The Market Opportunity Sample Assignment

2. The Market Opportunity

COMPETITORS IN A BROAD PRODUCT‐MARKET

These four competitors are all focused on the same broad product‐market. The broad product‐market consists of businesses and final consumers in who have an interest in virtual meeting platforms (VMP).

Each of the VMP firms has focused on developing a platform to meet online with audio and video conferencing platforms and the best collaboration software. Since your firm is so heavily involved in this area, let's take a closer look at what needs are met by virtual meeting platforms.

Benefits Offered by Virtual Meetings Recognition Platforms

Advances in technology means that reliable video conferencing has become accessible and affordable, and can easily serve the modern workplace.

This has become important for a wide range of reasons, not least to empower employee flexibility to work remotely from home, businesses having multiple office locations, but also the increasing likelihood that key clients and partners are more likely to be based around the world.

With the right computer support, a VMP offers many powerful capabilities that translate to benefits for users. There are, however, some disadvantages to VMP. Some people still have trouble learning about the basic operation of a VMP. For example, the platform must be "trained" to recognize special virtual meetings features from each user. Further, for many people, using VMP’s is a really new idea and requires them to think in new ways. Thus, learning how to use specific VMP capabilities takes time—and may require special training. Even an experienced user can encounter problems.

For example, with an incorrect instruction the computer application delete a recording if the ‘meeting’ (say for a multimedia presentation) before it has been saved for later use. Further, the combined cost of a powerful computer, software applications, and the VMP is high.

Some customers compare these front‐end costs (the investment in training and equipment) to the time and costs they can save later. For example, a company may be able to develop virtual reports or presentations that can then be used by many different salespeople in the field—so they can save time preparing sales presentations and sales calls. Other customers are not trying to save money—they just want to learn something new and have some fun.

Many users of the new VMP think that the benefits far outweigh the limitations. In fact, many people use their VMPs and computers primarily for one type or another of computer application. As a result, demand for VMPs is strong—and growth in the market is expected as more people learn about what VMPs can do.

Product‐Market Segments

In the beginning, no one was certain who would buy a VMP. So each VMP firm focused on designing a good general‐purpose platform. Each VMP firm tried to develop one marketing mix that would do a pretty good job of meeting the needs of different market segments. This approach seemed to make sense in the beginning. It resulted in target markets that were large enough to be profitable. Now, however, problems are surfacing, All four firms offer VMPs and have developed marketing mixes that are very similar. Although the number of potential customers has increased, competition is intense. There is a good opportunity to find profitable submarkets. VMPs produced by the four firms are purchased both by final consumers and by businesses. The variety of final users ranges from sophisticated power users to students. While some of these potential customers are using faster or more powerful computer equipment, the basic capabilities are the same. Conversely, it is also clear that some of their VMP needs are very different since potential customers focus on different applications/functions (i.e., benefits) within the broad set of capabilities. Market‐Views' research reveals that most potential customers in the broad product‐market can be classified into more homogeneous market segments. Market‐Views has identified six main segments. Each segment has a nickname—to make it easier to remember. A description of each segment is provided below.

The Modern Students

The modern students are University students who use a VMP to work on projects, other school‐related assignments, and to pursue their extracurricular interests, including communications with family and friends. This is encouraged by Universities that want to be seen as innovators in educational technology. They have made VMP technology a priority— in some cases even installing VMP wireless "receivers" on "networked" computers in computer labs, dorms, and classrooms so that a student can easily use his or her own VMP on the available computers. Many of the modern students can't afford to buy a powerful computer of their own—but they can use one of the many available on campus. Even with access to a free computer, they want an economical VMP of their own to access and control the information technology resource materials available to them. Economy is a major concern for this budget‐constrained segment.

Students in this segment often form user groups or informally share advice to help each other get the full benefits of a VMP—or to solve VMP problems. Many campuses also have computer support centres that answer questions about hardware and software, including VMP applications. With so much help available, students don't seem to be particularly worried about learning to use a VMP or about problems they might encounter. As one student put it, "help from my roommate is better than any tutorial." Modern students accounted for about 20 percent of VMP sales last year. The VRP is proving to be very popular on campuses— and this submarket will probably continue to grow for some time.

The Home Users

The home users segment contains a mix of households who use a simple VMP to do a variety of ’meetings’ such as catching up with family In some homes, people even use a VMP to leave each other messages. For example, rather than just leave a list of things that need to be done, they quickly dictate an "enhanced" message with all the relevant details and message it to another member of the family. Different members of the household may use the VMP for different reasons—but typically what they are doing is not very complicated given available technology. They're just having fun.

The home users are pretty much on their own‐so they prefer a platform that is easier to learn. They seem only moderately concerned about error protection, perhaps because their uses of a VMP are not for critical job‐related matters; on the other hand, they may become more sensitive about error protection over time if they make errors that waste a lot of time. Money for a VMP usually must come from some other area of the household budget—so most home users have only limited interest in high‐priced VMPs. Last year, the home users segment accounted for about 15 percent of total sales.

The Harried Assistants

The harried assistants segment consists of secretaries, administrative assistants and other employees who spend at least some setting up and managing virtual meetings. Without special VMP support, doing these jobs could be a massive headache and take a long time, but with a good VMP it's just becoming a normal part of the assistant's job. In fact, some companies have found that the same amount of work can be done by fewer assistants once they become skilled with a VMP. However, turnover in these jobs is high and often the assistants are just learning about a VMP—making the switch from preparing materials the old‐fashioned way. Thus, they want a platform that is not too hard to learn or use. Very quickly they must be able to use a VMP to prepare many routine assignments. Moreover, one assistant often needs to satisfy requests from a number of different bosses—so the harried assistants need a VMP that can handle a variety of needs. Most assistants worry about having difficulties with a VMP. They seem to have good reason to worry; bosses who themselves don't work with a VMP (or for that matter, even a computer!) are not very understanding when there is a problem.

Although the assistants may influence the choice of a particular VMP—others in the company usually make the final purchase decision. In addition, companies often purchase a number of VMPs at the same time—so that different assistants will be using the same platform. Last year, sales to this segment amounted to approximately 25 percent of total sales.

The Professional Creators

The professional creators segment consists of people who have professions in which they rely heavily on computers to create varied types of content materials—their "deliverable" output. For example, this group includes journalists and other types of writers, advertising agency people who create ad copy and images, package designers, and many others who have to communicate their creations and manage clients for a living.

Of all the segments, this group spends the most time using a computer and therefore the most time working with a VMP. Professional creators are often the innovators—among the first to use VMP capabilities. For example, a graphics designer might use a VMP in combination with relevant software applications to help communicate visual concepts into actual layouts and images "on the fly."

This work might include VMP created notes and annotation about what they are trying to accomplish. They would worry about final "polishing" later after they have initial feedback from a client. As this suggests, the professional creators are primarily concerned with speed and special features for advanced capabilities.

The right VMP helps them to be more creative more quickly—and by saving them time and producing a better product they can improve their earnings. Sales to this segment accounted for about 10 percent of last year's total sales.

