BSBMGT801 Development Of A Knowledge Management Strategy Sample Assignment

BSBMGT801 Direct the development of a knowledge management strategy for a business

Learner’s Guide

(Disclaimer: This study guide has been prepared just to provide an overall guidance to the Assignment. Many of the materials are directly copied from various sources which are duly acknowledged. If at any point in time that you are required to quote these materials provided here, you are required to acknowledge the original source. The college shall not be responsible for any copy right infringement.)

(Note: The material provided here should not be used for any income generation purposes. Sale or hire of this material should follow due diligence and proper procedure. If at any point of time, if this material is found used for income generation, such will be dealt in accordance to the country’s law)

1. Analyse existing knowledge management systems

The ability to manage knowledge is crucial in today’s knowledge economy. The creation and diffusion of knowledge have become increasingly important factors in competitiveness. More and more, knowledge is being thought of as a valuable commodity that is embedded in products (especially high-technology products) and embedded in the tacit knowledge of highly mobile employees. While knowledge is increasingly being viewed as a commodity or intellectual asset, there are some paradoxical characteristics of knowledge that are radically different from other valuable commodities. These knowledge characteristics include the following:

- Using knowledge does not consume it.

- Transferring knowledge does not result in losing it.

- Knowledge is abundant, but the ability to use it is scarce.

- Much of an organisation’s valuable knowledge walks out the door at the end of the day.

1.1 Evaluate existing arrangements for the capture and use of business knowledge from internal and external sources

Knowledge and knowledge management

In today’s economy more and more organisations are realizing that to acquire and maintain their competitive advantage they must explicitly manage their cognitive resources. For this reason, managers need to understand how they can identify and evaluate existing knowledge assets within the organisation and how to manage these assets in order to achieve the competitive advantage. However, many organisations frequently embark on knowledge management initiatives without a clear idea of what business knowledge they should have and what benefit they could expect.

Let’s look at a simple working definition of knowledge.

Knowledge has two basic definitions of interest. The first pertains to a defined body of information. Depending on the definition, the body of information might consist of facts, opinions, ideas, theories, principles, and models (or other frameworks). Clearly, other categories are possible, too. Subject matter, for example, chemistry, mathematics, etc. are few possible examples of knowledge. Knowledge also refers to a person’s state of being with respect to some body of information. These states include ignorance, awareness, familiarity, understanding, facility, and so on.

Knowledge management (KM), on the other hand, is the process of gathering, managing and sharing employees' knowledge capital throughout the organisation. Knowledge sharing throughout the organisation enhances existing organisational business processes, introduces more efficient and effective business processes and removes redundant processes. It is a discipline that promotes a collaborative and integrated approach to the creation, capture, organisation access and use of an enterprise's knowledge assets. KM has now become a mainstream priority for companies of all sizes.

Capturing a company's most valuable knowledge (asset) and distributing it effectively across the enterprise is a critical business issue for many help desk, customer support and IT departments.

In the knowledge economy, if company wants to be successful and gain its competitive advantage, it is necessary to constantly increase its value with the knowledge, which the company possesses. An organisation’s potential in creating the knowledge in the form of added value for its customers, employees, contractors, investors and other stakeholders in the knowledge economy depends on two elements. Frist element is the level of services which company provides and intensity of use of companies’ knowledge and the second element is the level in which company uses that knowledge in product production and services provision. If one organisation wants to be so called “Knowledge Management Company”, it is necessary to have following six basic competencies.

- Production ability. Many companies know only one thing to do - to produce products and provide services. Now, they have to do it with proper use of knowledge in appropriate structures and processes. So it means that companies, with effective use of knowledge, have to provide constant control of complex business processes, harmonization of suppliers’ network and the most effective and cheapest way for product to reach the final customers.

- Ability to make fast response. Large number of companies, which successfully keep their places in the top of competitive environment, believe that the key of their success lies in fast response to the changes and requirements of the market. One way to be able to respond properly is connection with customers’ needs and creation of business units, where every unit will cover specific segment of the market. These business units provide decentralization of authority, so every unit can faster bring decisions about how to react on changes on the market.

- Ability of prediction. If company wants to be truly successful it has to be capable to perceive business environment as whole picture and not only to respond to the trends, but also to predict them.

- Ability of creation. Companies constantly have to search for the new ways to maintain their competitive advantage. It depends on their ability to create knowledge and to create it on different ways by producing new products or technologies, using existing knowledge on the new manner or acquiring fresh knowledge about the clients.

- Ability of learning. The book “The fifth discipline” by Peter Senge popularizes concept of learning organisation. Learning organisation is the organisation that encourages continuous learning and knowledge generation on all levels and which developed ability for constant learning, adjustments and necessary changes. In that kind of organisation, employees manage the knowledge by the constant adoption and exchange of knowledge with each other. In learning organisation employees are ready to implement knowledge in making the decisions or doing business.

- Ability to last. Knowledge workers will have crucial role in knowledge economy.

Companies will have to adjust to the employees’ possibilities to require better work conditions and bigger autonomy. Firms will have to develop ways to revitalize and they will achieve that by constant update and regeneration of employees’ knowledge. Knowledge sharing in an organisation is the process of exchanging knowledge (skills, experience, and understanding) among various stakeholders in the organisations. Knowledge sharing is a tool that can be used to promote evidence-based practice and decision making, and also to promote exchange and dialogue among employees, employers, researchers, policymakers, and service providers. However, little is known about knowledge-sharing strategies and their effectiveness.

There are a number of possible reasons for why a coherent, integrated understanding of knowledge-sharing strategies does not yet exist:

- Knowledge sharing often occurs within and among diverse disciplines whose members may not communicate and share their expertise and promising practices.

- Knowledge sharing occurs even when sharing knowledge is not the objective; when informal knowledge sharing does occur, it may not be identified as a knowledge-sharing strategy.

- Knowledge sharing encompasses a broad scope of activities; lack of agreement on what “counts” as knowledge sharing limits collaboration and shared understanding. Knowledge sharing includes:

- Any activity that aims to share knowledge and expertise among researchers, policymakers, service providers, and other stakeholders to promote evidence-based practice and decision making.

- Situations in which knowledge sharing may not be an explicit goal, but knowledge and expertise are shared nonetheless.

The four business focus areas for KM include:

Operational excellence

This includes:

- Improving internal processes through application of knowledge

- Best practice development

- Process innovation

- Communities of practice

Customer knowledge

This includes:

- Building a better understanding of customers’ wants and needs and how to satisfy them

- Customer knowledge

- Market knowledge

- Product knowledge

Innovation

This includes:

- Creating new and better products

- Knowledge acquisition

- Knowledge development

- Reducing cycle time for new products

Growth and change

This includes:

- Replicating existing success in new markets or with new staff

- Defining and deploying good practice

- Bringing new staff up to speed quickly

Components of knowledge management

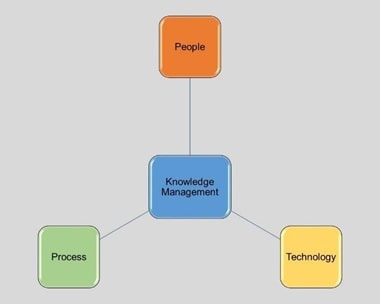

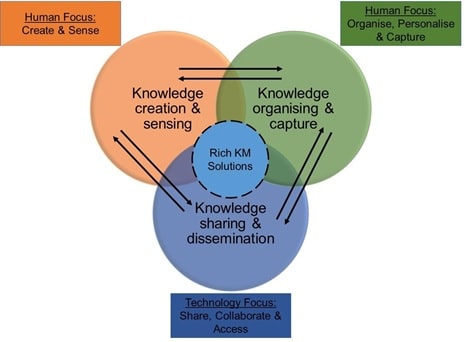

Based on actual experiences of the leading global KM case studies, the components for KM can be broadly categorized into three classes - People, Processes, and Technology, as shown in figure 1. While all three are critical to build a learning organisation and get business results from KM, a majority of organisations worldwide implementing KM have found it relatively easier to put technology and processes in place, whereas the "people" component has posed greater challenges.

