History Of Prehistoric And Mesopotamian Assignment Help

History of Art Culture and Architecture

In its first evolutionary stages, the pattern of mans existence was tribal and nomadic. Gathering vegetable food or hunting animals and moving from place to place in search of them, caves or natural shelters provided him with a home, which for the time being satisfied his primitive needs. Rather less than 10,000 years ago, he discovered the possibilities of agriculture, and from then onwards new factors were introduced into his life, which restricted his movements and resulted ultimately in the permanent settlements of a farming community. Under these circumstances individual homes acquired a new significance: the space in which certain domestic functions regularly took place needed to be enclosed and protected, and the craft of building was devised for this purpose.

Prehistoric And Mesopotamian

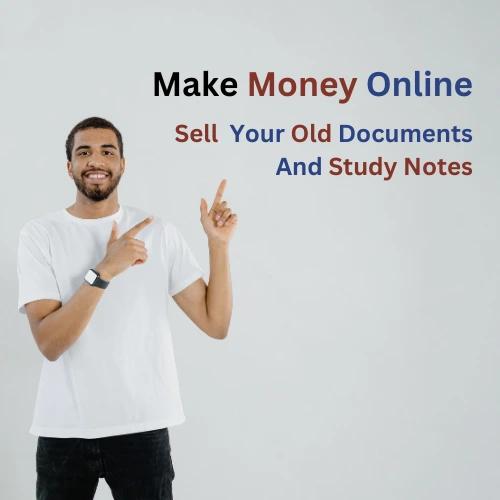

It was in the proto- and pre- Sumerian times that this idea seems effectively to have germinated. Then, in these settlements of southern Mesopotamia, amid a crescendo of creative invention, real architecture suddenly materialized as a setting for the complex functions of newly developed civilization. The earliest buildings here were of reeds and mud. Simply rectangular in plan but of an elaborate and ingenious construction, they must exactly have resembled the great mudhifs still built by the Marsh- Arabs of today; upright bundles of reeds with their heads bent together to form a vault, and a filling between them of mud-plastered wicker work. By Sumerian times these had long been abandoned in favour of more substantial brick buildings, but memory of their external appearance conditioned Sumerian design for many centuries to come, and the complicated pattern of their entrance facades survived both as a form of ornament and as the pictographic symbol of a temple. For already, in the middle of the third millennium B.C., temples and shrines were the buildings upon which the new-found faculty of architectural expression was mainly concentrated.

History Of Prehistoric And Mesopotamian Assignment Help By Online Tutoring and Guided Sessions from AssignmentHelp.Net

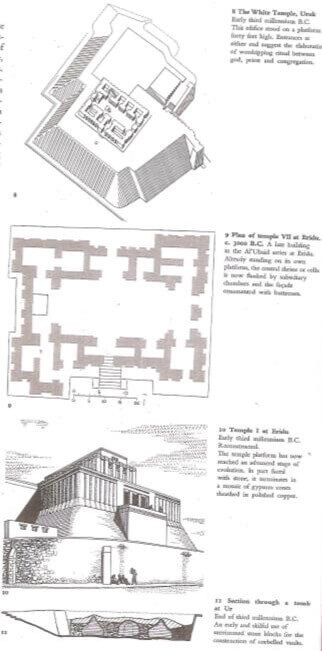

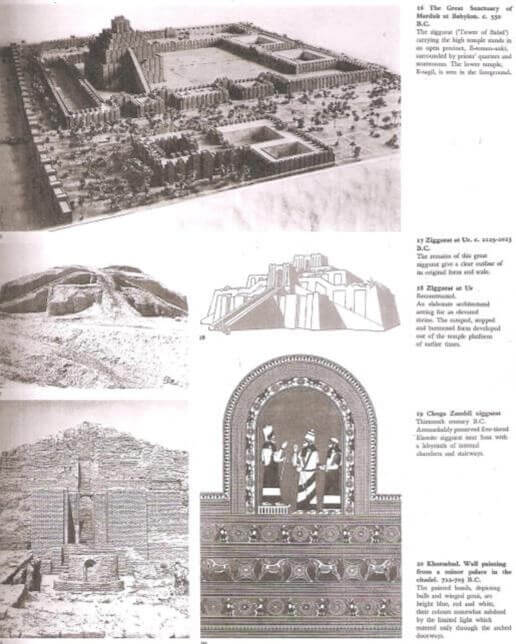

The idea of sublimating a religious ritual by elevating the shrine in which it took place, was one which persisted through Sumerian times and culminated in the high ziggurat towers of Babylon. At Eridu, the only Sumerian site where any stone seems to have been available, even more elaborate faade ornament was used in the latest prehistoric temple. Here, the ruins of earlier temples, were enclosed in a stone-faced retaining wall, and above this rose the serried bastions of the platform, ornamented in this case with bands of huge gypsum cones, their ends sheathed in polished copper. Fallen from the temple itself were found smaller cones chipped out of coloured stone and little rectangular cement bricks, perforated for the attachment of other architectural ornaments.

In discussing Mesopotamian architecture, it is religious buildings which monopolise ones attention. Far less care was lavished on secular construction, as may be judged, for instance, from the negligent design of an administrative building attached to a fine temple at Tell Asmar. Its only conventional feature is a rectangular throne- room or divan, approached on its short axis from a square open courtyard. Private houses too were of the introverted type, their rooms having no outward exposure, obtaining their light from a central court. With the flat facades of its fortifications relieved by alternative buttresses and recesses and punctuated by towered gateways, the general appearance of a typical Mesopotamian city is relatively easy to imagine. Flat roofs and the limitations of mud-brick construction restricted the possibilities of formal design, and, though little is actually known of parapet treatment or terminal ornament, the picture conceived is that of flattened prismatic elements rising tier above tier over an accumulation of earlier ruins, to where a group of religious buildings gain prominence from the vertical treatment of their facades, but are overshadowed by the rectilinear bulk of a ziggurat. Only these latter gave expression to the aspirations of a plain-dwelling people; for, like beacons in an otherwise featureless landscape, each tower must have been remotely visible to its neighbor.