The High‐Tech Managers

High‐tech managers buy a VMP primarily for their own use on the job. Usage tends to be higher when they are "on the road" (working with a laptop); at the office they often rely on an assistant to do routine computer work.

The managers use a VMP less than most users—but when traveling (and sometimes at the office), they use a VMP to make it easier and faster to do some special types of work themselves. For example, they might use a VMP during the evening in a hotel room to "whip out" a report that includes a complex spreadsheet—with fancy graphics—to highlight the results of a financial analysis.

Members of this segment are very interested in the number of capabilities offered. They take pride in the status of knowing about and using the very latest developments. Thus, their choices when purchasing a VMP are partially motivated by social needs for status and esteem. Some in this segment buy a VMP and learn to use it just because it's "in," not because it will make that much difference in their productivity.

The high‐tech managers pick the brand of VMP they want—but the company pays for it. Last year, sales to this segment accounted for nearly 22 percent of the total.

The Concerned Parents

The concerned parents are generally two‐career professional couples with school‐age children. These affluent—but busy—couples want to provide their kids with all of the advantages of high‐tech learning—and that includes making computing faster and easier.

They see VMP as an important trend for the future and want to get their kids interested in and experienced with it early. They also see a VMP as providing a valuable educational experience.

They want a simple VMP that children can learn and use themselves, Last year, the concerned parents accounted for 8 percent of total unit sales.

MARKET POTENTIAL

The Market Is Growing

The broad product‐market appears to be in the early middle part of the growth stage of the product life cycle (PLC). Industry experts think that growth in industry sales will continue for a number of years—perhaps for as much as a decade. Many experts believe that there is ample growth to fuel better profits for the whole industry—and for individual firms. However, even the optimists are unwilling to make precise forecasts too far into the future.

There is agreement, however, that the growth in market potential—what a whole segment might buy—will depend on several factors. These include the size of the segment, growth trends, the extent to which potential customers are aware of VMPs and what they can do, and how well the marketing mix (including customer service after the sale) meets customers' needs.

Some Segments Are Growing Faster than others

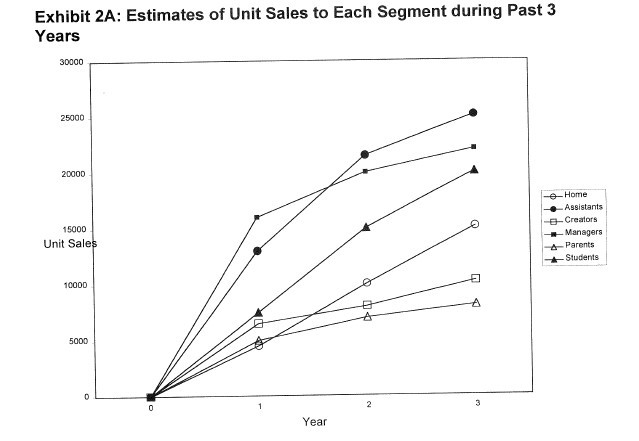

At present, the size of the various market segments differs substantially. Research found the Harried Assistants to be the largest segment with 25 percent of total unit sales last year. The concerned parents segment was the smallest with 8 percent. Current sales may provide a snapshot of the opportunity offered by each segment. However, sales to the different segments have grown at different rates. This can be seen in Exhibit 2A—which shows estimates of unit sales to each segment during the past three years.

Of Assignment, simply extending these trends could be dangerous—since factors behind the trends may change. In addition, these sales figures are estimates based on a marketing research survey of VMP users. Some people who responded to the survey couldn't recall exactly when they purchased the platform—so it is best not to view these figures as exact. Interpret Exhibit 2A with some caution. The large or fast‐growing segments—in terms of unit sales—may not be the best targets. Some segments may prove to be more profitable than others—depending on how much it costs to develop a marketing mix that will meet their needs and depending on the price they will pay. It may also be possible to develop a marketing mix that targets more than one segment in a combined target market.

Advertising May Make More Customers Aware

Industry experts agree that the overall level and nature of industry advertising will affect market growth. Many customers still are unfamiliar with virtual meeting platforms and what they do. Higher overall spending on advertising will help to inform more potential customers—and more of them are likely to enter the market. Because the life cycle is still in its growth stage, advertising so far has focused on building awareness and informing consumers about the product className.

Advertising that helps pioneer the market may help your own firm—but it may also help competitors. On the other hand, competitive advertising focused on specific brands may increase a firm's share of the market now and in the future—even if it does less to stimulate overall market growth.

Marketing Mix Must Meet Customers' Needs

It is important to emphasize that growth in the broad product‐market—or in segments of the market—will depend on how successfully available marketing mixes meet customers' needs. At present customers are buying a VMP that is not exactly what they want—they just purchase whatever is available that comes closest to their ideal.

On the other hand, many potential customers just wait. They will not buy anything until just the right product is available in the right place at the right price. Further, different segments have different needs. Thus, different marketing strategies—different marketing mixes for different target markets—may be required.

This last point is an important one—since the four firms in the market are at present all offering pretty much the same marketing mix.

TYPICAL MARKETING MIXES

Product

There can be many technical differences in VMPs, especially in how the "instruction set" software works. But research shows that most customers tend to simplify their evaluation process by grouping VMP features into three main areas:

(1) the number and variety of special features, (2) protection against user errors, and (3) ease of learning.

> Special Features

All VMPs offer many of the same basic features. Standard features provides audio and video conferencing, as well as screen sharing.

In addition to such standard features, a VMP may have a variety of more advanced feature "sets." These feature sets, generally referred to as "special features" tend to be specific to the varied types of software required for specific applications—ranging from database or spreadsheet applications to graphics/image programs to Internet browsers, smartphone friendliness and multiple device capabilities. For example, Mobile apps are provided separately for Android and iOS, \features to maximise call and image quality, one‐tap invites to join meetings, as well as chats, VoIP combined solutions, meeting analysis, transcripts, security and premium customer support

Not all VMP customers want a lot of special features. It doesn't help to have a VMP with a feature set that the customer doesn't want or need. Further, having more special features can also lead to errors. For example, using a feature in the wrong way, or in the wrong software application may produce undesirable results that are hard to change. Even so, users in certain target markets seem to have an appetite for special features that allow them to have virtual meetings control over more different aspects of their computing work.

> Error Protection

Some VMPs are designed to prevent users from accidentally doing something wrong. At first this may sound good—but there is a trade‐off. A VMP with more error protection is usually slower to use. For example, some users like a "conservative" VMP that protects them with an "are you sure" warning on the screen when it thinks they have issued a delete feature. But that warning slows things down. This time lag or interruptions between speaking and receiving a response can disrupt the natural flow of a conversation.

On the other hand, expert users are more precise and just want the VMP to execute the feature. All programs have some level of error protection. But, the extent of such error protection can vary substantially—and in total it affects how quick and convenient it is to use a VMP. In short, some people like a lot of error protection. Others think that defeats part of the benefit of a VMP and they prefer to do things faster.