The biggest challenge in KM is to ensure participation by the people or employees in the knowledge sharing, collaboration and re-use to achieve business results. In many organisations, this requires changing traditional mindsets and organisational culture from "knowledgehoarding" (to keep hidden or private) to "knowledge-sharing" (share among team members) and creating an atmosphere of trust. This is achieved through a combination of motivation / recognition and rewards, re-alignment of performance appraisal systems, and other measurement systems. A key to success in KM is to provide people visibility, recognition and credit as "experts" in their respective areas of specialization - while leveraging their expertise for business success.

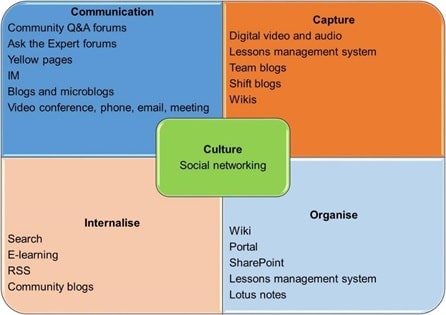

Figure 1: Components of Knowledge Management

The KM process component include standard processes for knowledge-contribution, content management (accepting content, maintaining quality, keeping content current, deleting or archiving content that is obsolete), retrieval, membership on communities of practice, implementation-projects based on knowledge-reuse, methodology and standard formats to document best-practices and case studies, etc. It is important for processes to be as clear and simple as possible and well understood by employees across the organisation.

Organisations also need to have proper systems in place to support knowledge-sharing, collaboration, workflow, document-management across the enterprise and beyond into the extended enterprise. For this, organisations typically provide a secure central space where employees, customers, partners and suppliers can exchange information, share knowledge and guide each other and the organisation to better decisions.

The most popular form of KM technology enablement is the Knowledge-Portal on the Corporate Intranet (and extranets where customers, partners and/or suppliers are involved). Common technologies used for knowledge portals include standard Microsoft technologies or Lotus Notes databases. A company must choose a technology option that meets its KM objectives and investment plan. While technology is a key enabler to KM, it is important to ensure that the technology solution does not take the focus away from business issues and is user-friendly and simple to use. Many companies have made the mistake of expending a disproportionately high portion of their KM effort and resources on technology – at the cost of people-involvement or strategic commitment - resulting in zero or very limited business results. It is also important to remember that users of the KM system are subject-matter experts in their respective areas of specialization and not necessarily IT experts.

Knowledge management assets and processes

Typically, there are six knowledge assets in an organisation, namely:

- Stakeholder relationships: includes licensing agreements; partnering agreements, contracts and distribution agreements.

- Human resources: skills, competence, commitment, motivation and loyalty of employees.

- Physical infrastructure: office layout and information and communication technology such as databases, e-mail and intranets.

- Culture: organisational values, employee networking and management philosophy.

- Practices and routines: formal or informal process manuals with rules and procedures and tacit rules, often refers to “the way things are done around here”.

- Intellectual Property: patents, copyrights, trademarks, brands, registered design and trade secrets.

Knowledge management processes maximize the value of knowledge assets through collaboration, discussions, and knowledge sharing. It also gives value to people’s contribution through awards and recognitions. Process includes generation, codification (making tacit knowledge explicit in the form of databases, rules and procedures), application, storing, mapping, sharing and transfer. Together these processes can be used to manage and grow an organisation’s intellectual capital.

Knowledge management is essentially about getting the right knowledge to the right person at the right time. This in itself may not seem so complex, but it implies a strong tie to corporate strategy, understanding of where and in what forms knowledge exists, creating processes that span organisational functions, and ensuring that initiatives are accepted and supported by organisational members. Knowledge management may also include new knowledge creation, or it may solely focus on knowledge sharing, storage, and refinement.

It is important to remember that knowledge management is not about managing knowledge for knowledge's sake. The overall objective is to create value and leverage and refine the firm's knowledge assets to meet organisational goals.

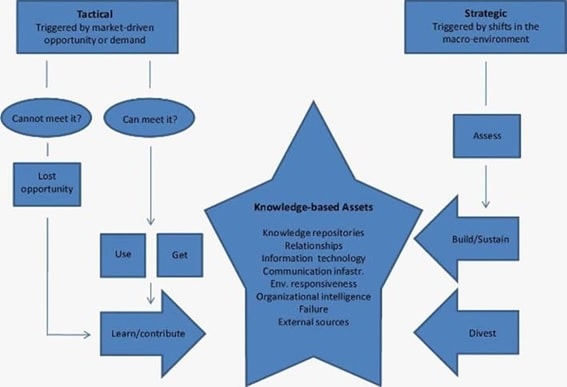

Figure 2: Dimensions of Knowledge Management

Implementing knowledge management, as shown in figure 2, thus has several dimensions including:

- Strategy: Knowledge management strategy must be dependent on corporate strategy. The objective is to manage, share, and create relevant knowledge assets that will help meet tactical and strategic requirements.

- Organisational culture: The organisational culture influences the way people interact, the context within which knowledge is created, the resistance they will have towards certain changes, and ultimately the way they share (or the way they do not share) knowledge.

- Organisational processes: The right processes, environments, and systems that enable KM to be implemented in the organisation.

- Management & leadership: KM requires competent and experienced leadership at all levels. There are a wide variety of KM-related roles that an organisation may or may not need to implement, including a CKO, knowledge managers, knowledge brokers and so on. More on this in the section on KM positions and roles.

- Technology: The systems, tools, and technologies that fit the organisation's requirements - properly designed and implemented.

- Politics: The long-term support to implement and sustain initiatives that involve virtually all organisational functions, which may be costly to implement (both from the perspective of time and money), and which often do not have a directly visible return on investment.

In the past, failed initiatives were often due to an excessive focus on primitive knowledge management tools and systems, at the expense of other areas. While it is still true that KM is about people and human interaction, KM systems have come a long way and have evolved from being an optional part of KM to a critical component. Today, such systems can allow for the capture of unstructured thoughts and ideas, can create virtual conferencing allowing close contact between people from different parts of the world, and so on.

Why KM?

Knowledge management, if used properly provides many benefits to organisations, as it is responsible for understanding:

- What the organisation knows.

- Where this knowledge is located, e.g. in the mind of a specific expert, a specific department, in old files, with a specific team, etc.

- In what form this knowledge is stored e.g. the minds of experts, on paper, etc.

- How to best transfer this knowledge to relevant people, so as to be able to take advantage of it or to ensure that it is not lost. E.g. setting up a mentoring relationship between experienced experts and new employees, implementing a document management system to provide access to key explicit knowledge.

- The need to methodically assess the organisation's actual know-how vs. the organisation's needs and to act accordingly, e.g. by hiring or firing, by promoting specific inhouse knowledge creation,

So, why is knowledge management useful? It is useful because it places a focus on knowledge as an actual asset, rather than as something intangible. In so doing, it enables the firm to better protect and exploit what it knows, and to improve and focus its knowledge development efforts to match its needs.

In other words:

- It helps firms learn from past mistakes and successes.

- It better exploits existing knowledge assets by re-deploying them in areas where the firm stands to gain something, e.g. using knowledge from one department to improve or create a product in another department, modifying knowledge from a past process to create a new solution, etc.

