,000 | 3,000 | 3,000 | 15,000 | 40 | 5 | 0 | 5 |

| Party B | 2,250 | 2,250 | 2,250 | 2,250 | 2,250 | 11,250 | 30 | 0 | 3 | 3 |

| Party C | 2,250 | 2,250 | 2,250 | 2,250 | 2,250 | 11,250 | 30 | 0 | 3 | 3 |

|

7,500 | 7,500 | 7,500 | 7,500 | 7,500 | 37,500 | 100 | 5 | 6 | 11 |

the party list. Second, some parties win more constituency seats than is justified by their party list vote. An example is shown in Table 1.3. Three parties competed for ten legislative seats. Party B and Party C each won 30 percent of the vote and so get three party list seats. They did not win any constituency seats, so they get to keep all three of their party list seats. Party A won 40 percent of the vote and so gets four party list seats. Party A, however, won all five of the constituency seats. What happens now? Well, Party A loses all of its party lists seats but gets to keep all five of its constituency seats. Overall, then, Party A gets five constituency seats, and Party B and Party C each get three party list seats. You’ll notice that the total number of allocated seats is eleven even though the original district magnitude was just ten. Because Party A won more constituency seats than its party list vote justified, the legislature in this example ends up being one seat larger than expected. This extra seat is known as an “overhang seat.” This means that the size of a legislature in a dependent mixed electoral system is not fixed and ultimately depends on the outcome of the election. In New Zealand’s 2005 legislative elections, the fact that the Maori Party won 2.1 percent of the party vote entitled it to three legislative seats. Because it won four constituencies, however, it ended up with four seats. As a result, the New Zealand legislature had 121 seats instead of the normal 120.

or highest average, systems. There are three common divisor systems in use around the world: D’Hondt, Sainte-Laguë, and Modified Sainte-Laguë. D’Hondt distributes seats among parties by first dividing the to-tal number of votes won by each party in a district by a series of numbers (divisors) to obtain quotients, and then allocating seats according to those parties with the highest quotients. D’Hondt uses the divisors 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, etc. In Table 1.16, we show how D’Hondt works in a ten-seat district in which 100,000 valid votes are split among parties A through F. The ten largest quotients are shown in boldface type. The exact order in which the ten district seats are allocated among these ten quotients is shown by the numbers in parentheses next to them. For example, Party A receives the first and second seat, Party B wins the third seat, Party C wins the fourth seat, Party A the fifth seat, and so on. Unlike quota systems, it is easy to see that divisor systems do not leave any remainder seats. The final allocation of the ten district seats is five to Party A, two each to Party B and Party C, and one to Party D.

Dictatorship: A dictatorship is a regime in which one or more the following conditions do not hold: (i) the chief executive is elected, (ii) the legislature is elected, (iii) there is more than one party competing in elections, and (iv) an alternation under identical electoral rules has taken place (Przeworski et al., 2000; Cheibub, Gandhi and Vreeland, 2010). There are three subtypes of dictatorships: civilian, military, and royal.

| Q = |

|---|

with the “decimal part” removed, where Vd is the total number of valid votes in district d and Md is the number of seats available in district d. In Table 1.5, we provide an example of how votes are translated into seats in a list PR system that employs the Droop quota. The results relate to a ten-seat district in which 100,000 valid votes are split among parties A through F. How many seats does each party win? The Droop quota in this case is100,000 10+1+ 1 minus the decimal part = 9, 091. Because Party A has 47,000 votes, it has 5.17 full quotas. This means that it automatically receives five seats. Following the same logic, Parties B, C, and D all automatically win one seat. You’ll have noticed that we have allocated only eight of the ten seats available in this district so far. There are two remainder seats that must still be distributed among

16

the parties. There are three common methods for distributing remainder seats: largest remainders, highest average, and modified highest average.

Treating independents and ‘others’ as a single party can be misleading, though, especially when these cate-gories are large. As a result, it may be preferable to use a “corrected” effective number of electoral parties based on the methods of bounds suggested by Taagepera (1997). This is enep1 in our data set. The method of bounds essentially requires calculating the effective number of parties treating the ‘other’ category as a single party (smallest effective number of parties), then recalculating the effective number of parties as if every vote in the ‘other’ category belonged to a different party (largest effective number of parties), and then taking the mean.

Consider the following example taken almost directly from Taagepera (1997, 150):

Proceed as follows:

|

|---|

3. Now, recalculate enep using the minimum found in Step 2: enepmin = 0.26+0.02= 3.571.

4. Finally, take the mean of enepomit and enepmin: enep1=3.847+3.571 2 = 3.71.

Treating independents and ‘others’ as a single party can be misleading, though, especially when these cat-egories are large. As a result, it may be preferable to use a “corrected” effective number of parliamentary parties based on the methods of bounds suggested by Taagepera (1997). This is enpp1 in our data set. To see how this is calculated, see the example with respect to electoral parties.

Effective Number of Presidential Candidates: The effective number of presidential candidates is calcu-lated as

Electoral Tier: An electoral tier is a level at which votes are translated into seats. The lowest tier is the district or constituency level. Higher tiers are constituted by grouping together different lower tier con-stituencies; they are typically at the regional or national level.

Fusion Mixed Electoral System: There are five subcategories of mixed electoral systems. Coexistence, superposition, and fusion systems are independent mixed systems, while correction and conditional systems are dependent mixed systems. A fusion system is one in which majoritarian and proportional formulas are used within a single district. As an example, Turkey used a fusion system in its 1987 legislative elections –