> Ease of Learning

Another feature concerns how easy it is to learn to use a VMP and to train it to the user's unique usage patterns. Some customers are worried about how long it will take to get going— and how much help is available if there is a problem. Different aspects of the VMP maker's product may address this concern. The platform itself can be created to partially automate the "training" process so that it gets better at interpreting specific usage features. But, there are other approaches. VMP companies can provide Web based tutorials along with the platform—so the user can see how everything works. Others offer built‐in VMP‐based interactive training capabilities that lead a novice through each step of "training" the platform to recognize individual virtual meetings patterns.

Not everyone is interested in all of this. In fact, some may see it as a problem. A VMP that is designed to be easy to "train" may be less reliable if the VMP is later used in varying sound environments—say when there is background noise from a TV or air conditioning unit. Similarly, detailed tutorials are often paced too slowly and explain things the knowledgeable customer already knows, or make it take longer to find an answer. It is also true that a VMP that is easy to learn (early on) may also be more cumbersome to use (later on). For example, other things equal it is easier to learn how to use a VMP that has fewer capabilities.

But later, when the user knows all of the basics, it might be better to have more capabilities

(even if they were a bit more fuss to learn in the first place).

Product Modifications

Changes in technology as well as feedback and suggestions from customers mean that firms are continually doing research and development and updating and modifying their VMP products. In fact, all four firms in this market now have a yearly revision cycle that corresponds to updates in the underlying system. The start of each fiscal year brings announcements of new versions and models of VMPs in time for the dealer trade shows. In some instances, there may be major changes in the product features as firms attempt to better meet the needs of their target customers. In other cases only minor modifications are made to accommodate changes and additions to the system. In general, large changes in a single year tend to significantly stress the R&D department and require use of expensive overtime or contract programmers.

As part of the license agreement with the producer of the system, all four of the VMP firms must stick to some standards for the way a VMP converts its computer features. Thus, a person who has become familiar with one firm's VMP can usually switch to a new VMP from a competing company with very little hassle or "switching cost." Having a "standard" for the feature structure has helped the virtual meetings recognition industry grow, but there is also a potential downside, Specifically, consumers who are considering upgrading to a new model VMP product may not be hesitant to switch to a competing brand—if it does a better job of meeting their needs. In other words, each firm in this market must constantly "earn" the loyalty of its customers.

Place > Indirect Distribution

All four firms sell their VMPs through middlemen who in turn sell direct to final customers. Some of the middlemen focus on sales to business customers, and some of them focus on sales to final consumers. Thus, in a technical sense, some of them are wholesalers and some of them are retailers. Regardless of their primary customer focus, they all refer to themselves as dealers.

When VMPs were first introduced, several firms attempted to sell VMPs directly from their own websites as well as through dealers. This approach didn't generate many sales because most potential customers for VMPs in this early stage simply didn't believe that the platforms would deliver the benefits claimed. Some scepticism was justified; earlier software‐based virtual meetings recognition systems did not perform very well. In any event, most customers wanted to see a live demonstration of the product and have the opportunity to ask a salesperson specific questions. The full‐service dealers who had convenient locations, stock on hand, and knowledgeable sales reps met this need. However, as one irate dealer put it, "I'm not happy about having to compete with my own supplier for sales, especially given what I'm investing to create customers." Because of sentiments like this, many dealers dropped brands of VMPs that were being sold direct in favour of ones that were not. Rather than lose distribution, VMP firms that were selling from their own websites promised to replace the "buy now" button on their websites with a dealer‐locator feature. That was some time ago, but it's hard for them to go back on that promise now.

> Dual Distribution

Although firms that produce VMPs no longer sell direct to final customers, all four firms do currently rely on dual channels of distribution to reach the market. The two channels involve different types of dealers, and the different dealers tend to attract different types of customers.

> Full‐Service Dealers (Channel 1)

The dealers in one channel typically serve local customers with a carefully chosen line of virtual meeting and video conferencing solutions that they carry in stock. Some of these dealers are "independents" and some are part of a larger chain. Although many of them have some sort of website, they tend to focus on in‐store sales. The good ones have well‐trained salespeople who provide customers with technical information, demonstrations, and personalized service before and after the sale.

These dealers are especially attractive to customers who want to be able to see and compare different products—and to customers who want the assurance of having the supplier nearby in case of problems. In fact, the price these full‐service dealers charge usually includes a service agreement that extends the typical 90‐day warranty on a VMP platform to a full year and offers "same day" replacement if a VMP has a problem. This is attractive "insurance" to a user who routinely relies on a VMP,

It was these full‐service dealers who helped the VMP producers with the effort to pioneer the market and get early sales from sceptical customers. Thus, for convenience we will refer to them as Channel 1. In the early days these dealers were willing to handle the VMP because it was a new idea and it gave them a product that was distinctive relative to what was available from Internet or mail‐order discounters. At that time, the discounters focused on products that were already popular, would turn over fast without much personal selling effort, and didn't require much customer "hand‐holding."

> Discount Dealers (Channel 2)

However, as the market for VMPs grew, more online discount dealers became interested in carrying the VMP products. The dealers in this channel (Channel 2) offer more limited service and handle larger assortments of products. They also offer lower prices and tend to have more rigid policies concerning product returns; it can be a hassle for a customer to get a return merchandise authorization. If there is an after‐sale quality problem, they usually don't have their own service facilities so there are often delays in getting repairs.

For the bulk of their business, these discounters rely on orders placed on a website. These dealers are mainly order takers—they don't provide much service or help to customers. They can't demonstrate products for customers, and because of the very wide assortments of products they carry their salespeople often don't know the details of any of them very well. Rather, they primarily appeal to price‐sensitive customers as well as to customers who don't have a local supplier with the right selection.

> Distribution Intensity

At present, producers of VMPs are in general not attempting to obtain intensive distribution (i.e., making their products available through all suitable and available dealers) in either channel. Rather, it appears that your firm and competitors are trying to sell through about 30 percent of the*available dealers in each channel. When VMPs were first introduced, the best hill‐service dealers were not willing to carry a brand unless the producer provided exclusive distribution agreements within the dealer's main geographic markets—at least for a two year introductory period. Some other dealers didn’t want to handle the platforms at all because their customers had been unhappy with software virtual meetings recognition products—and they projected that sales volume would be low. Now that the market is growing, however, more dealers are interested in handling the product. Further, having a brand of VMP more widely available might increase sales and market share—in part because it is more convenient to more customers and in part because of it is being pushed by more dealers.

On the other hand, there's no "free lunch" when it comes to increasing distribution intensity. For one thing, some dealers don't do a very good job or contribute much to sales volume, and dealing with them may require more expense and hassle (for example, additional sales reps to call on them, deal with problems, etc.). Further, the best dealers are now already handling some brand(s) of VMP; getting them to add another brand of VMP (or switch from one they already carry) is tough.

Another issue concerns competition among dealers. Many customers still want help in deciding what VMP to buy (or if to buy at all). Yet, dealers won't put as much effort into a brand that is available from many other competing dealers. The larger the number of dealers with the same product just encourages more price competition, thinner margins, and lower profits.

Trade promotion is also an issue. Specifically, if firms in the industry start to make more aggressive use of trade promotion, dealers will expect it and use it as a bargaining lever. If that happens, more sales promotion spending will become a requirement to keep a larger number of dealers actively selling a particular brand of VMP.