- It promotes a long term focus on developing the right competencies and skills and removing obsolete knowledge.

- It enhances the firm's ability to innovate.

- It enhances the firm's ability to protect its key knowledge and competencies from being lost or copied.

Unfortunately, KM is an area in which companies are often reluctant to invest because it can be expensive to implement properly, and it is extremely difficult to determine a specific ROI. Moreover KM is a concept the definition of which is not universally accepted, and for example within IT one often sees a much shallower, information-oriented approach. Particularly in the early days, this has led to many "KM" failures and these have tarnished the reputation of the subject as a whole.

1.2 Differentiate between knowledge management and information management systems within the organisation

Information Management vs. Knowledge Management

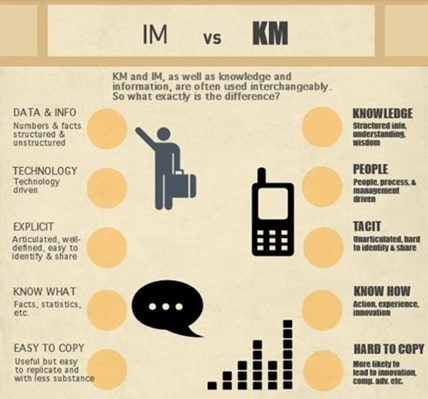

Most often knowledge and information are used interchangeably by many organisations and people. Therefore, you will often find KM solutions even today which are essentially nothing more than information or document management systems, i.e. which handle data, information, or perhaps even explicit knowledge, but which do not touch the most essential part of KM - tacit knowledge. Figure 3 below shows graphically the main differences between KM and IM with a short explanation below. IM in many ways is a useful tool for KM, in that information can help create and refine knowledge, but as a discipline it is a different one.

Figure 3: Information Management vs. Knowledge Management

The table below give the major differences between the IM and KM:

|

Information and IM |

Knowledge and KM |

|

Focus on data and information |

Focus on knowledge, understanding, and wisdom |

|

Deal with unstructured and structured facts and figures. |

Deal with both codified and unmodified knowledge. Unmodified knowledge - the most valuable type of knowledge - is found in the minds of practitioners and is unarticulated, context-based, and experience-based. |

|

Benefit greatly from technology, since the information being conveyed is already codified and in an easily transferrable form. |

Technology is useful, but KM's focus is on people and processes. The most valuable knowledge cannot effectively be (directly) transferred with technology, it must be passed on directly from person to person. |

|

Focus on organizing, analysing, and retrieving - again due to the codified nature of the information. |

Focus on locating, understanding, enabling, and encouraging - by creating environments, cultures, processes, etc. where knowledge is shared and created. |

|

Is largely about know-what, i.e. it offers a fact that you can then use to help create useful knowledge, but in itself that fact does not convey a Assignment of action (e.g. sales of product x are up 25% last quarter). |

Is largely about know-how, know-why, and know-who |

|

Is easy to copy - due to its codified and easily transferrable nature. |

Is hard to copy - at least regarding the tacit elements. The connection to experience and context makes tacit knowledge extremely difficult to copy. |

1.3 Ensure the effectiveness of existing procedures and systems is evaluated in terms of meeting the needs of clients, organisational aims, objectives and standards

Organisational knowledge resources

Business knowledge can exist on several different levels including the following:

- Individual: Personal, often tacit knowledge/know-how of some sort. It can also be explicit, but it must be individual in nature, e.g. a private notebook.

- Groups/community: Knowledge held in groups but not shared with the rest of the organisation. Companies usually consist of communities (most often informally created) which are linked together by common practice. These communities of practice may share common values, language, procedures, know-how, etc. They are a source of learning and a repository for tacit, explicit, and embedded knowledge.

- Structural: Embedded knowledge found in processes, culture, etc. This may be understood by many or very few members of the organisation. E.g. the knowledge embedded in the routines used by the army may not be known by the soldiers who follow these routines. At times, structural knowledge may be the remnant of past, otherwise long forgotten lessons, where the knowledge of this lesson exists exclusively in the process itself.

- Organisational: The definition of organisational knowledge is yet another concept that has very little consensus within literature. Variations include the extent to which the knowledge is spread within the organisation, as well as the actual make-up of this knowledge. It can be defined as "When group knowledge from several subunits or groups is combined and used to create new knowledge, the resulting tacit and explicit knowledge can be called organisational knowledge. "Organisational knowledge is all the knowledge resources within an organisation that can be realistically tapped by that organisation. It can therefore reside in individuals and groups, or exist at the organisational level.

- Extra-organisational: It can be defined as knowledge resources existing outside the organisation which could be used to enhance the performance of the organisation. They include explicit elements like publications, as well as tacit elements found in communities of practice that span beyond the organisation's borders.

In order to enhance organisational knowledge, KM must therefore be involved across the entire knowledge spectrum. It must help knowledge development at all levels and facilitate & promote its diffusion to individuals, groups, and/or across the entire firm, in accordance with the organisation's requirements. KM must manage organisational knowledge storage and retrieval capabilities, and create an environment conducive to learning and knowledge sharing. Similarly it must be involved in tapping external sources of knowledge whenever these are necessary for the development of the organisational knowledge resources.

To a large degree, KM is therefore dependent on the understanding and management of organisational learning, organisational memory, knowledge sharing, knowledge creation, and organisational culture.

The SECI Model

Nonaka and Takeuchi introduced the SECI model which has become the cornerstone of knowledge creation and transfer theory. They proposed four ways that knowledge types can be combined and converted, showing how knowledge is shared and created in the organisation. The model is based on the two types of knowledge – tacit and explicit knowledge.

Figure 4: The SECI Model

Socialization: Tacit to tacit. Knowledge is passed on through practice, guidance, imitation, and observation.

Socialisation consists in sharing tacit knowledge with others by way of mentoring (sharing internal knowledge, skills and insights). Tacit knowledge can be socialised by mentoring, imitation, observation and practice, all of which result in ‘shared knowledge’.

Externalisation: Tacit to explicit. This is deemed as a particularly difficult and often particularly important conversion mechanism. Tacit knowledge is codified into documents, manuals, etc. so that it can spread more easily through the organisation. Since tacit knowledge can be virtually impossible to codify, the extent of this knowledge conversion mechanism is debatable. The use of metaphor is cited as an important externalization mechanism.

Externalisation creates conceptual knowledge and is the process of converting tacit knowledge into explicit knowledge. Tacit knowledge is conceptualised through images or words; in this case, writing transforms tacit knowledge into an explicit form. This externalised mode of ‘knowledge conversion’ is produced as a result of a dialogue between people who transform tacit knowledge into explicit knowledge.

Combination: Explicit to explicit. This is the simplest form. Codified knowledge sources (e.g. documents) are combined to create new knowledge.

Combination is a mode of knowledge conversion which involves the combining of different types of explicit knowledge. This happens when people exchange knowledge, for instance via documents, telephone and meetings.

Internalization: Explicit to tacit. As explicit sources are used and learned, the knowledge is internalized, modifying the user's existing tacit knowledge.

Internalisation converts explicit knowledge into tacit knowledge. It consists in ‘learning by doing’, which is a process that occurs when the previous modes of knowledge conversion (socialisation, externalisation and combination), are internalised in people’s minds as tacit knowledge, which is represented by mental images or models.