In short, the dealers in the two channels provide different marketing functions and tend to appeal to different types of customers. The different types of dealers also require different kinds of promotional attention from the VMP producers.

Promotion

Promotion blends in the VMP business include sales promotion, personal selling, and advertising. In addition, firms try to get publicity in computer magazines and other trade publications, and they try to encourage good word‐of‐mouth endorsements among consumers. VMP producers target most of their advertising toward final customers, but their personal selling and sales (trade) promotion efforts are targeted at the dealers.

> Personal Selling

Personal selling is important to VMP producers. Each firm maintains its own staff of trained sales representatives. These salespeople sell to the dealers who in turn sell to the final customer. To better serve the needs of the different dealers, the sales force specializes by channel. Thus, any one salesperson works either with the traditional dealers or with online discount dealers—but not both.

Sales representatives do a mix of selling and supporting tasks. Selling tasks involve getting orders from current dealers as well as developing new accounts. Selling tasks also include persuading dealers to put more emphasis on pushing the firm's brand (for example, with better personal selling effort of their own). The supporting tasks include explaining technical details, training the dealers' sales staffs, and keeping the dealers up‐to‐date on new developments— including changes in sales promotion deals available from the firm.

The percent of personal selling effort spent on support activities tends to vary with the amount of service that the dealers provide to their customers. Dealers that provide a lot of service and selling help to their customers in turn look for more support and training from the VMP producer(s) whose product they sell.

> Advertising

VMP producers advertise in many media—trade and computer magazines, publications such as Business Week and Newsweek, and even on television and radio. Internet banner ads that link to company websites are also widely used. Each VMP producer has its own website, and these sites promote the specific advantages of the firm's brand of VMP, provide "dealer finder" wizards, and other useful information.

Last year advertising expenditures by the four producers totalled $1 million, or an average of $250,000 per firm. Firms use various types of advertising depending on their objectives. These types may be grouped into the five categories summarized below:

Pioneering advertising works to build primary demand—or demand for the whole product category—rather than promoting a specific brand. In the past, this was an important type of advertising since consumers needed to become aware of the possibilities of VMPs. Even now, there's a very substantial untapped market of consumers who do not know about VMPs, what they do, or why someone might benefit by using one.

Direct competitive advertising attempts to build selective demand (and share of market) for a firm's own brand. Its focus is on features of the current model and the main objective is immediate buying action, with relatively less carryover to future years.

Indirect competitive advertising also attempts to build selective demand, but it tends to focus on influencing future purchases—so that when a customer is ready to buy, he or she will choose that brand.

Reminder advertising reinforces earlier promotion and merely tries to keep the brand's name before the consumer. It doesn't do much good if customers are not already familiar with the brand, but it can be quite efficient if the brand is already well known and has a following of satisfied customers.

Corporate (institutional) advertising focuses on promoting the overall firm rather than a specific product. Because firms in this industry have a single product at this point, corporate advertising has not been used much. Corporate ads that have been run have not had clear objectives. However, if firms in the industry introduce other products, this may change. Corporate ads might then focus on positioning themes that are effective for promoting some primary product but also producing favourable spill over for a firm's other product(s). This might be a way to build interest across products at lower cost.

> Sales Promotion

Sales promotion is a relatively new tool for the VMP producers. In fact, so far each of the four

VMP firms has turned to outside specialists to help plan sales promotions.

Dealers are the target of most of the sales promotion—which includes trade show presentations, special brochures, dealer sales contests, and a variety of "deals" to the trade. Deals seem to be quite popular. For example, a producer might offer a dealer additional products free with a purchase of a certain quantity.

The objective of these trade promotions is to encourage the dealer to carry and push a particular brand or to devote special attention to selling it. This has caused some concern among the VMP producers. Some think that sales promotion simply increases each firm's costs. They think that a firm that doesn't do sales promotion will lose market share—but that no one gains if everyone is offering basically the same types of promotion. In other words, promotions seem to impact a firm's market share—positively if it is the only firm running a promotion (or spends more on the promotion) or negatively if it is the only firm without a promotion. However, if everyone is offering trade promotions they may just increase costs without much real benefit to anyone, except the dealers.

Because the firms in this market have not been using sales promotion very long, it's too early to know if these concerns are valid. But sales promotion is often more effective in prompting short‐term responses than in building longer‐term brand insistence.

> Publicity and Word‐of‐Mouth

VMP firms in the industry have in general enjoyed favourable publicity—primarily coverage in computer magazines read by both dealers and final consumers. In general, the magazines provide reviews of updated models of the platform, and tout the advantages of whatever is different. Thus, the general effect of publicity has been favourable for the industry. However, a major consumer publication recently published ratings of the help that users of different brands of VMPs were able to get from customer service telephone lines and at support sections of websites. Unfortunately, the news was not all positive, and it hurt some firms' sales. The magazine gave low customer service ratings to several firms whose support did not keep pace with their growth in customers. This, coupled with negative word‐ofmouth, resulted in shifts in market share to companies that were offering the best customer service. To counter this, companies that had earned weak customer service ratings increased their spending on customer service. Now there is once again not much difference among firms in after‐the‐sale customer service. But, that may change if some firms try to use service as a basis for competitive advantage.

Customer service must be carefully managed; at a minimum the recent ratings published by the magazine call attention to firms that don't provide adequate service. On a more positive note, superior customer service probably translates to some increase in market share. However, the cost of providing customer service—like other expenses—must be covered in the price a VMP firm charges.

Price

Suggested retail list prices for VMPs have ranged from $150 to $400 depending on the features of the platform, the manufacturer, and the channel(s) in which it is distributed.

The VMP producer decides on a wholesale price at which to sell to the dealers, the dealers then decide what retail price to charge their customers. Thus, the producer can't actually control the price to the final customer. But this is not a significant problem. Dealers tend to stick to the same price‐setting approaches. Thus, the producer can get a pretty good idea what the price will be at the end of the channel.

> Dealers Set the Retail Price

Dealers typically set the retail price by using a customary mark‐up percent. The mark‐up percent is different in the two channels. The difference is in part due to differences in the amount of service provided by the dealers (including the after sale extended warranty) and differences in the quantities they sell. The customary mark‐up by dealers in Channel 1 is 50 percent. Dealers in Channel 2 use a 35 percent mark‐up. The formula for the mark‐up percent is:

Dealer mark‐up percent = (Retail selling price — Wholesale price) / (Retail selling price).

Note that these dealers figure mark‐up percentages are based on the retail selling price.

While the middlemen in the two channels rely on standard mark‐ups to determine their selling price, pricing by the VMP producers must be based on consideration of their costs and on estimates of the demand curve. There are several reasons why producers can't use a standard mark‐up percent. First, costs of producing the actual VMP platforms and documentation are small compared to the costs of product development. Second, the most profitable quantity may not be what would sell at a price based on a standard mark‐up percent.

The VMP producers do announce a suggested retail price. Dealers are not obligated to sell the software at that price, but it may be difficult for them to ask for more than that amount. However, they can quite easily charge a lower price. In fact, price cutting is common among the discount mail‐order houses. This is reflected in their lower mark‐up percent.

The discounters may cut the price even further if they have been offered a sales promotion deal of some sort by a producer. In effect, some of these deals lower the dealer's cost per product. In the discount channel, the dealers tend to pass along some of their savings to customers—in the form of a lower retail price, By contrast, most traditional dealers just view a deal from the producer as a way for them to make a higher profit per unit.

> Customer Price Perceptions

Consumer research suggests that most VMP customers have in mind a reference price—the retail price they expect to pay for a VMP. However, different VMP users tend to look at the retail price in different ways—and the reference price is not the same for everybody. Some people think that the price indicates the quality of the platform—and for them a higher reference price is better; they interpret a low price as a signal of low quality. Others believe that the price has little to do with the actual quality. Instead, they think of quality in terms of what fits their needs. And if they have a low reference price, a low price on the software is part of what will meet their needs.

CUSTOMER CHOICES AMONG BRANDS

It's difficult to pinpoint why some customers respond favourably to a marketing mix and others don't. But understanding the needs of the different segments and then seeing the different marketing mix possibilities will provide some insights.

Customers do look for products that have the features they want at the right price. But other factors also motivate purchase of a particular brand of software.

The amount of attention that a dealer devotes to the brand may make a difference too. Some customers are uncertain about what they want or may not know very much about the different brands available. A dealer's salesperson who is knowledgeable about a particular brand and able to demonstrate its features may be the deciding factor in completing the sale. Furthermore, some customers prefer to buy from the traditional dealers—and others prefer the discounters, perhaps because it's easier for them to find the product on the Internet than it is to go to a local store. Either way, a customer is more likely to buy a brand that is available from a preferred type of dealer.

Brand awareness is important too. Advertising helps make customers aware of a brand. A customer may insist on a familiar brand—but be indifferent to one that is unfamiliar.

CONCLUSION

This report reviews the current state of the broad market in which you compete. It explains how your firm got to where it is today. It discusses the nature of the competition you face. It also highlights a number of potential opportunities—by identifying more homogeneous market segments and providing information that may help in developing better marketing mixes to meet the needs of target markets.

As consultants, we have tried to provide an objective report. We have avoided the temptation to inject much personal opinion—but rather have focused on the facts. In closing, however, we have a few recommendations to share.

We think that you, as the new marketing manager, have a real opportunity to do a better job than your predecessor did in selecting a target market and blending the 4Ps. The current head‐to‐head competition gives no one a competitive advantage. It appears that each competitor has pretty much followed the others. No firm seems to be doing an especially effective job of differentiating its offering to provide superior customer value to some specific market segment(s).

It may also be time to take a broader look at the product‐market. Your firm now has a single product. There may be an opportunity to expand your product line to better meet the needs of the target market. In addition, your arrangement with the microchip producer allows you to develop a product that most other companies can't offer. Of Assignment, you might face competition from your three primary rivals who have similar arrangements with the microchip maker. But, even so, that is less competition than many producers of computer accessories face. Of Assignment, significant resources will be needed for your firm to develop any additional product—so any decision in that area will certainly need the approval of the firm's

President.

We hope that this report has been helpful. We wish you the best of success with your new responsibilities.

3. Marketing Department Responsibilities

Note: Before the previous marketing manager retired, the President asked him to summarize the marketing department's responsibilities—and review other relevant information that might be helpful to a new marketing manager. This chapter is the text of the memorandum prepared by the previous marketing manager.

INTRODUCTION

As marketing manager, you are in charge of planning marketing activities, implementing your plans, and controlling them. You play an important role in strategic planning—because you are heavily involved in matching the firm's resources to its market opportunities.

Much of your time will be spent developing a marketing plan. So this memo focuses on strategy decision areas that need to be included in your plan. But it also deals with implementing and controlling the plans you make. Objectives should set the Assignment of your planning, so that is a good place to start.

OBJECTIVES

Your basic objectives are to use the resources of the firm wisely to meet target customer needs and contribute to the firm's profit. The time period is important here. Building longterm profitability sometimes requires that you spend money that results in lower short‐term profits—or even losses. This does not mean that you can take losses lightly. Ultimately, the firm must earn profits to survive. And, if other competing firms continually earn higher profits, it may be difficult to attract investors and the resources the firm needs.

These objectives are general. You will want to set other, more specific objectives. That way, you will know when your marketing strategy is on Assignment— or if it needs to be changed.

Your objectives should be realistic. The firm does not have unlimited resources—and it doesn't make sense for the marketing department to develop a plan that requires money the firm doesn't have.

RESOURCES

The firm has many talented employees. This is important to you. It means that the virtual meetings control programmers, engineers, and designers can develop the products you think will meet customers' needs. The firm also has the equipment and facilities to produce and distribute the products. But there are limits to these resources—and how much you can spend on a marketing strategy.

To make certain that there is enough money to operate the firm, the President sets a budget for each department for each year. You get your budget before you develop your marketing plan for the next year.

The President has more money to spend when profits are good. So a successful marketing strategy will lead to a higher budget. But, don't expect the President to give you a budget equal to all of the profit you generate; after all, other areas need budgets too. Further, the President knows that you need enough money to do a good job even if profits have been down. In fact, the firm gets data from a trade association on marketing spending by competing firms. The President analyses this data—to be certain that you get a large enough budget to develop a competitive strategy. In general, I recommend that you spend all of the budget that is allocated to you. If you use the money wisely, you should be able to leverage your spending into even greater revenues But, don't spend foolishly just to use up the money; remember that expenses must be paid before profits start to accumulate!

Once in the past, the marketing department appealed to the President to increase the budget amount—because we thought we had a sensible way to spend the money. At that time, the President did not grant our request, but he said that he did appreciate the accompanying proposal that explained how we wanted to spend the money and the results expected. The President's memo indicated that he would take the budget matter under consideration and that we would be told if there was enough money to entertain special budget requests. The memo also said that the President was giving consideration to authorizing a discretionary reserve fund. If the President authorizes a reserve fund, you would be able to spend against that fund, save it to spend in a later period, or simply leave it for an emergency. At any rate, the President will let you know if anything changes on the budget front. Unless you hear something different, you should manage your spending so that it doesn't exceed your budget.

The firm has developed planning forms (and decision support software) that make this easy. Although budget planning is not difficult, it is important. Thus, additional information about specific budget expenses will be given later in this memo.

Remember that a smart strategy need not be a high‐cost strategy. Some target markets can be served well even with a low‐cost marketing mix. Others might require a costly marketing mix but still be profitable. The focus of the marketing department is not on the budget per se—but rather spending the budget to best match the available resources to market opportunities. That requires careful selection of target markets—and skilful blending of the marketing mix to improve the customer value offered You will be able to do a better job in these areas if you know the strategy decision areas over which you have control.

PRODUCT

The firm already has an established product—and a completely new product can't be developed and marketed without the President's authorization. But that doesn't mean that you can't modify the firm's established product to better meet the needs of target customers. To the contrary, it is likely that over time you will need to refine the product because changes in customer preferences and competitors offerings are likely to impact how satisfied customers are with your offering and what customer value it offers.