1.4 Identify the need for improvements in the organisation's strategic use of knowledge

Developing a knowledge management strategy

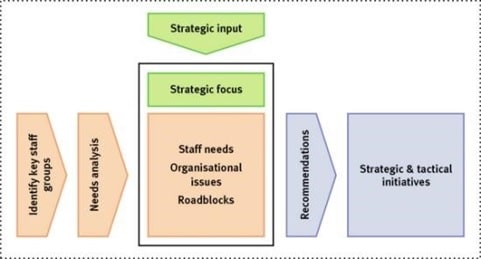

Organisations are facing ever-increasing challenges, brought on by marketplace pressures or the nature of the workplace. Many organisations are now looking to knowledge management (KM) to address these challenges. Such initiatives are often started with the development of a knowledge management strategy. To be successful, a KM strategy must do more than just outline high-level goals such as ‘become a knowledge-enabled organisation’. Instead, the strategy must identify the key needs and issues within the organisation, and provide a framework for addressing these.

Organisations need to have an approach for developing a KM strategy that focuses strongly on an initial needs analysis. Taking this approach ensures that any activities and initiatives are firmly grounded in the real needs and challenges confronting the organisation.

Organisational environment

Every organisation has a unique environment, defined by factors such as:

- purpose and activities of the organisation

- overall strategic direction

- organisational culture

- size of the organisation

- geographic spread

- staff skills and experience

- organisational history

- available resources

- marketplace factors

For this reason, each organisation has a unique set of needs and issues to be addressed by knowledge management. It is easy to jump into ‘solutions mode’, recommending approaches such as communities of practice, storytelling, content management systems, and much more. While these approaches may have widespread success in other organisations, they will only succeed in the current environment if they meet actual staff needs.

In practice, organisations are littered with well-meaning but poorly targeted knowledge management activities. In many cases, these failed because they simply didn’t address a clear, concrete and imperative problem within the organisation.

This is now recognised as one of the ‘critical success factors’ for knowledge management:

identify the needs within the organisation, and then design the activities accordingly.

The need for knowledge management

There are a number of common situations that are widely recognised as benefiting from knowledge management approaches. While they are not the only issues that can be tackled with KM techniques, it is useful to explore a number of these situations in order to provide a context for the development of a KM strategy.

These scenarios include:

- call centres

- front-line staff

- business managers

- ageing workforce

- supporting innovation

Beyond these typical situations, each organisation will have unique issues and problems to be overcome. Call centres

Call centres have increasingly become the main ‘public face’ for many organisations. This role is made more challenging by the expectations of customers that they can get the answers they need within minutes of ringing up.

Other challenges confront call centres, including

- high-pressure, closely-monitored environment

- high staff turnover

- costly and lengthy training for new staff

In this environment, the need for knowledge management is clear and immediate. Failure to address these issues impacts upon sales, public reputation or legal exposure.

Front-line staff

Beyond the call centre, many organisations have a wide range of front-line staff who interact with customers or members of the public. They may operate in the field, such as sales staff or maintenance crews; or be located at branches or behind front-desks.

In large organisations, these front-line staff are often very dispersed geographically, with limited communication channels to head office. Typically, there are also few mechanisms for sharing information between staff working in the same business area but different locations.

The challenge in the front-line environment is to ensure consistency, accuracy and repeatability.

Business managers

The volume of information available to business management has increased greatly. Known as

‘information overload’ or ‘info-glut’, the challenge is now to filter out the key information needed to support business decisions. The pace of organisational change is also increasing, as are the demands on the ‘people skills’ of management staff.

In this environment, there is a need for sound decision making. These decisions are enabled by accurate, complete and relevant information. Knowledge management can play a key role in supporting the information needs of management staff. It can also assist with the mentoring and coaching skills needed by modern managers.

Ageing workforce

The public sector is particularly confronted by the impacts of an aging workforce. Increasingly, private sector organisations are also recognising that this issue needs to be addressed if the continuity of business operations are to be maintained. Long-serving staff have a depth of knowledge that is relied upon by other staff, particularly in environments where little effort has been put into capturing or managing knowledge at an organisational level.

In this situation, the loss of these key staff can have a major impact upon the level of knowledge within the organisation. Knowledge management can assist by putting in place a structured mechanism for capturing or transferring this knowledge when staff retire.

Supporting innovation

Many organisations have now recognised the importance of innovation in ensuring long-term growth (and even survival). This is particularly true in fast-moving industry sectors such as IT, consulting, telecommunications and pharmaceuticals. Most organisations, however, are constructed to ensure consistency, repeatability and efficiency of current processes and products. Innovation is does not tend to sit comfortably with this type of focus, and organisations often need to look to unfamiliar techniques to encourage and drive innovation.

Stages in knowledge management

As well as giving consideration to different types of knowledge that need managing, organisations seem to be faced with other choices and dilemmas with regard to their overall knowledge management approach. There are four evolutionary stages in an organisation’s knowledge management approach:

- Reactive knowledge management – this is characterized by a narrow technical focus, typically as a reactive response to a specific external force.

- Mechanistic knowledge management – this is characterized by a strong emphasis on IT solutions and knowledge management practices that tend to be very top-down and prescriptive.

- Organic knowledge management – this is characterized by an emphasis on open and evolving structures and processes where there is a strong emphasis on the people aspects, including encouraging communities of practice and the use of support systems to reinforce knowledge sharing.

- Adaptive knowledge management – the adaptive knowledge management stage builds on the practices developed under the organic management approach, but here the structures are even more open and permeable. These characteristics, according to Ahmed et al, lead to an environment that is more open to experimentation: something that can enhance an organisation’s ability to adapt.

2. Evaluate knowledge management options

Managing knowledge involves the reuse and creation of relevant knowledge. Knowledge management (KM) is linked to the concept of organisational core competencies that can be defined as "the collective learning of the organisation, especially how to coordinate different production skills and integrate multiple streams of technologies". Generally, core competencies refer to the firm's primary expertise, which is a source of sustained competitive advantage. These are key capabilities, which, from the resource-based perspective of the firm, are the primary drivers of innovation and competitive advantage.

Core competencies thus have a large knowledge component, and managing them is, in the very least, a product of corporate strategy working with KM and innovation management. This simplified model has strategy dictating the overall direction, KM managing the knowledge dynamics, and innovation management turning core competencies into profitable core products. To understand the role of KM let us look at a brief overview of how core competencies are managed:

- Identifying and assessing core competencies: The firm should map out its key competencies, possibly linking them directly to specific core products. Then, an evaluation must take place, assessing what one has vs. what one needs to have (as determined by strategy and the competitive environment). KM is responsible for identifying where the key knowledge is located, including the tacit expertise and knowledge embedded in products, routines, etc., as well as identifying knowledge gaps.

- Sustaining core competencies: Organisational core competencies, like all knowledge assets, have the virtue of improving rather than depreciating through use. Conversely, lack of use will lead to erosion of any skill set. The role of KM here is twofold, on the one hand, it must keep stock of the state of key knowledge assets and, on the other hand, it must leverage key knowledge assets across the organisation.

- Building core competencies: Building new core competencies involves an interplay between knowledge, practice, coordination, and refinement. Knowledge assets must be built, enhanced, combined, and coordinated in an environment that supports experimentation and improvement. Building core competencies can be a complicated endeavour since sustained competitive advantage is derived from assets that are hard to imitate. From a KM perspective, this implies the build-up of specific tacit knowledge and expertise (i.e. uncodified knowledge that is generally more valuable, and inherently more difficult to copy and transfer), often across multiple departments or functions.

- Unlearning core competencies: Organisations have a habit of trying to keep doing what they have always been doing. Unlearning a competency when it is no longer useful is one of the key aspects of a successful firm, and history is riddled with examples of companies that have failed to do so. In the process of unlearning, KM again plays an important role by identifying and managing the firm's knowledge assets in the right direction. This may be done through re-training, restructuring, creating new knowledge flows, external knowledge acquisition, outright removal, etc.