As marketing manager, you decide when and how product features should change. These decisions should be based on information about target market needs, costs of the features, and costs of changing those features. Obviously, what competitors are offering in the market is also relevant.

Features

You make decisions about three features that customers consider important: the number of special features, the level of error protection, and the ease of learning. After you specify the features, R&D takes over to create the product.

But there are limits. Technology limitations prevent developers of the virtual meetings recognition instruction set for the VMP from creating a platform with more than 20 special features. And no one wants a platform with fewer than five special features. A testing lab supported by our industry trade association has developed a standard rating for levels of error protection. The rating can be between 1 and 10—where 1 is very low on error protection and 10 is high. Similarly, there is an accepted 1 to 10 industry rating for ease of learning. Thus, you specify the features of your product by deciding on the number of special features (between 5 and 20) and the ratings (from 1 to 10) for the level of error protection and ease of learning.

Cost of R&D for Product Modification

The R&D people can in general modify the product quite quickly, within the limits discussed above. Further, experience shows that the number of special features and the level of error protection can be decreased without cost. But the cost of other R&D product modifications can be substantial—especially if large changes are required in a single planning period. Further, these R&D and new‐product development costs are charged to the marketing budget when they are incurred—so they must be considered in developing the marketing plan.

The cost accounting experts in the firm have figured out a simple and accurate way to estimate the R&D cost of modifying each feature. Their approach is summarized in the table below:

|

Estimating the R&D Costs for Product Modifications | |||

|

Cost to Change Level from Previous Period | |||

|

Feature |

Feasible Range |

To Decrease Level |

To Increase Level |

|

Special Features |

5‐20 |

no cost |

$8,000 x (change) x (change) |

|

Error Protection |

1‐10 |

no cost |

$5,000 x (change) x (change) |

|

Ease of Learning |

1‐10 |

$3,000 x (change) |

$3,000 x (change) x (change) |

In this table, the term change refers to the difference in the level of the feature from one period to the next. The total product modification cost is the sum of the costs to change individual features.

Let's consider an example. The table below shows the costs to modify a brand which in the previous period had 6 special features, an error protection rating of 4, and an ease of use rating of 3 to create a "new" brand with 8 special features, an error protection rating of 3, and an ease of learning rating of 5.

Example of R and D Product Modification costs

|

Feature |

Old Product |

New Product |

Change | |

|

Special commands |

6 |

8 |

+2 |

$8,000 x 2 X 2 =$32,000 |

|

Error protection |

4 |

3 |

‐1 |

No cost for decrease |

|

Ease of learning |

3 |

5 |

+2 |

$3,000 X 2 X 2 = $12,000 |

Thus, to make the changes described above the total product modification cost would be $32,000 + $0 + $12,000 = $44,000

Note that it costs more if R&D must make big changes in a short period of time. For example, to increase the number of Special Features from 6 to 10 in a single period would be $8,000 x 4 x 4 = $128,000. By contrast, to increase from 6 to 8 in one period and then increase from 8 to 10 in the following period would only be $64,000 (i.e., as shown in the table above, $32,000 for each period). Thus, it is wise to consider whether the added R&D costs to make really big changes in a short period of time are really justified, or if planning incremental changes over a longer period is more sensible. Unfortunately, there are no easy answers in this area. Sometimes the advantages of speed in giving the market what it wants justifies the expense, but that may depend on what kinds of changes competitors make, and how fast they make them.

Regardless of how big a product change you want to make, the cost of the R&D for the required product modification is charged to your budget in the period when the changes are made. Further, the total product modification cost stays the same regardless of how much you sell in that period. So, if you make a big, expensive change but the market reaction is unfavourable, you pay for your mistake not only with lost revenue but also with out‐of‐pocket R&D expense. The other side of the coin is that there is no product modification cost when there is no change in product features for a period. Even with no product modification there is still risk. You may lose customers and sales to a competitor with a new, improved product.

You can continue to modify your brand in the future if that is necessary to implement your strategy. However, product modification costs occur each time you change the product— even if the features are returned to the level of a previous year. For example, you might reduce the number of special features one year and then add them back the next year. Although the total number of features would be the same, there would be a cost to modify the design to include the features again.

All product modifications are completed before production for the year starts. Thus, all units sold during the period have the new features. This is another reason why it is so important to have your plan in by the deadline specified by the President. If the plan is late, there may not be time to modify the product before production begins.

Unit Production Cost

The production department reports that the level on each feature directly affects the unit production cost. Specifically,

Unit production cost = $4 x (Number of special features) + $3 x (Error protection rating) + $2 x (Ease of learning rating).

Thus, your unit cost can vary from $25 to $130 depending on the features of the brand. The cost of actually producing units is not charged to the marketing department budget. But production cost is certainly an important consideration. A product that is costly to produce may require a price that is too high for the target market. And customers may not want—or buy—a product with the wrong combination of features. Further, the cost of goods sold for the period—along with other expenses—is subtracted from sales revenue to arrive at profit contribution.

Experts in the production department have been studying ways to reduce production costs. In a report, they said that they may be able to achieve economies of scale as the firm's cumulative production quantity increases. Specifically, they estimated that they should be able to reduce unit production costs by about 3 percent for each additional 100,000 units the firm produces— although the savings might ultimately taper off. However, the potential cost savings depend on making changes in the production equipment, and the V.P. of production and the V.P. of finance are still debating the wisdom of purchasing the equipment. However, the President will make an announcement if the equipment is purchased. Unless there is such an announcement, you should continue to use the unit cost estimates overviewed above.

Customer Service

While our basic product is the platform we sell, many customers expect to be able to get after‐the‐sale customer service if they have a question. They think of the availability of technical help as part of the product they buy. So customer service seems to be an important issue. And the service level a firm provides is getting more attention in the press.

Firms that haven't handled it well have faced bad publicity, negative word‐of‐mouth among customers, and a backlash in sales. Some customers look to our website for customer support, and some call our customer service phone number. As is the practice of our competitors, we leave it to the customer to pay for the phone call to ask a question—so telephone line charges are not an expense. But the marketing department must decide how much money to spend on staff to support the customer service queries that come in via the website or over the telephone lines.

It appears that most customer service requests come from new customers— within the first year after they have purchased our VMP. And for the most part the questions are easy to answer. Thus, we have been able to staff the phones and website with part‐time employees whom we schedule to work when the requests and calls are heaviest; they can always turn the tough questions—or the real problems—over to one of the engineers or platform programmers.

At any rate, the money spent to support customer service comes out of the marketing department budget. It makes sense to take a careful look at spending in this area. A mistake may certainly hurt us; but it's not clear whether doing a really good job can help us.

PLACE

In developing your marketing plan, you must decide on the level of distribution intensity that you want in each channel of distribution. Operationally, you can think of distribution intensity as the percentage of available dealers in each channel that you want to stock and sell your software.