It is important to understand that KM is not just a collection of individual initiatives. The buildup of skills and competencies, involving the coordination of multiple KM disciplines with other organisational functions, must often be managed according to long-term strategic goals and coordinated across the organisation.

2.1 Investigate barriers to capturing knowledge within the organisation

Knowledge management (KM) has become one of the key processes in today’s organisations as the payoff of an effective KM process is huge. When fully implemented, it provides a common KM system that is available to all stages in the product and/or service life cycle, improving decision making, reducing duplication of effort and rediscovery of knowledge, reducing costs, and empowering customers, users, and all of IT.

However, some organisations have not been able to implement KM successfully because of the following “barriers” that stand in their way:

- Failing to recognize that implementing KM is a strategic initiative, requiring time, acrossthe-board commitment from many people groups, and in fact, a change in the way the organisation works. This mandates the use of an organisation change model.

- Not taking a life cycle approach, but attempting to deploy KM as a tactical project, composed of a system and assigned resources. Since implementing KM is strategic in nature, potentially affecting the entire service and support organisation, it is critical that you take a life cycle approach to implementation.

- Failing to realize that there are organisational barriers due to silos that develop as a consequence of the way people are organized into discrete departments, reporting to different managers.

- Being too focused on KM tools, believing that the tool will deliver the value, rather than taking a strategic and process approach to KM implementation.

- Failing to make it easy to capture knowledge in the workflow, and in fact, requiring knowledge workers to take extra steps to format, capture, store, and share knowledge.

- Failing to build it into the way people work, so that knowledge sharing becomes a natural by-product of work. Not realizing that support for KM needs to be incorporated into policies and procedures, roles and responsibilities, supporting systems, metrics and reporting, appraisal processes, and reward and recognition.

These barriers can be overcome, however, with the right vision, strategies, and tactics. Let’s consider these barriers one by one and how to successfully overcome each to create a KM culture in your organisation.

The barriers in capturing knowledge within an organisation can be divided broadly into following three categories:

- Individual barriers

- Organisational barriers

- Technology barriers Individual barriers:

The distribution of the right knowledge from the right people to the right people at the right time is one of the biggest challenges in knowledge sharing. Barriers originating from individual behaviour or people’s perceptions and actions can relate to either individuals or groups within or between business functions. At the individual level, barriers are manifold and these barriers include:

- general lack of time to share knowledge, and time to identify colleagues in need of specific knowledge;

- apprehension of fear that sharing may reduce or jeopardise people’s job security;

- low awareness and realisation of the value and benefit of possessed knowledge to others;

- dominance in sharing explicit over tacit knowledge such as know-how and experience that requires hands-on learning, observation, dialogue and interactive problem solving;

- use of strong hierarchy, position-based status, and formal power (‘‘pull rank’’);

- insufficient capture, evaluation, feedback, communication, and tolerance of past mistakes that would enhance individual and organisational learning effects;

- differences in experience levels;

- lack of contact time and interaction between knowledge sources and recipients;

- poor verbal/written communication and interpersonal skills;

- age differences;

- gender differences;

- lack of social network;

- differences in education levels;

- taking ownership of intellectual property due to fear of not receiving just recognition and accreditation from managers and colleagues;

- lack of trust in people because they may misuse knowledge or take unjust credit for it;

- lack of trust in the accuracy and credibility of knowledge due to the source; and

- differences in national culture or ethnic background; and values and beliefs associated with it (language is part of this) Organisational barriers:

One of the key issues of sharing knowledge in an organisational context is related to the right corporate environment and conditions. The most common organisation-based barriers to knowledge sharing are:

- integration of km strategy and sharing initiatives into the company’s goals and strategic approach is missing or unclear;

- lack of leadership and managerial direction in terms of clearly communicating the benefits and values of knowledge sharing practices;

- shortage of formal and informal spaces to share, reflect and generate (new) knowledge;

- lack of a transparent rewards and recognition systems that would motivate people to share more of their knowledge;

- existing corporate culture does not provide sufficient support for sharing practices;

- knowledge retention of highly skilled and experienced staff is not a high priority;

- shortage of appropriate infrastructure supporting sharing practices;

- deficiency of company resources that would provide adequate sharing opportunities;

- external competitiveness within business units or functional areas and between subsidiaries can be high (e.g. not invented here syndrome);

- communication and knowledge flows are restricted into certain directions (e.g. top-down); physical work environment and layout of work areas restrict effective sharing practices;

- internal competitiveness within business units, functional areas, and subsidiaries can be high;

- hierarchical organisation structure inhibits or slows down most sharing practices; and

- size of business units often is not small enough and unmanageable to enhance contact and facilitate ease of sharing Technology barriers:

Knowledge sharing is as much a people and organisational issue as it is a technology challenge. There has to be necessary interactions between people and technology to facilitate effective knowledge sharing practices in organisations. The list below is of potential technology barriers to knowledge sharing:

- lack of integration of IT systems and processes impedes on the way people do things;

- lack of technical support (internal or external) and immediate maintenance of integrated IT systems obstructs work routines and communication flows;

- unrealistic expectations of employees as to what technology can do and cannot do;

- lack of compatibility between diverse IT systems and processes ;

- mismatch between individuals’ need requirements and integrated IT systems and processes restricts sharing practices;

- reluctance to use IT systems due to lack of familiarity and experience with them;

- lack of training regarding employee familiarisation of new IT systems and processes; and

- lack of communication and demonstration of all advantages of any new systems over existing ones

For companies to achieve continuous growth in their business, knowledge-management practices need to become an integral part of the day-to-day conversation. All companies face a number of knowledge sharing barriers that need to be dealt with to share knowledge more effectively to enhance companies’ overall market competitiveness and profitability. Ultimately, successful sharing goals and strategies must centre around a knowledge-sharing culture and depend on the synergy of three main factors:

- motivation, encouragement, and stimulation of individual employees to purposefully capture, disseminate, transfer, and apply existing and newly generated useful knowledge, especially tacit knowledge;

- flat and open organisational structures that facilitate transparent knowledge flows, processes and resources that provide a continuous learning organisational culture, clear communication of company goals and strategy linking knowledge sharing practices and benefits to them, and leaders who lead by example and provide clear directions and feedback processes; and

- modern technology that purposefully integrates mechanisms and systems thereby providing a suitable sharing platform accessible to all those in need of knowledge from diverse internal and external sources

2.2 Review evaluations and recommendations regarding knowledge management software with respect to its usefulness and likeliness to benefit the organisation

Knowledge Management Systems (KMS)

Knowledge management systems refer to any kind of IT system that stores and retrieves knowledge, improves collaboration, locates knowledge sources, mines repositories for hidden knowledge, captures and uses knowledge, or in some other way enhances the KM process. With proper implementation, IT systems have become a critical component of KM today. The most commonly used KM systems are:

- Groupware systems & KM 2.0

- The intranet and extranet

- Data warehousing, data mining, & OLAP

- Decision Support Systems

- Content management systems

- Document management systems

- Artificial intelligence tools

- Simulation tools

- Semantic networks

Problems and failure factors

Generally, the effects of technology on the organisation are not given enough thought prior to the introduction of a new system. Most of the organisations need to consider the two sets of knowledge necessary for the design and implementation of a knowledge management system:

- The technical programming and design know-how

- Organisational know-how based on the understanding of knowledge flows

The problem is that rarely are both these sets of knowledge known by a single person. Moreover, technology is rarely designed by the people who use it. Therefore, firms are faced with the issue of fit between IT systems and organisational practices, as well as with acceptance within organisational culture. It is also important for organisations to understand what knowledge management systems cannot do as introducing knowledge sharing technologies does not mean that experts will share knowledge.

There could be several other failure factors while using knowledge management software. These factors could include:

- Inadequate support: managerial and technical, during both implementation and use.

- Expecting that the technology is a KM solution in itself.

- Failure to understand exactly what the firm needs (whether technologically or otherwise).

- Not understanding the specific function and limitation of each individual system.

- Lack of organisational acceptance, and assuming that if you build it, they will come – lack of appropriate organisational culture.

- Inadequate quality measures (e.g. lack of content management).

- Lack of organisational/departmental/etc. fit - does it make working in the organisation easier? Is a system appropriate in one area of the firm but not another? Does it actually disrupt existing processes?

- Lack of understanding of knowledge dynamics and the inherent difficulty in transferring tacit knowledge with IT based systems (see segment on tacit knowledge under knowledge sharing).

- Lack of a separate budget.

Promoting acceptance and assimilation

The process of successful implementation of a knowledge management software has three stages: adoption, acceptance, and assimilation.

- Adoption:

- Influenced by design: Innovation characteristics, fit, expected results, communication characteristics.

- Not influenced by design: Environment, technological infrastructure, resources, and organisational characteristics.

- Acceptance

- Influenced by design: Effort expectancy, performance expectancy.

- Not influenced by design: Social influences, attitude towards technology use.

- Assimilation:

- Influenced by design: social system characteristics, process characteristics.

- Not influenced by design: Management characteristics, institutional characteristics.

Step 1: KMS adoption

Some of the key factors organisations need to identify while using KM software are: characteristics, commercial advantage, cultural values, information quality, organisational viability, and system quality. To promote KMS adoption organisations need to: Start with an internal analysis of the firm.

- Evaluate information/knowledge needs & flows, lines of communication, communities of practice, etc. These findings should form the basis of determining the systems needed to complement them.

- Make a thorough cost-benefit analysis, considering factors like size of firm, number of users, complexity of the system structure, frequency of use, upkeep & updating costs, security issues, training costs (including ensuring acceptance) etc. vs. improvements in performance, lower response time, lower costs (relative to the previous systems) etc.

- Evaluate existing work practices and determine how the KM systems will improve - and not hinder - the status quo.

Step 2: KMS acceptance

Some of the factors that need to be considered for KMS acceptance include: anxiety, ease of use, intrinsic motivation, job-fit, results demonstrability, and social factors. Promoting acceptance can be improved by:

- Involving the users in the design and implementation process when possible

- Involving the user in the evaluation of the system when applicable

- Making it as user friendly and as intuitive as possible

- Supporting multiple perspectives of the stored knowledge

- Providing adequate technical and managerial support

- Using product champions to promote the new systems throughout the organisation

Step 3: KMS assimilation

Some of the factors that affect KMS assimilation include: knowledge barrier, management championship, process cost, process quality, and promotion of collaboration. Assimilation can be improved by:

- Content management: In order for the system to remain useful, its content must be kept relevant through updating, revising, filtering, organisation, etc.

- Perceived attractiveness factors: This includes not only the advantages of using the KMS, but also of management's ability to convince users of these advantages.

- Proper budgeting: i.e. planning expenses and implementing a KMS that is cost efficient. Focus on collaboration.

- Management involvement: The system must be championed by management at all levels.

Naturally, these factors do not apply to all KM systems. Some are fairly straightforward and accepted in today's society (e.g. email). However, the strategic implications of implementing knowledge management systems that significantly aim to change the way things are done in the organisation requires proper consideration and careful planning. Moreover, with the evolution of systems to better support different facets of KM, they should be regarded as a critical component in the implementation of the discipline

2.3 Review investigations into incentives and reward systems to support knowledge management

There is no doubt that knowledge sharing has positive effect on organisational success and competitiveness. However, encouraging knowledge sharing is difficult. So, the managers and supervisors need to understand how to motivate employees to share their knowledge with colleagues and how to reward them for active knowledge sharing. This will not only help the managers design the effective reward system for knowledge sharing but also can lead to the understanding how to make the psychological contract between employee and organisation more explicit by underlining what the organisation expects from its employees and what it provides them in exchange for their knowledge sharing.

Reward systems are created in order to encourage employees to achieve organisational goals through proper performance and behaviour. Reward systems are often designed in many organisations to ensure proper knowledge sharing behaviour. Such reward system should be aligned with sharing in order to enhance knowledge sharing in organisations. Thus, it is important to explore what rewards should be used in order to directly or indirectly effect individual’s willingness to share knowledge and encourage his or her knowledge sharing behaviour.

The two main types of rewards that are used for rewarding knowledge sharing are intrinsic reward and extrinsic reward.

Extrinsic rewards are defined as tangible rewards that organisations give to her employees. Extrinsic rewards can take the form of various compensation such as salaries, bonuses, commissions, benefits, as well as other tangible benefits, for example, prizes, improved work environment, the opportunity to take part in the prestigious project, the opportunity to attain certain experts or communities of practice, the educational opportunity and so on.

Intrinsic rewards are psychological or internal rewards that employees get directly from performing the task itself. In the context of knowledge sharing intrinsic reward refers to the pleasure or satisfaction derived from knowledge sharing.

Extrinsic rewards for knowledge sharing can range from monetary or financial rewards such as increased salary and bonuses to non-monetary rewards such as recognition, promotion or job security. In practice, monetary rewards are often used for encouraging knowledge sharing among employees. However, in some cases employees may not be motivated by financial reward to share their knowledge. Also, in other cases non-monetary rewards, such as recognition or training can be more effective compared to financial rewards as employees also want their organisations to be appreciative of good work. Annual organisation awards, giving status for those who demonstrated the willingness to help others and so on may be used for this purpose.

The other aspect of reward system is related to whether the individual or team knowledge sharing behaviour is rewarded. Organisations can apply both individual-based and group-based reward systems. Individual-based reward is based on the individual contribution of valuable knowledge, and group-based reward is based on the contribution of the whole group through knowledge sharing to the firm performance.

Reward systems in the organisations may also differ due to different types of knowledge that is encouraged to be shared. When people were encouraged to share explicit knowledge, reward could be an effective strategy. In order to create the effective reward system for knowledge sharing, the reward system should be aligned both with the common organisational strategy and knowledge strategy.

The main intrinsic rewards which have significant positive effect on knowledge sharing among employees and can form the reward system are as follows:

- A sense of belonging and sharing common values. By sharing their knowledge with others individuals feel being connected and accepted within a team or entire organisation.

- A sense of achievement and success. By sharing their ideas and expertise during decision making or problem solving process individuals feel that they contribute to achievements and success of the team or the entire organisation.

- A sense of competence. By participating in knowledge sharing process individuals learn from others, gain new ideas and knowledge, increase their competence. By deepening their own understanding and knowledge they feel self-confidence and self-efficacy.

- A sense of usefulness. By mentoring, consulting, giving advice to others, employees fill enjoyment, satisfaction from meaningfulness of their help and usefulness of their knowledge and expertise.

- A sense of respect and recognition. By knowledge sharing employees earn recognition and respect from supervisors, peers and experts.

- A sense of trust. By receiving positive feedback from colleagues the individuals build self-confidence and confidence in peers. This increases a sense of trust in others and the belief that colleagues are ready to help them.

2.4 Ensure that the required processes for maintaining an integrated knowledge management system are considered

Organisations need to have specific steps, processes and procedure required to reach out to existing sources of knowledge. Also, the knowledge management initiatives supported by the management must have an impact on the economic measures of an organisation’s performance. Processes are also required to answer to the claims that outcomes of knowledge management initiatives are up to the desired standards.

Once the knowledge management practices and processes are in the place, the organisation can then seek to take a holistic view of related knowledge management practices needed to consistently drive benefits at all organisational levels.