In an absolute sense, the level of distribution intensity (market exposure) in a channel may range from exclusive to selective to intensive—depending on the firm's marketing strategy. Exclusive distribution is selling through only one (or very few) dealers in each market—and implies that you would expect salespeople to call on a relatively small percentage of the available dealers in a channel. Selective distribution is selling through those dealers who will give your product special attention; it implies that the sales reps may call on a mid‐range percentage of the available dealers in a channel. And intensive distribution is selling through all responsible and suitable dealers in a channel, although as a practical matter it probably would be too difficult and expensive to achieve 100 percent coverage.

Because the dealers in the two channels are quite different, the level of distribution intensity in one channel has no direct influence on the level of distribution intensity in the other. Therefore you may want different levels of distribution intensity in the different channels. In fact, if you wish you can elect to stop selling in one of the channels. We've considered that in the past, but so far have not had time to study whether it might be a good idea.

In spite of the conflict that we created selling direct earlier, it does not appear that our move to distribute through two different channels has reopened that can of worms. To the contrary, the traditional full‐service dealers seem resolved to the fact that the Internet discounters have become a fact of life. So, instead of just discounting prices, full‐service dealers have worked to improve their service, warranty coverage, and take whatever other steps they can to differentiate the value they offer customers.

In your marketing plan, use a rating of 0 (i.e., zero percent of the dealers) if you don't want to use dealers in a certain channel at all. Otherwise, use a rating between the extremes of 1 percent of the dealers (extremely exclusive) and 100 percent of the dealers (extremely intensive) to indicate the distribution intensity level you desire. Because this "percentage of dealers" approach has been used in the firm for some time now, it is a concise way to summarize what type of distribution you're planning.

Keep in mind that the level of distribution intensity you desire for your strategy may not be achieved if it's not consistent with other parts of your strategy, including how you handle promotions.

PROMOTION Personal Selling

The sales force plays a key role in recruiting new dealers, getting orders from dealers, and providing them with support and training. Because of differences in dealers, sales reps specialize by channel.

The marketing manager is responsible for deciding how many sales reps the firm needs in total—and how many are assigned to each channel. This is an important strategy decision area. Decisions here must consider the distribution intensity level in each channel. Achieving intensive distribution typically requires more personal selling effort—more sales reps—than selective distribution. Similarly, selective distribution requires more sales reps than exclusive distribution. Too little sales coverage in channels will hurt sales and relations with dealers. Too much coverage might help sales some—but if the added sales don't justify the increased sales force costs it will hurt profits.

Personal selling salaries—$20,000 a year per rep—are charged to the marketing budget Each sales rep also earns 5 percent commission on all sales to dealers. Since the total commission amount varies with the quantity sold, sales commissions are not paid out of the marketing department budget. But they are an expense so they directly affect contribution to profit.

The commission percent is currently set by company policy—to keep sales compensation in line with pay for other jobs in the company. However, the director of the human resources department has acknowledged that the marketing department might be able to motivate sales reps better if it could set the commission rate. The reps also pay attention to commissions that other firms pay. We had a meeting with the President on this issue, and it is being considered. I assume that the President will let you know if marketing area responsibility in this area is to be expanded.

New sales reps can be hired as needed to expand the sales force. Beyond the $20,000 a year salary, there is no direct charge for hiring a new rep. However, in this company new reps spend about 20 percent of the first year in training. So, in the first year, they are only 80 percent as productive as an experienced rep.

You can fire sales reps (but not all of them) if you want to reduce the size of the sales force. But you must make firing decisions carefully. It disrupts a rep's life to lose his or her job. Furthermore, the company gives each fired rep $5,000 in severance pay, and the $5,000 must be paid from the marketing department budget.

Sometimes you can avoid hiring or firing by reassigning a rep from one channel to the other. There is no cost to reassign a rep, and because experienced reps seem to adjust to the new channel situation quickly, there is no real loss in selling effectiveness.

The President of our firm feels very strongly that sales reps play an important role in developing good long‐term relations with dealers. To ensure good relations with dealers, the President has instructed that sales reps spend 10 percent of their time on non‐selling or support activities, These activities include explaining the technical details of the product, training the dealers' salespeople, and generally building goodwill with the dealers. Clearly, firms that have ignored these support activities in the past have lost important dealers. Even so, it's hard to tell if 10 percent is the right allocation for support tasks.

Advertising

Advertising is used to inform customers about VMP capabilities and benefits in general. It's also used to promote the strengths of the firm's brand relative to competing brands. How much to spend on advertising is an important strategy decision. Advertising costs are paid from the marketing budget. The firm works with an advertising agency that helps develop the actual ads and works out the details of what media to use. The agency also has in‐house specialists who do a good job of leveraging advertising materials developed primarily for other media so that they can be used to enhance the promotional value of our website.

The ad agency argues that the amount spent on advertising impacts advertising effectiveness. However, the ad agency cannot say exactly how large a sales volume will result from a given advertising budget. This is because customers respond to the whole marketing mix, not just advertising. But the ad agency has provided some general guidelines.

First, advertising impact depends not only on your firm's level of advertising but also on what competitors spend on advertising. Very low levels of advertising— below some threshold level—will have little impact The advertising message will be lost among the clutter of competitors' ads. But, at the other extreme, there is an upper limit on the sales that advertising can generate. Money spent on advertising that approaches or exceeds that saturation level is wasted.

This is a dynamic market. Advertising has the greatest effect in the year it's done. But some benefit may carry over to the next year or future years. Advertising impact may also vary depending on the type of advertising that's done‐ The agency works with the firm to select the best type of advertising for the money available. Marketing department decisions in that area are usually based on what competitors are doing and on the stage in the product life cycle, as well as the objectives to be accomplished.

PRICE

Legal Environment

Price is an important strategy decision area. You set the wholesale price—the price paid by your dealers. At present, the legal department in the firm requires that you charge all dealers the same price. However, the firm's lawyers are studying the laws in this area. They think that it may be legal to charge a different wholesale price to dealers in the two channels since they provide different kinds of marketing functions. Until the lawyers decide, however, you must charge the same wholesale price in each channel.

Price Affects Demand

Dealers set the retail price—but you should consider the likely retail price when you set the wholesale price. The retail price will affect the quantity demanded by the target market. Some segments of the market are more price‐sensitive than others.

You can easily calculate the likely retail price because dealers use customary mark‐up percents‐—50 percent in Channel 1 and 35 percent in Channel 2. The way to do the calculation is:

(Likely) retail price = (Wholesale Price [A 100) / (100 — Mark‐up percent)

You are free to change the wholesale price from one year to the next. But substantial price changes from year to year may confuse customers and dealers.

Price Should Cover Costs

The revenue you earn is equal to the wholesale price times the quantity sold. The price should be high enough to cover unit production costs and leave enough to contribute to other expenses (including sales commissions) and profit. Planning is important here.

As discussed earlier, you can estimate unit production costs based on the product features you're planning. Other costs to consider are those that are charged to the marketing department budget. Most of these have been covered earlier. As a convenient summary, however, they are listed below:

Summary of Costs Charged to Marketing Department Budget

- Product modification costs (if any),

- Customer service costs,

- Sales force salaries and severance pay,

- Advertising expense, and

- Marketing research expense.

Marketing research expense depends on how many marketing research reports you buy.

Marketing research is covered next.

MARKETING RESEARCH

Marketing research can be an important source of information about your target market, how well your marketing plan is working, and what competitors are doing. Some marketing research information is available free from secondary sources—including reports in trades’ magazines, data available on the Internet, and studies by the industry trade associations. Much information is also available at no cost from the firm's marketing information system (MIS). In addition, an outside marketing research firm sells a variety of useful marketing research reports. Examples of the different reports are provided in the next chapter, but they are briefly described below.

Information Available at No Cost

> Industry Sales Report

Each year, the industry trade association compiles an Industry Sales Report and provides a copy to each firm in the industry. The report summarizes the total unit sales and the total (retail) dollar sales for each brand. It also reports the market shares for each firm based on both unit sales and dollar sales. Moreover, it gives total unit sales and total (retail) dollar sales for each distribution channel.

> Product Features and Prices Report

Sales reps are instructed to report back to the firm the features of all brands on the market and the retail price for each brand in each channel. This information is organized in the firm's marketing information system and is summarized at the end of the year in a Product Features and Prices Report.

> Marketing Activity Report

Over time, the market research department collects information about each competitor's promotion blend. Competitors try to keep their plans secret—so it's impossible to get this information in advance. However, much of it is quickly available from advertising media and trade associations, dealers, trade publications, and even competitors' websites and reports to stockholders. This information is compiled in the firm's MIS to produce the Marketing Activity Report. It includes summaries—for each firm—of spending on advertising, sales force size and commission rate, and any sales promotion activity.

This timely information is fairly accurate and thus gives an idea of what competitors are doing in the market.

Reports from an Outside Marketing Research Firm

An outside marketing research firm specializes in ongoing studies of the software market in which you compete. Results from its studies are summarized in six reports. The reports are available each year. But the marketing research firm requires advance payment. You can purchase any report or combination of reports. The costs for the different reports vary. The title of each report and its cost is listed in the table below.

A brief description of each report follows—and samples appear in the next chapter.

|

Costs of Different Marketing Research Reports | ||

|

Report Number |

Title of Report |

Cost |

|

1 |

Market Share by Segment (all brands) |

$15,000 |

|

2 |

Market Share by Channel (all brands) |

$12,000 |

|

3 |

Consumer Preference Assignment |

$30,000 |

|

4 |

Marketing Effectiveness Report |

$25,000 |

|

5 |

Sales by Segment by Channel (firm's brand) |

$15,000 |

|

6 |

Customer Shopping Habits Survey |

$7,000 |

> Market Share by Segment

This report gives the market shares (based on units sold) for each brand in each market segment. It also gives the total unit sales for each segment.

> Market Share by Channel

This report summarizes the market shares, based on units sold, for each brand in each distribution channel. The report also includes total unit sales for each channel.

> Consumer Preference Assignment

This study summarizes the results of a sample survey of actual and potential customers from the various market segments. Customers indicate their most preferred (or ideal) level for each product feature. The numbers in the report are the average values reported by members of each segment.

Although representative customers are surveyed, the sample estimates may not be exact for the whole population. The research firm says that the results are accurate to within 10 percent of the true values for the different market segments.

This report also gives a price range for each segment. This range merely indicates the prices that members of the different segments typically expect to pay for a VMP.

> Marketing Effectiveness Report

This report summarizes the results of survey research on the effectiveness of your customer service as well as your advertising and personal selling decisions—both in an absolute sense and relative to competitors.

One measure of advertising effectiveness IS the proportion of customers who are aware of your brand. This measure is reported as a Brand Awareness Index ranging from 0.0 to 1.0. A higher index indicates greater awareness (familiarity). In practice, however, an index greater than .9 is very rare.

There is also a measure based on the customer service the firm provides. It is reported as a percentage rating, where a lower percentage suggests lower satisfaction with the service provided. This firm‐specific measure can be compared with a measure of the average rating for the overall industry, which is also provided.

Additional indexes indicate the effectiveness of the firm's efforts in each of the channels of distribution. The marketing research firm develops the Sales Rep Workload Index by studying how sales reps spend their time and how well satisfied dealers are with the service they receive from a rep. An index of less than 100 percent indicates that sales reps can satisfactorily handle all their accounts and could potentially call on more dealers. On the other hand, an index that exceeds 100 percent indicates that sales reps are overloaded and are trying to call on more dealers than they can effectively service.

The Dealer Satisfaction Index is basically a summary measure of what dealers think about the quality and effectiveness of your sales force as well as any trade promotion assistance they receive. This index generally varies above and below 1.00. If it is less than 1.00, it suggests that dealers are not satisfied with some aspects of your promotion blend, at least relative to what competitors are doing If it is greater than 1.00, this may be an area of competitive advantage.

However, this advantage may be coming at the cost of greater spending on sales effort or promotion in the channel.

The Channel Strength ("Push") Index is basically a summary measure of the overall "push" that your brand gets in consumer purchase decisions from dealers in the channel of distribution. It takes into consideration the number of dealers who are carrying your brand and how much effort they are willing to put behind it—relative to competing brands. Like the Brand Awareness Index, the values on this index range between 0.0 and 1.00; however, in practice values over .80 are rare.

The research firm will not sell all of this detailed information for competing brands. But the report does provide some summary information. It gives the number of competitors with a lower index and the number of competitors with an index that is the same or greater. This report is expensive—but it does provide insights about your marketing strengths and weaknesses.

> Detailed Sales Analysis

This report details the number of units of your brand sold to each market segment through each channel. It can be very useful to see if the intended target market is buying the product— and, if so, from what dealers.

> Customer Shopping Habits Survey

This survey is used to determine the percentage of time that customers in the different segments shop in Channel 1 compared with Channel 2. The research is based on a sample of customers, and because of "sampling error" the results may not be exact for the whole population of customers. However, the market research firm says that the sample estimates are within 5 percent of the true values for the full population of customers.

Marketing Research—Benefits versus Costs

Much useful market research information is available. You should weigh the potential benefits of this information against the cost. Before deciding to buy a report, think about how you will use the information. Further, think about how the information can be used in combination with other data to give you additional insights. Advance planning for marketing research can lead to a more sensible use of your marketing budget.

FORECASTING DEMAND

It is the responsibility of the marketing department to forecast demand for the coming year. This forecast may be based on many different kinds of information—past sales trends, estimates of target market potential and growth, juries of executive judgment (for example, about what competitors are likely to do), and market research about customers' preferences. Of Assignment, the forecast must consider how well the marketing mix meets target customers' needs.

Developing a good forecast is important for several reasons. You will need a forecast of what you expect to sell to evaluate your marketing plan—to estimate expected revenues and profit/contribution. But there is an even more immediate reason. The production department uses the estimate of demand as a production order quantity. This is an important decision for marketing management.

The Production Order Quantity

Lead times to produce VMPs are short. As a result, the production department is able to increase production as much as 20 percent above your production order quantity to satisfy unexpected demand. It can also reduce the actual production quantity by up to 20 percent if the product does not sell as expected. This gives quite a bit of flexibility.