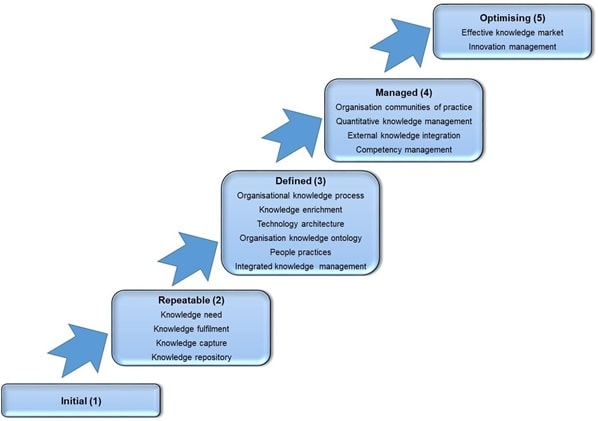

Figure 5 shows the key levels of KM process. These levels are discussed below.

Level 1 – The Initial Level

At the Initial Level, the organisation typically does not provide a stable environment for knowledge management. When an organisation lacks an approach to knowledge management, most of the knowledge related events are purely ad-hoc, and rely merely on individual initiatives. Prior knowledge and/or experience of KM is not available to the current domain, even if the problem may have already been encountered in the organisation. There are no formal structures for storage of knowledge in the project and the organisation. This translates to adhoc and variable performance of the team members in problem solving approach. The level of domain knowledge, technology knowledge, and process knowledge is ad-hoc and there are no systematic processes for storage, retrieval, and dissemination for knowledge in the projects. Success depends entirely on having an exceptional talent. The knowledge management capability of Level 1 organisations is unpredictable because the knowledge management process is ad hoc.

Figure 5: The levels of KM process

Level 2 – The Repeatable Level

At the Repeatable Level, the focus is on processes at the project level. The basic knowledge management practices for KM are established. There is a planned effort to define knowledge needs for a particular project and to seek specific knowledge at the beginning of the project. New projects make an attempt to include knowledge that has been created in organisation in other efforts. There is a commitment to apply the knowledge that has been located based on the defined knowledge needs in the project. Created knowledge artifacts are archived at the end of the project. A basic knowledge repository exists that collects all knowledge artifacts for the organisation. One objective in achieving Level 2 is to implement effective knowledge management processes at the project level, which allow organisations to apply successful knowledge derived on earlier projects, although the implementations by the projects may differ. The knowledge management capability of Level 2 organisations can be summarized as disciplined because knowledge need is defined, knowledge fulfilment is attempted, and knowledge is captured at a project level and stored in a knowledge repository for later use.

Level 3 – The Defined Level

At the Defined Level, the standard process for knowledge management practices across the organisation is documented at the project and the organisation level, and these processes are integrated into a coherent whole. Knowledge management practices at the project level are integrated into organisation-wide practices that provide underlying support to the usage of knowledge in projects. There is a group that is responsible for the organisation's knowledge management activities to coordinate organisation wide initiatives in knowledge management.

People practices are implemented to ensure that the staff and managers know how to apply knowledge management practices in different projects. Projects leverage the knowledge created in other parts of the organisation to apply, for solutions in their specific context. There is an assigned group to enrich the knowledge that is created in projects. There is formalism to ensuring that knowledge is periodically reviewed and enriched to maintain currency and reflect applicability. The capability of Level 3 organisations can be summarized as standard and consistent because knowledge management activities are stable and repeatable with a commitment to implement in a standard manner across all projects in the organisation. There is a well- defined support and focus on the organisation's part on the structures needed to implement knowledge management effectively at the project and the organisation level. This capability is based on a common, organisation-wide understanding of the activities, roles, and responsibilities in a defined process.

Level 4 – The Managed Level

At the Managed Level, the organisation sets quantitative goals for knowledge management. This is used to ensure that key measurements are in place to ensure that the business goals are met with the knowledge management practices. There is recognition that knowledge from external key constituents has a role to play. This could include information from customers, partners, and vendors involved in crafting a solution. Knowledge management practices from within the organisation are extended to key partners to ensure that greater knowledge benefits accrue. The organisation recognizes the role of communities of practice as the critical building block for building a knowledge culture and driving the enrichment and transfer of knowledge.

The process capability of Level 4 organisations can be summarized as managed with the communities of practice, external integration, and quantitative approach acting as the foundations for knowledge classification and dissemination.

Level 5 – The Optimising Level

At the Optimizing Level, the entire organisation is focused on continuous process improvement using knowledge management principles. The organisation drives a commitment to foster a knowledge market as the basis of knowledge exchange within an organisation, and derive all the benefits of effective practices. In addition, there is complete capability to manage shifts in innovation, and incorporate the innovations into the organisation in a systematic manner. The knowledge management framework forms the fundamental underpinnings of the organisation, which now has the capability to provide rapid solutions using existing expertise and solutions.

The process capability of Level 5 organisations can be characterized as continuously improving because Level 5 organisations are continuously striving to improve the range of their knowledge management capabilities. Improvement occurs both by consistent focus on creating knowledge markets and by incorporating new innovations.

Organisational roles and structure

It is important to express the practices in the KM systems consistently using terminology related to organisational structure and roles, which may differ from that followed by any specific organisation. A role is a unit of defined responsibilities that may be assumed by one or more individuals. The roles frequently used in the key practices are manager, senior manager, project manager, staff and individuals. The fundamental concepts of organisation, project, and group must be understood to properly interpret the key practices of the KM system.

A group consists of departments, managers, and individuals who have responsibility for a set of tasks or activities. Groups commonly referred to in KM system are described below:

- Knowledge Management Process Group: The knowledge management process group is responsible for definition, maintenance and improvement of knowledge processes used by the organisation. This group works towards the implementation of organisation and project level processes for knowledge management in an organisation.

- Knowledge Expert Groups: The knowledge expert groups are a set of groups that consist of experts in specific areas. The expert groups consist of one or more members who are designated and acknowledged as experts in a specific domain. Examples of areas of expertise include technology, process management, project management, or specific business domains. This group is responsible for enriching knowledge artifacts, and works towards enhancing the inherent knowledge within an organisation.

- Knowledge Ontology Group: The knowledge representation group works towards standardization in representation and interchange of knowledge in an organisation. This can be a dedicated group or a group that composes of domain experts with a knowledge representation coordinator to ensure that a standard definition of terms can be created and maintained in the organisation.

- Technology Group: The technology group is responsible for planning and implementing technology solutions to support the knowledge management program. This group is responsible for making choices on specific technology and tools that will best meet the needs of the organisation, and facilitate the implementation of these into the mainstream organisation.

2.5 Facilitate development of a business case to determine the viability of selected options and recommend a way forward for the organisation

Traditional memory is associated with the individual's ability to acquire, retain, and retrieve knowledge. Within business this concept is extended beyond the individual, and organisational memory therefore refers to the collective ability to store and retrieve knowledge and information. This includes the more formal records, as well as tacit and embedded knowledge located in people, organisational culture, and processes. There can be a number of stages in the organisational memory process. These include:

- Acquisition: Organisational memory consists of the accumulated information regarding past decisions. This information is not centrally stored, but rather it is split across different retention facilities. Each time a decision is made and the consequences are evaluated, some information is added to the organisational memory.

- Retention: Past experiences can be retained in any of the five different repositories:

- Individuals

- Culture: The language and frameworks that exist within an organisation and form shared interpretations.

- Transformations: The procedures and formalized systems that the organisation employs. These systems reflect the firm's past experiences and are repositories for embedded knowledge.

- Structures: These link the individual to other individuals and to the environment. Social interaction is conditioned by mutual expectations between individuals based on their roles within the organisation. The interaction sequences for a pattern over time and begin to extend to an organisational level. This can take place both through formal and informal structure and it constitutes a social memory which stores information about an organisation's perception of the environment.

- External activities: The surroundings of the organisation where knowledge and information can be stored. E.g. former employees, government bodies, competitors, etc.

- Retrieval: This can either be controlled or automatic. The latter refers to the intuitive and essentially effortless process of accessing organisational memory, usually as part of an established sequence of action. Controlled refers to the deliberate attempt to access stored knowledge.

The three stages are essential to the learning process of an organisation so as to determine the viability of selected KM options. This will also help the organisation to move forward utilising the knowledge being acquired. Much like an individual, the firm must be able to access and use past experiences so as to avoid repeating mistakes and to exploit valuable knowledge. Unlike an individual however, organisational knowledge is not centrally stored and resides throughout the firm and even beyond it. The process of retrieving knowledge/information will inevitably vary depending on the retention facility that one is trying to access. For example, written documentation may be accessed through IT while cultural memory is accessed through the understanding and/or application of the norms and procedures of the working environment.

Organisations can utilise knowledge management as a strategy to move forward. For this, organisations need to focus on the following aspects:

- Goals

- Knowledge enrichment techniques for the organisation are developed and maintained.

- Knowledge artifacts captured as part of projects are collected, reviewed, and used in the knowledge enrichment for the organisation.

- Certain activities have defined participation by knowledge experts.

- Affected groups and individuals agree to their commitments related to knowledge enrichment related activities.

- Commitment to perform

- The organisation establishes a set of groups that are designated to be responsible for the knowledge enrichment of the organisation. Such groups will typically be a set of knowledge expert groups, with specific expertise in the areas where knowledge enrichment is aligned to the business of the company.

- The organisation follows a written policy for enrichment of knowledge. This will be part of the organisation’s standard knowledge management process. This will take into account the fact that knowledge is captured as part of projects and enrichment of the captured knowledge will be coordinated and managed by the knowledge expert group. There is a documented approach for enrichment of knowledge.

- Senior management does a periodic check to review the knowledge enrichment practices and ensure that this meets the business goals of the organisation. Senior management takes the direct responsibility for establishing knowledge expert groups aligned with the business needs. Senior management does a periodic review of the work products produced by the knowledge expert groups in the knowledge repository as it relates to fulfilment of knowledge needs in an organisation.

- Ability to perform

- Adequate resources are assigned to ensure that knowledge enrichment takes place in the organisation. This includes the knowledge experts that are responsible for enriching the knowledge that has been created in the project. Knowledge experts will have the designated authority to participate in knowledge related activities of a project related to their area of expertise.

- The manager and team members are trained in the role and need for knowledge experts in an organisation. The team members who have created the knowledge artifacts understand that they need to work with the knowledge experts to ensure that knowledge enrichment takes place.

- There is awareness of knowledge enrichment and its implied benefits across team members in the organisation. This training will be oriented to the overall benefits of knowledge enrichment for the organisation and the role of the project in such an activity.

- The knowledge expert group is responsible for conducting knowledge enrichment sessions. Their participation is to ensure that the organisation norms for different aspects of knowledge enrichment are followed. Activities performed

- There is a defined approach that is followed for enrichment of knowledge. This is part of the organisation standard knowledge management process. The approach includes the guidelines associated with knowledge enrichment. The responsibilities of the knowledge expert group in knowledge enrichment and the project team members are outlined. Information guidelines on the documentation regarding knowledge enrichment are included for different aspects of knowledge enrichment. Specific information is included on storage of the original and modified versions of the knowledge artifacts. The process of enrichment is managed and controlled.

- The timing of enrichment is planned and adhered to formally. Once the knowledge artifacts is captured within a project, there is a defined periodicity for the enrichment of knowledge. Knowledge experts will participate to assess and enrich the knowledge artifacts.

- Knowledge experts perform the enrichment of knowledge as per the defined norms for the organisation. Activities include one or more of the following:

- Provide assistance in defining the knowledge needs for a project based on the problem statement for the project.

- Providing knowledge artifacts and expertise to fulfil knowledge needs belonging to their area of expertise. Provide specific information and guidance on how existing artifacts can be modified to meet the needs of a specific project. In addition, knowledge experts may assist the project manager is estimating the effort, cost, and quality parameters of the organisation in using existing artifacts vis-à-vis developing the artifacts.

- Directing the project teams to review and use specific artifacts in the knowledge repository that may be applicable to fulfil a specific knowledge need. Knowledge experts may assist in the modification and adoption of existing artifacts by working with the project teams.

- Participating at knowledge capture at periodic intervals in the project. Activities include all aspects of knowledge enrichment including knowledge assessment, socialization, combination, internalization, externalization, abstraction, and modifications.

- Formal reviews are conducted to address the accomplishments of knowledge enrichment at periodic points by senior management. The knowledge management process group will conduct periodic reviews of knowledge enrichment processes and activities.

- Measurement and analysis

- Measurements are made to understand the status of the knowledge enrichment process. Examples of measurement include the number of artifacts that have been enriched, artifacts modified, tacit knowledge captured, cost and schedule for the knowledge expert group.

- Verifying implementation

- The activities of knowledge capture are reviewed with senior management on a periodic basis.

- The knowledge management process group conducts periodic reviews of to verify process conformance of the knowledge enrichment process.

3. Develop a knowledge-management strategy

Organisational learning

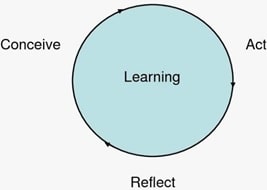

Organisational learning is the way organisations create new knowledge and improve their performance. Botha et al. describe the organisational learning process as follows:

Figure 6: The organisational learning process

As we can see in figure 6, organisational learning is based on applying knowledge for a purpose and learning from the process and from the outcome. Organisational learning can be seen as "the bridge between working and innovating." This once again links learning to action, but it also implies useful improvement.

The implications to knowledge management are three-fold:

- One must understand how to create the ideal organisational learning environment One must be aware of how and why something has been learned.

- One must try to ensure that the learning that takes place is useful to the organisation

Organisational learning theory: Company perspective

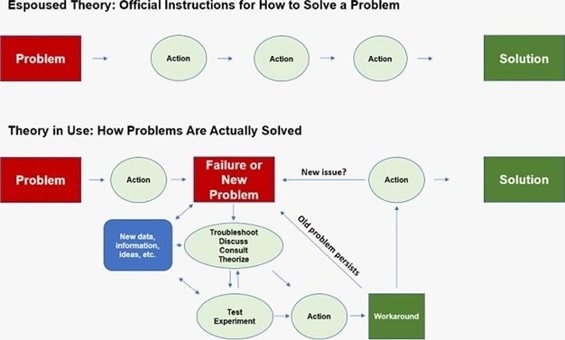

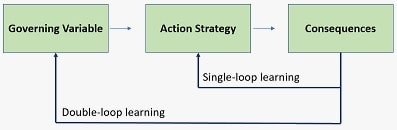

Two of the most noteworthy contributors to the field of organisational learning theory have been Chris Argrys and Donald Schon. Organisational learning (OL), according to Argrys & Schon is a product of organisational inquiry. This means that whenever expected outcome differs from actual outcome, an individual (or group) will engage in inquiry to understand and, if necessary, solve this inconsistency. In the process of organisational inquiry, the individual will interact with other members of the organisation and learning will take place. Learning is therefore a direct product of this interaction.

Argrys and Schon emphasize that this interaction often goes well beyond defined organisational rules and procedures. Their approach to organisational learning theory is based on the understanding of two (often conflicting) modes of operation: