Impact social media has in disaster communication

{`

AN EXAMINATION OF THE IMPACT SOCIAL MEDIA HAS

IN DISASTER COMMUNICATION

A Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment

Philosophy

Capella University

`}

CHAPTER1: INTRODUCTION

In the most recent decade, social media has been increasingly incorporated globally into the daily lives of people. It is defined as media that “consists of tools that enable the open, online exchange of information through conversation, interaction, and exchange of user-generated content” (Simon, Goldberg, & Adini, 2015, p. 611). Words unique to social media such as “social mention,” “tweet,” “hashtag,” and “post,” have entered the daily vocabulary of individuals in many nations.

Websites such as Facebook and Twitter are a growing part of many nation's conversations regarding politics, social life, economy, and emergencies. Social media platforms are often called social media tools and are taking an ever-growing role in disaster response (Reuter, Ludwig, Kaufhold, & Spielhofer, 2016). Initially, the main users of social media tools during disasters were ordinary citizens who supplied updates using various types of content. As of the date of this study, an important role in using social media to communicate with the public during disasters has included emergency responders, governmental agencies, and non-governmental organizations responsible for disaster relief (Reuter et al., 2016).

Various arguments exist concerning the utilization of social media platforms in disaster preparedness, response, and recovery. Although many organizations have adopted social media platforms, questions regarding their proper use remain. Even a prompt response can trigger a negative reaction from the public if the initiating organization fails to acknowledge the scope of the problem or cannot initiate the relief operations because of poor preparedness. Every organization has a unique approach to addressing these types of issues; however, the task remains of identifying the most effective media platforms to improve the quality of disaster communication and develop guidelines that will be accepted by the majority of governmental and non-governmental organizations. The purpose of this quantitative correlation study is to determine if, and to what extent, a statistically significant relationship existed between (a) EM professionals use of social media to share or exchange crisis information with other EM professionals and/or pertinent members of the community; (b) between the application of social media in disaster and risk communication and the following factors: usefulness, ease of use, personal innovativeness, advancement of the profession, access to peers, and barriers; and (c) EM demographic characteristics of age, gender, or location, and the use of social media platforms.

Background of the Problem

As the result of the increased adoption of social media tools by service agencies, social media platforms have brought significant change to communication behavior and communication practices. For example, a response to a disaster should be timely and informative. Over time, social media has become one of the primary tools for raising awareness quickly (Imran, Castillo Diaz, & Vieweg, 2015). Using a social media tool such as Twitter, an assigned person with a digital device (such as a smartphone or tablet) and an Internet connection can rapidly disseminate messages viewed globally.

Sending a “tweet” on Twitter is a modern form of having a news conference, and the audience may incorporate people from different countries and even different continents. An advantage of using a platform such as Twitter, is its rapid response speed. The “tweet” can be written and posted within minutes, and thousands of people can read it in their Twitter news feeds within seconds. This type of advantage makes social media a highly useful tool for quickly communicating with the public when the time is of the essence.

The advantages of social media as a tool for disaster communication have attracted the interest of scholars. For instance, Simon, Goldberg, and Adini (2015) investigated the use of social media channels for crisis response and concluded that conventional communication lines like cellular networks might be overload. The overload may result from the high volumes of information originating from dozens of agencies and organizations that are responding to disaster at the same time. Therefore, social media can serve as a tool for distributing information widely without the fear of the platform being overwhelmed by volume. Studies have been conducted within the field of crisis management and disaster response to reveal how to best deal with crisis communication especially after significant events such as terrorist attack (Simon et al. 2015, Spicer, 2013). Government and non-government agencies and organizations that responded to the major disaster events were either mentioned as a “best practice” example or “poor practice” example.

In traditional disaster communication (before social media), it took an organization or agency about 48 hours to take action after the occurrence of a disaster (Olsson, 2014). Limited technological possibilities and lack of inter-agency connections constrain response time. Olsson (2014) asserted the 21st century “standard” for responding to a disaster or a crisis has significantly reduced response time due to the increasing role of social media and other advanced communication tools. In a world which information might disseminate within minutes or even seconds, the public has come to expect a response in less than an hour. If the organization or agency does not provide a meaningful response within this compressed timeframe, the perceptions of their action by the public quickly become negative. Consequently, to provide a quick and significant response, many for-profit organizations have established particular policies for communication with the public through social media, and public service organizations are following suit.

The research literature about disaster relief communication and the use of social media indicates that the importance of disaster communication is known; however, the extent of social media use in disaster communication, and the factors that affect its application is not known. When a crisis event occurs, people adopt an active information-seeking role (Olsson, 2014). To meet this need, crisis managers have turned to traditional and new media tactics online (Bundy & Pfarrer, 2015). Social media gives the audience unprecedented control over what they read, the way(s) they respond, and whether they choose to act (Alexander, 2014; Bleiberg, 2013; Bundy & Pfarrer, 2015).

Communication activities commonly influence public reactions, either on the venue or social media. During the Boston bombings, for instance, social media was used as the platform for communication with the public. People received first-hand unfiltered data directly from eyewitnesses of the event (Volpp, 2014). However, social media user’s channeled incorrect data to the public and this unsubstantiated information created confusion among journalists, broadcasting stations, and newspaper reporters. The mainstream media had to undertake a careful analysis of each claim to ensure it was accurate and relevant. But the confusion was resolved once an official report from the scene was released. The official statement contradicted most of the information shared on social media (Borah, 2011).

In this specific instance, the wrong reports, which were influenced by social media, caused criticism of most of the news agencies, journalists, television stations, radio stations, and online newspapers that had reported incorrect information (Roller, 2015; Volpp, 2013). Using social media, people can access information on emerging issues and capture the unfolding of events through social media platforms. These social sites have grown from Friendster and Myspace to the most popular current platforms that include Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, Flickr, and Foursquare (Hajli, 2015). The evolution of social media has led to a faster spread of messages and the ability to minimize harm and the number of fatalities in crises scenarios (Hajli, 2015).

The concern lies with the propagators of such messages who have no skill in disaster and risk communication and consequently confuse with their words. Nonetheless, professional agencies are quickly adapting to this mode of communication (Alexander, 2014). Many authors have investigated the application of social media in day-to-day operations. However, they have not explored it from the perspective of emergency and crises communication (Alexander, 2014). Social media communication has overtaken the traditional communication modes, and thus, its impact and adaptability is in need of assessment (Alexander, 2014)

The question regarding the most effective social media strategies for disaster communication and utilization are best answered by investigating the current methods used by emergency management organizations. By comparing these methods, one can identify common patterns and obtain information from sources that use these modes when faced with real emergencies (Rhodes, 2014). This approach can also determine the response of the public to each communication strategy.

Statement of the Problem

The current body research on the impact of social media in disaster communication is still limited because these tools do not have a long history of being used in these circumstances. Many researchers have concluded that social media is effective in improving disaster communication, but most use a small number of organizations for this analysis. The present study was designed to expand knowledge with regards to the impact of social media in disaster communication. Also, the current research was also designed to characterize the attitude of emergency management (EM) toward social media usage, the perception of its usefulness, and its role in the advancement of the profession of EM.

While it is a reasonable expectation that the platforms such as Facebook and Twitter would be a helpful addition to government and non-government disaster relief and communication strategy, the present study was an effort to measure the extent of the utility of social media in such instances. The perception of social media by EM reviewed in some studies, but the evidence provided by them was limited to general attitudes towards the platforms. The contributions of social media to the development of the EM profession have been mostly unexplored by academics.

Purpose of the Assignment

The purpose of this study was to investigate the impact of social media communication for EM professionals on emergency and crisis communication. Surveying EM personnel involved in managing a crisis allowed for characterization for how these individuals adopted social media platforms (Haataja, Laajalahti, & Hyvärinen, 2016). Results add to risk communication subject matter (Semple, 2009).

In recent years, scholars have begun to assess the way people perceive crisis response strategies (Coombs & Holladay, 2008). The stakeholder’s understanding of crisis response has the potential to influence whether or not a person follows the information provided during a crisis when broadcast through social media. Positive perceptions of an emergency response may help EM personnel mitigate the effects of a crisis, while negative perceptions may intensify these effects. Many factors influence perception and a disaster responder has the ability to use them to reduce or aggravate stakeholder’s reactions during a crisis. These reactions can range from the way stakeholders interact with the organization after the crisis (stop buying an organization’s product because of negative word-of-mouth communication) to how they respond to critical survival information during a disaster such as a flood or a fire (McDonald, Sparks, & Glendon, 2010). If a crisis response is well-received by a crisis victim, they will be more likely to follow the instructions given over social media platforms (McDonald, Sparks, & Glendon, 2010).

Another factor that influences perception is the inherent uncertainty that accompanies a crisis. When there are high levels of risk, it can be difficult for EM personnel to provide instructions that victims follow because victim's decision-making processes become clouded, which in turn slows the response to information that offers protection from harm. Collins et al. (2016) contended that the level of uncertainty is compounded by EMs are met with an aimless and seemingly endless amount of data broadcast over social media. One way to overcome the challenge of risk is to acknowledge it. If a crisis manager waits for certainty, it might mean other valuable information might not get to stakeholders on time (Reynolds & Seeger, 2005).

Therefore, it is imperative that accurate information is furnished. Rather than offering overly reassuring statements, explaining that all information is not currently available allows the crisis manager to refine the message as more facts become available (Olsson, 2014). Providing information when circumstances are unverified may reduce a spokesperson’s credibility, which translates into believability and trust. The way the public perceives a crisis response can influence the way victims respond to crisis messaging (Donahue, Cunnion, Balaban, & Sochats (2014).

In recent years, social media has changed the way the public communicates about crises, such as natural disasters and terrorist attacks (Semple, 2009). Scholars have noted that controlling information flow is one way to aid the successful management of a crisis (Wigley & Fontenot, 2011). Before social media, crisis information ideally flowed from the crisis manager to the news media and the public. More recently, however, social media users have begun to intercept this information flow and become part of the crisis communication effort by sharing and re-sharing information. In doing so, they can create a spread of information to millions of people with only a few clicks (Veil, Buehner, & Palenchar, 2011). Appreciating the motivations and barriers in its application will shed light on the possible drawbacks and areas to be improved among the professionals, and this will add to our understanding in this area (Rhodes, 2014). Results of the present study may be a useful source of information for emergency communicators on the adoption of social media strategies, hindrances, and the specifics of needed improvements.

The Significance of the Assignment

The topic of disaster risk and crisis communication is significant to the field of public safety leadership because it can determine public needs for information in emergency situations and help EM personnel develop appropriate responses. Cornia, Dressel, and Pfeil (2016) posited that effective risk communication determines the way a disaster management team will respond to the presented risk. Therefore, the present study was important because it provided an analysis of the current practices public safety authorities use about social media during crises that require immediate and effective action. The investigation resulted in a definition of the most useful methods and provided information for possible improvement. Public safety professionals, including EMs personnel, may find the evaluation of these practices useful.

The topic is significant because the disAssignment reveals effective means of communication during a disaster incident. Public safety is a priority, especially with the current acceleration of public crises due to terrorism. When faced with a disaster, communicating early and in the most efficient ways aids in public safety by directing help to the right place. Results of the present study revealed that social media could be effectively utilized to communicate with a wide range of stakeholders by providing accurate, timely information that is supported by the credibility of the agency responsible for disaster response.

Research Questions and Hypotheses

Based on information in the preceding sections, the subsequent research was an effort to answer the following research questions:

RQ1: To what extent is there a statistically significant relationship between EM professionals use social media to share or exchange crisis information with other EM professionals and pertinent members of the community? The question measures the extent to which EM professionals use the social media to share information with others.

Ho1: There is no statistically significant relationship between EM professionals use social media to share or exchange crisis information with other EM professionals and pertinent members of the community. Ho1 provides a scenario that represents lack of statistical relationship between EM professionals use social media in sharing information with others.

Ha1: There is a statistically significant relationship between EM professionals use social media to share or exchange crisis information with other EM professionals and pertinent members of the community. Ha1 affirms a significant statistical relationship between the uses of social media by EM professionals in sharing information with others.

RQ2. To what extent is there a statistically significant relationship between the application of social media in disaster and risk communications and the following: usefulness, ease of use, personal innovativeness, advancement of the profession, access to peers, and barriers?

Ho2: There is no statistically significant relationship between the application of social media in disaster and risk communications and the following: usefulness, ease of use, personal innovativeness, advancement of the profession, access to peers, and barriers.

Ha2: There is a statistically significant relationship between the application of social media in disaster and risk communications and the following: usefulness, ease of use, personal innovativeness, advancement of the profession, access to peers, and barriers.

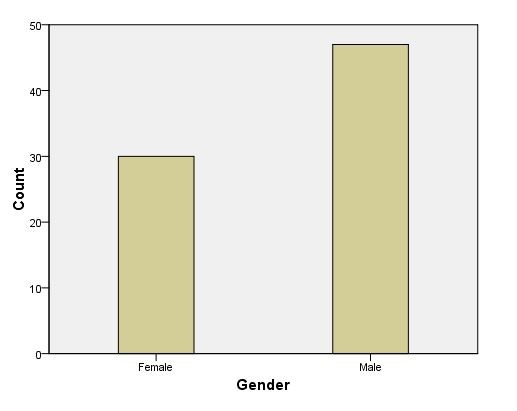

RQ3. To what extent is there a statistically significant relationship between EM demographic characteristics of age, gender, or location, and use of social media platforms?

Ho3: There is no statistically significant relationship between EM demographic characteristics of age, gender, or location, and use of social media platforms.

Ha3: There is a statistically significant relationship between EM demographic characteristics of age, gender, or location, and use of social media platforms.

The first research question was an effort to determine how often EM professionals used various social media sites to distribute and exchange information with colleagues and members of the public. This question was intended to reveal what role social media played in the professional life of EMs as well as to indicate the most frequently used form of social media was. The impact of social media on the development of the profession of EM and the ways it uses were studied.

The second question included some factors related to the use of social media for EMs: usefulness, ease of use, personal innovativeness, advancement of the profession, access to peers, and barriers to the application of social media in disaster and risk communications. Determining the role of each factor was intended to contribute to better understanding the measures needed to facilitate the use of social media by EMs. For example, prior research suggests that personal innovativeness plays a vital role in the early incorporation of social media in disaster communication strategies by fire departments (Latonero & Shklanski, 2011). Given that many emergency management organizations still limit their use of social media, personal innovativeness of particular individuals was perceived to accelerate the process of meaningful adoption and use perhaps.

The third question was related to any connection between EM demographic characteristics such as age, gender, or location, and the use of social media platforms, aspects that could be related to different patterns of use. Previous research has suggested that female EMs share more positive attitudes towards social media so they use it more to communicate risks to the public. Because most research about disaster communication and social media is relatively recent, more evidence was needed to confirm these results and to provide more details.

Definition of Terms

Definitions provide clear, specific meanings of thoughts and ideas, without a discrepancy between or among readers (Weatheringham, 2017). Surbhi (2016) advocated the importance of identifying the purpose of language usage to increase shared understanding. The following operational definitions are in use in this dissertation.

Crisis communication. Crisis communication as defined by Collins, Neville, Hynes & Madden (2016) as “the exchange of risk relevant safety information during an emergency situation” (p. 161).

Disaster. Disaster is “an accurate disrupting the normal condition of existence and causing a level of suffering that exceeds adjustment of the affected community” (Martini, 2014, p. 5).

Disaster preparedness. Disaster preparedness is explained by Sutton and Tierney (2006) as “activities, programs, and systems developed and implemented before a disaster/emergency that are used to support and enhance mitigation of, response to, and recovery from disaster/emergency” (p. 4).

Emergency manager. Emergency manager is “an emergency management position that handles the public relations functions of emergency and disaster response” (Hughes, 2014, p. 727).

Emergency management. The Emergency management is “the managerial function charged with creating the framework within which communities reduce vulnerability to hazards and cope with disasters” (Rose, Murthy, Brooks, & Bryant, 2017, p. S126).

Organizational crisis. A corporate crisis is “the perception of an unpredictable event that threatens important expectancies of stakeholders and can seriously impact an organization’s performance and generate negative outcomes” (Heradstveit & Hagen, 2011, p. 16).

Risk communication. Risk communication is “two-way exchange of information between interesting parties about the nature, significance, and control of a risk” (Lowbridge & Leask, 2011, p. 34).

Social media. Social media is defined as media that “consists of tools that enable the open an online exchange of information through conversation, interaction, and exchange of user-generated content” (Simon, Goldberg, & Adini, 2015, p. 611).

Research Design

The method deemed appropriate for the present study was quantitative, and the correct design was deemed to be correlational. Bijeikienė and Tamošiūnaitė (2013) defined the quantitative approach as “a set of methods based on quantification or measurement and that employs statistical, mathematical, and computational techniques” (p. 16). The present study was implemented using survey questionnaires that required numerical answers to questions, which is a commonly used research design. Surbhi (2016) asserted the research problem is the most important factor when determining the research design. Jang (2017) explained that quantitative research is the best utilized when a research problem results in an attempt to describe trends or make group comparisons. De Vaus (2013) explained that surveys are useful in “describing the nature of existing conditions or identifying the standards against which existing conditions could be compare” (p. 224). Babbie (2001) stated, “Survey research is probably the best method available to the social researcher who is interested in collecting original data for describing a population that is too large to observe directly” (p. 240).

The present quantitative correlational study entailed descriptive statistics and hierarchical regression analysis for hypothesis testing. Hierarchical regression analysis is also preferred because it makes it possible to test if a group of variables add to a significant level of the variance determined by a preceding set of variables (Brooman & Darwent, 2014). Experienced EM professionals, those who disseminate information (Veil et al., 2011), were surveyed through the auspices of SurveyMonkey®, an online research portal. Participants were mainly drawn from membership of the International Association of Emergency Managers and the sample was limited to those living in the US. The methodology ensured dynamic reports that could be generated by EM use of social media was addressed (Hajli, 2015).

Assumptions and Limitations

Assumptions. The following three assumptions were applied to the study.

- Each of the respondents will give an honest opinion.

- Participants will completely understand each of the terms used in the survey.

- Participants will see participation as a way to guide future practice and provide thoughtful feedback (Coughlan, Cronin, & Ryan, 2009).

It assumed that social media was frequently used when disaster struck, allowing the EM professionals to deal with situations before they become uncontrollable (Baker, 2016).

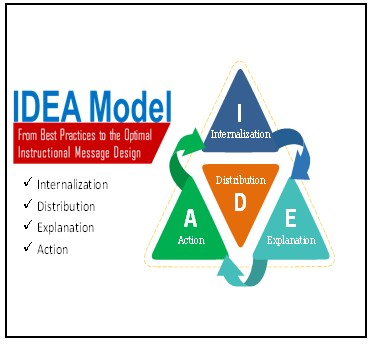

The IDEA model carries some particular assumptions that need to be identified. First and foremost, this theory assumes that an EM can gain and maintain the attention of the target audience by proving the relevance of the potential risk to them (Sellnow, Lane, Sellnow, & Littlefield, 2017). In turn, the connection is achieved by showing the chance for a particular area and pointing to that risk as imminent to generate a quick action. Second, the IDEA model assumes that if the emergency situation is concisely explained the receivers will take the desired steps. For example, according to the model, a valid risk message should include an explanation of the emergency, the way it is anticipated to develop, and how it can impact the receivers. A brief and understandable message should be sufficient to increase self-efficacy and confidence in the target audience.

Sellnow and Sellnow (2013) contended effective communication is base on internalization, distribution, explanation, and action (IDEA) model, which contains assumptions relevant to the present study. This model is being used as the primary theoretical foundation for this study. An assumption carried by the IDEA model is that if a message provides particular and meaningful actions, the target audience’s ability to protect themselves and their loved ones will be increased (Sellnow & Sellnow, 2017). The assumption is that people will look for the best action steps in emergency situations, but will be left with a sense of helplessness if those steps are not made available. Another assumption of the model is that instructional risk and crisis messages are to be distributed and easily accessible to the target audience. These IDEA assumptions may have influenced responses of the study participants.

Previous research and literature on the topic of the present study also provides some topic-specific assumptions. For example, Collins, Neville, Hynes, and Madden (2016) assumed that social media has a profound effect on disaster communication because it has the potential to increase the preparedness of the public for emergencies. Collins et al. stated that instructional risk and crisis messages sent to the public by EM empowered groups and individuals to develop particular preparatory measures and take decisive action and can help to affirm their sense of control over a crisis. Baker (2016) stated that social media made communication easier when disaster struck by allowing the EM professionals to deal with a situation before it became uncontrollable, which supports this suggestion, however, the risk of miscommunication is not be dismissed.

Limitations

The present study had limitations that should be acknowledged. First, and while recognizing that online questionnaires typically have lower response rates than those administrated via paper, the use of the survey-oriented website, Survey Monkey®, to distribute the inquiries was likely to have skewed the sample in favor of people who frequently browse the internet and use social media on a daily basis. The process is relevant for this study because the use of social media requires a certain level of internet expertise. Second, it is also worth acknowledging that people who participate in online surveys, even particular professionals, often respond to them by providing snap judgments, based on available data and may be easily impacted by various factors, including contextual and emotional responses to the questions (Andrews, Nonnecke, & Preece, 2007).

Organization of the Remainder of the Assignment

This chapter contains explanations of the foundation of the study, its purpose, significance, and design. Essential information about the importance of enhancing public safety leadership, and effective incorporation of innovative methods of communication with the public during crises as presented. Chapter 2 contains a review of the current body of research regarding the use of social media by emergency services, resulting in the identification of the knowledge gap that needs to be filled by the present study. Chapter 3 contains the methodology utilized for this research, as well as details about the sample, procedure, and method of analysis of data. Chapter 4 includes the results and determination of whether the null or alternative hypotheses should be accepted or rejected. Chapter 5 contains a discussion of the results, the relevance of the results to the theoretical framework described in Chapter 2, and implications for the current practice of crisis communication.

CHAPTER 2: LITERATURE REVIEW

The primary purpose of this research was to study the application of social media in disaster risk communications by EMs personnel. The strategy for searching the literature begins the chapter, followed by identification of the IDEA model and its theoretical application to the study project. Included in the discussion are reviews of social media and risk communication, social media disasters, primary functions of social media preparedness, and the role of the emergency managers.

Documentation

The search for information was conducted to find as many resources as possible. Inclusion criteria for the review were peer-reviewed empirical studies published within ten years before to the date of this dissertation to ensure relevance. The investigation resulted in past and present information that is necessary to justify and form a cohesive background for the study (Mujis, 2004). The search conducted in multiple electronic databases including ProQuest, Science Direct, Semantic Scholar, Web of Science, First Search, World Cat Advance Search, ProQuest Digital Dissertations, Search.Gov, and ABI/INFORM Global, Emerald Management Thinking, Science Direct Dissertation databases, and Eric Education Resources Information Center. Google’s online databases provided citations of pertinent literature. Bibliographic and reference listings accessed from appropriate titles discovered within the review process. Approximately 141 scholarly discussions about the keywords “social media and disaster communication,” “social media and crisis response,” and “social media and emergency managers,” as well as others, were researched.

The selection of optimal search terms was a result of multiple attempts to find pertinent information. For example, the word “social media and government agencies” did not produce results that could support the purpose of this study, and was discarded as a search term. The databases included abstracts, titles, and keywords of articles. Table 1 clarifies the process.

Table 1

Search Results per Database

|

Keywords |

Database |

First Results |

After initial scanning |

Added to the final sample |

|

“Social media and disaster communication,” “social media and crisis response,” and “social media and emergency managers.” |

Science Direct |

32 |

18 |

10 |

|

Web of Science |

25 |

12 |

11 | |

|

Semantic Scholar |

15 |

15 |

13 | |

|

ProQuest |

69 |

34 |

19 | |

|

Total |

141 |

79 |

53 |

Theoretical Orientation for the Assignment

After Walter Lippmann stated that the media directly influenced public opinion, the media’s effect on what we talk about and how we talk about it has been an important area of study (Wasike, 2013). Wasike termed it "framing theory." Framing theory suggests that building a system of references over time can shape the way the public feels or thinks about a subject (Reynolds & Seeger, 2005). Framing is achieving by presenting a story from a particular perspective that highlights a negative or positive feature. It is the selection of certain aspects of reality to make them more salient to promote the desired interpretation (Wasike, 2013). Framing theory is especially critical in hard news stories, such as terrorist attacks, because most of the information the public receives about these types of stories is derived directly from the media (Reynolds & Seeger, 2005). Throughout history, American news media have developed frames concerning the war against common enemies (Smith, 2013).

Sellnow and Sellnow (2013) promoted a model of communication termed the IDEA model (Figure 1). This model used as the primary theoretical foundation for this study. Based on the findings by Sellnow and Sellnow (2013) and supported by Baker, (2016).

Figure 1. IDEA Model developed by Sellnow and Sellnow.

Internalization. The authors of the model provided specific instructions on how to achieve the internalization through proximity, timeliness, and personal impact. For example, timeliness accomplished by explaining that the threat is imminent and that specific actions need to be taken to reduce or eliminate risks. Risk communicators often face a problem with insufficient motivation to engage in offering risk preventive advice to members of the public, even when they need to demonstrate the importance of acting as quickly as possible. This problem can be eliminated by stressing that the risk is imminent and can have harmful effects.

Sellnow and Sellnow (2013) suggested proximity can be achieved by intentionally focusing on the existence of high risk in a specific geographic location inhabited by receivers of the message. This technique is useful for increasing interest in the problem among the inhabitants of the area at risk, which is needed to ensure maximum public awareness and preparedness. Lastly, emergency messages communicated by risk responders should speak to personal impact by considering how the potential risk can harm the target audience and to what degree (Sellnow & Sellnow, 2013). For example, it would be almost impossible to internalize the risk of ground beef contamination for vegans because of the lack of a potential personal impact.

Distribution. Sellnow and Sellnow (2013) noted that effective communicators should have strategic choices on the delivery of the risk messages. For instance, communicators should be aware of how different target recipients prefer to receive risk-related food safety information. The variability among different audiences for acquiring information using various channels should be addressed given that some segments of society have access to modern and traditional media while others have minimal or no access to either. Effective communicators should thoughtfully select the media through which to share messages if all segments of the population at risk can be reached (Ross, 2016; Sellnow & Sellnow, 2013).

IDEA Model Strengths

Explanation. In the second aspect of their theory, Sellnow and Sellnow (2013) noted that effective risk communication should entail a description of the situation and the Assignment of its development, the scientific background, what it’s done at the moment, and expected response. The explanation should also translate science by using practical examples and familiar terms. Crisis communication should at least be (a) brief, (b) understandable, and (c) offered within the components of internalization and action (Ross, 2016). If the messages are not in line to the needs of the target audience, it is possible that it could reduce self-efficacy and confidence.

Action. Sellnow and Sellnow (2013) noted that effective risk communication should propose a meaningful Assignment of action for the receivers to help protect themselves and their loved ones. Upon understanding the risk event and having internalized the relevance, they are given suggestion about how to minimize their personal risk. In case the message does provide the appropriate Assignment of action, the receivers may encounter a feeling of hopelessness and a sense of fatalism in a problematic situation.

Message tailoring. The IDEA model of crisis communication suggests that emergency messages must be brief, understandable, and provided with components of guidelines that instruct how to act based on the given information. The main strength of this theory is the current body of research which supports the idea that message tailoring increases effectiveness and public preparedness in crisis (Eisenman, Glik, Gonzalez, Maranon, Zhou, Tseng, & Asch, 2009; Sellnow, Lane, Sellnow, & Littlefield, 2017). To tailor messages to target audiences, emergency responders can base them on gender, culture, sub-culture, learning style preferences, and other characteristics. Previous research supports the idea that ‘message tailoring’ can have a positive impact on action by members of the public.

For example, Sellnow and Sellnow (2013) suggested that messages are effective when they are in the language of the receivers. In their experiment about food safety, they presumed that the target audience understood English, but did not check whether all participants had it as their first language. The IDEA model can thus provide useful guidelines for crisis communication used by EM personnel by defining characteristics of messages that are perceived as appropriate to receivers. Message tailoring could be an effective strategy in crisis communication because it focuses on the target audience’s needs and preferences (Eisenman, Glik, Gonzalez, Maranon, Zhou, Tseng, & Asch, 2009).

Social Media and Risk Communication

Social media is being defined in many ways. Roshan, Warren, and Carr (2016) described it as “a group of Internet-based applications that build on the ideological and technological foundations of Web 2.0 and that allow the creation and exchange of user-generated content” (p. 351). In this regard, user-generated content refers to any information on social media created by users, including posts with images, text, videos, status updates, and live streams. Peterson (2014) explained social media as Internet-based applications that "promote high social interaction and user-content generation often at a one-to-many scale” (p. 350). Since 2005, the percentage of adults using social networking sites such as Facebook and Twitter has increased more than ten times. By using these sites, users can perform a wide range of activities, such as asking questions in online communities, learning about upcoming events, promoting their businesses, disseminating information, and communicating with people all over the world.

Velev and Zlateva (2012) have provided a comprehensive list of characteristics in social media that encompasses all primary and secondary functions including the following:

- Allows interactions to cross one or more platforms through sharing, feeds, and email.

- Enables communication to take place in real time or asynchronously over time, which is why broadcasters now increasingly use it.

- Involves various levels of participant engagement when one can create, view, comment, and share posts.

- Facilitates increased speed and breadth of information dissemination

- Can be accessed anywhere with an Internet connection.

- Extends engagement by providing access to real-time online events, augmenting them or extending online interactions.

- Offers one-to-one, one-to-many, and many-to-many communications.

Risk communication is an area in which social media has been playing an essential role in the most recent decade. Sellnow, Lane, Sellnow, and Littlefield (2017) defined it as “an interactive process of exchange of information and opinion among individuals, groups, and institutions” (p. 2).

One of the main purposes of risk communication is to build trust through engaging public stakeholders in the emergency recovery activities and decision-making process. The interactive nature of the dialogue between stakeholders can improve the quality of risk decisions because it contributes to better communication, which in-turn promotes collaboration (Sato, 2015). The process of disaster and risk communication, however, can be disrupted by the chaotic conditions of rapidly escalating risks. These conditions warrant a shift from dialogue to instructional messages that, for example, describe guidelines for self-protection.

Collins et al. (2016) asserted the initial step of honest crisis communication is “understanding how to structure and deliver emergency messages appropriately” (p. 162). During emergencies, people turn to social media to discover as much information as possible, so disaster management agencies should meet this need. To achieve this purpose, Donahue et al. (2012) argued that the language used by teams of EM should address maximum useful factors, including the stage and severity of the situation. For example, as the severity of the crisis intensifies and the level of threat(s) increase, any direct public guideline or recommendation should be clear and informative, but not aggressive to avoid inducing panic among people. Collins et al. (2016) also recommend delivering public messages in regular intervals to help the target audience predict when the next word will appear.

In the context of best practice principles, the study by Collins et al. (2016) provided useful information. Collins et al. recommended that the messages sent to the public by EM teams should empower groups and individuals to take decisive, thus helping to affirm their sense of control during a crisis. This recommendation corresponds to the official guidelines released by the European Centre for Disease Control (CDC), which also advises emergency management services to provide communication. It gives people with a chance to engage in decisive action because it will “reduce anxiety and can restore a sense of self-control” (Collins, Neville, Hynes, & Madden, 2016, p. 162). Barry, Sixsmith, and Infanti (2013) supported this statement by suggesting that the actions advised by disaster response organizations may be preparatory or symbolic, such as developing an escape plan to help citizens to relate to the disaster they are experiencing. Collins et al. (2016) and Barry et al. (2013) proposed the following best practice guidelines for risk communication:

- Deliver clear and consistent messages.

- Empower receivers to make better decisions

- Ensure that emergency management organizations utilize multiple social media platforms to reach the broadest population, including marginalized groups, communities, and minorities.

- Provide the public with accurate information that shows the real risk of level because being casual in emergencies may lead to negative consequences for affected individuals.

- Call for avoiding inappropriate actions such as looting and rioting.

- Minimize the formation of rumors by being regular.

- Be as flexible as possible to suit every scenario.

In addition to these critical factors, EM organizations are also advised to listen to the feedback provided by receivers of information and adjust their messages accordingly. Given that members of the public have more access to sources of information than ever before, the need to remain trustworthy is also something that EM personnel should consider (Barry et al., 2013). For example, they need to be clear and provide accurate messages that meet the information needs of their target audience, without patronizing it or downplaying risks. This strategy helps to structure message formulation and must remain constant at the time the emergency is over.

Barry et al. (2016) argued that "best practice principles of crisis communication via social media are effective because they remain focused on the needs of the audience” (p. 163). If a team of EM personnel shares sufficient and accurate information on time, the members of the public will have more confidence in the messages and make the best possible decisions. These principles are especially important because people do not want to have to select one of many social media messages provided by government agencies, but want the best and correct information (Reynolds, 2005).

The importance of tailoring disaster communication is demonstrated, by the results of a study by Eisenman, Glik, Gonzalez, Maranon, Zhou, Tseng, & Asch (2009). This group of researchers investigated ways to improve Latino disaster preparedness using social networks. Eisenman et al. determined Latino communities in the US are often left out of notifications and information because most disaster preparedness programs are tailored to mainstream easy-to-target audiences, and are primarily in English. New Latino immigrants, those who do not speak English, and those with weak Internet access, are poorly prepared for severe emergencies and are therefore at an increased risk (Einsenman et al., 2009). After testing a culturally sensitive disaster preparedness program in California, Latino communities that included culturally relevant, Spanish-language disaster communications distributed via social media, Eisenman et al. were able to increase the overall preparedness in this difficult-to-reach population. Their results demonstrated the significance of culturally appropriate disaster information for reaching diverse communities that are often left out.

Social Media in Disasters

Online social media sites such as Facebook and Twitter can assist in solving different problems during emergencies that include terrorist acts and natural disasters (Simon et al., 2015). In cases of a tsunami, earthquake, or other natural disaster emergencies, regular communication often experiences disruptions, or even cease to function while social media outlets remain active. Some studies have shown that the use of email and mobile phones increases during disasters. The purpose of social media also increases and even surpasses some traditional methods of communication, including fixed phones (White, 2014; Panda, 2012). In addition to individual citizens and sizeable public emergency response services, the use of social media is also used by many non-government organizations to inform their workforce about disaster outcomes and relief.

Most of the scholarly investigation regarding social media during disasters has centered on its role as a news source. Naturally, the amount of information circulating on social media is enormous. It can be produced quickly and disseminated across thousands of devices regardless of location. Sadri, Hasan, Ukkusuri, and Cebrian (2017) found that social media can become a reliable source of information when power outages severely disrupt the functioning of TV stations and landlines. People expect constant advice and information, not only during disasters but also in the wake of disasters to ensure that they are prepared in advance to respond to an emergency situation. During the period of accident, the mainstream conversation joined not only by emergency responders and victims but also people who have heightened concerns about their loved ones who could be affected by the event.

Agencies and organizations responsible for emergency response are currently using the opportunities provided by social media during disasters for communication; for example, they can instantly broadcast and amplify emergency warnings to the public (Velev & Zlateva, 2012). Social media is being increasingly considered a reliable channel of communication that allows communication with many people. However, many scholars including Velev and Zlateva (2012) and Qu, Huang, Zhang, and Zhang (2011) have confirmed that the most desirable role of social media in the wake of certain emergencies, such as natural disasters, is still unclear, but it could be of great value. It can connect displaced family members and friends, provide information about the unclaimed property, help find the correct direction for bodies, offer information about aid centers, give awareness to people outside the affected areas, generate donors and volunteers, and provide helpful information to people pre- and post-disaster.

White (2014) described how social media is used before, during, and after disasters, which was included in the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) reports. Specifically, White (2014) found that social media “gives disaster management organizations a means to communicate with the public to provide them with a plan for what to do if an emergency develops” (p. 4). White, listed four primary ways for uses of social media before a disaster:

- Keeps the public informed on one location and movement of potential hazards.

- Identify reliable information sources on a disaster incidence.

- Advises the public on how to prepare if an emergency occurs.

- Provides the public with confidence that the disaster management organization is completely capable of conducting proper emergency response if required.

The primary reason provided by White (2014) for why emergency responders should use social media is because it gives them a way to get vital information out to the public quick and efficiently. Below are the proposed methods in which social media is used during a disaster, as described by White (2014):

- Provides the public with the latest information on road closures.

- keeps the audience aware of areas they should avoid visiting.

- Informs the public about evacuations in affected areas.

- Reveals incorrect information and rumors about emergency response and disaster.

- Keeps affected individuals aware of the actions that are being taken to assist them.

Social media is also useful for emergency responders after the disaster.

- During the process of normalization, it can be used to provide information on recovery efforts and available resources for affected individuals.

- Assures survivors in the support by emergency responders.

- Offers the public with information on the recovery effort.

- Helps to reunite families who have separated during the disaster.

- Raises awareness of non-profit organizations looking to assist with the recovery.

Limitations and Weaknesses of Social Media

In Crisis Communication

Previous research revealed some limitations and weaknesses of social media in the context of crisis communication. For example, White (2014), Zeng, Starbird, and Spiro (2016), and Latonero and Shklovski (2011) suggested that social media platforms should be considered by emergency response organizations to ensure effective communication with the public during crisis scenarios. White concluded that the limitations should not persuade an organization to abandon using social media because “the benefits appear to outweigh the drawbacks” (p. 5) significantly. Analysis of the limitations and weaknesses revealed the following results.

Non-use of social media. The first potential limitation that can undermine the effectiveness of social media in crisis situations is the non-use of social media (White, 2014). For example, older generations may not be sufficiently familiar with the technology or may lack the skills to operate it. They may feel more comfortable using conventional communication channels, such as television and radio. Therefore, a disaster management organization should consider using both traditional media and social media to maximize the reach and ensure that older generations have an opportunity to obtain information from conventional resources.

Non-use of the Internet. The second potential limitation is the non-use of the internet. Although the vast majority of people today have a Smartphone and a reliable internet connection, there are still many individuals who do not have access to this worldwide network. Besides, about 36 million Americans (15% of the total population) report not using the internet (Bennett, Stewart, & Atkinson, 2013). While this may sound surprising, recent research by Horrigan (2014) revealed that 29% of Americans had low levels of digital skills and 42% reported having moderately good digital skills. These findings suggest that almost one-third of the American population may lack sufficient skills to obtain information from social media during crisis situations.

Horrigan (2014) found that those with low levels of digital skills “tend to be older, less educated, and have lower incomes” (p. 5). To illustrate the divide in the use of the internet by different population groups, Horrigan conducted a survey asking a random sample of participants about their digital skills and internet browsing habits. Only 49% with self-reported low digital skills visited a government website recently, while the same reported by 89% of people with high levels of digital skills. Therefore, it is essential to consider that a large percentage of the population may not have access to social media in crisis situations.

Rumors. The third critical limitation of social media that needs to be considered by crisis management organizations is ‘rumors.’ Inaccurate information and stories can spread over social media very quickly (Ozturk, Li, & Sakamoto, 2015; Zubiaga, Liakata, Procter, Hoi, & Tolmie, 2016). In emergency situations that create confusion, some people tend to believe false information, so it is crucial for disaster management organizations to identify and correct all false information circulating on the internet as quickly as possible. For example, an organization may advise the public to disregard unreliable reports from individual users of social media, and even some organizations, unless official reports and statements support them.

Prior research has revealed the impact of rumors and misinformation and how content and user features could be associated, with public attention on social media. For example, Zeng et al. (2016) found that content and user characteristics played an important role in determining the care given by a user to a social media message. Zeng et al. stated that several features affected the interest of social media users to rumors on Twitter: rumor stance, uncertainty, and right or false news and sentiment. First, the messages that featured a clear position on the story were re-tweeted more than those without it (Zeng et al., 2016). Second, if authors of tweets about crises expressed uncertainty, their messages also received insignificant attention. Third, the scholars found that tweets with extreme sentiment tended to be re-tweeted more often and faster compared to emotionally neutral ones.

Concerning the impact of false information on social media, previous work has also warned about the need for quick correction. For example, Starbird, Maddock, Orand, Achterman, and Mason (2014) reviewed the effect of rumors during the Boston Marathon Bombing and found that they were persistent and continued to propagate at low volumes after corrections from reliable sources faded away. Users cited a false Twitter rumor about an 8-year old girl running in the marathon, who was reported to have died in the attack. According to the analysis completed by Starbird et al. (2014), the original rumor was re-tweeted 33 times, but it then began to spread in many forms from different authors. Correctly, the scholars identified 92,785 tweets related to the story, 90,668 of them were false, and only 2,046 were corrections. The peak correction occurred roughly within the same hour interval as peak misinformation, which suggests a quick community response. Findings also indicated that rumors spread quickly, and continue to appear on social media even after corrections has posted. It is clear that emergency managers working with social media should thoroughly monitor the information to stop the spread of misinformation following a disaster.

Unrealistic expectations. White (2014) determined that one of three Americans “expects help from a disaster management organization within an hour of their posting information on social media” (p. 6). Given that the vast majority of the public also expect all crisis response organizations to monitor social media in emergency situations actively, the expectations from reliable sources of information are high. However, in the case of a crisis, an organization responsible for informing the public may simply be too busy to monitor communications outside their channels, so responding to every person over social media may be unrealistic (Imran et al., 2015). Some people can become frustrated, and even agitated if they do not receive a quick response to their requests. These individuals may perceive that the organization is not correctly doing the job since it fails to provide a timely response. This limitation should be considered by emergency response services to prevent agitation and frustration in individuals hoping to obtain answers via social media.

Unrealized potential. Some disaster management organizations and agencies still do not use social media for crisis communication. Haataja, Laajalahti, and Hyvärinen (2016) suggested that, by ignoring its potential in managing disasters, they are limiting the tools they have to ensure a proper response. One of the prominent examples of a failure to maximize the use of social media during disasters was the Japanese government’s response to the 2011 Tohoku earthquake and tsunami. Some scholars researching the problem, including White (2014) and Panda (2012), found the use of social media tools as a part of the warning system was mostly ineffective. Panda (2012) wrote that the use of social media was not perfect because “Japan’s heavy bureaucratized system hindered the faster communication of information to people” (p. 64). As a result, lack of information created fear and uncertainty among Japanese citizens, who afterward expressed their hope that the government would not in the future deceive them and contribute to speculation and misinformation in news reports sent around the world (Doan, Vo, & Collier, 2011).

After recognizing that cell phones and landlines were failing, the affected Japanese citizens used social media sites that were up and running. For example, the mayor of Minamisōma, one of the affected towns in the area, filmed a video of a destroyed neighborhood and pleaded for help from the Japanese government. This video has been viewed over 500,000 times on YouTube since it was posted and showed, once again, how effective social media could be in raising the awareness during disasters (White, 2014).

Major Functions of Social Media

Preparedness and Response

The vast majority of the studies on social media’s role in disaster communication was part of a general effort to evaluate the effectiveness of social interaction using hand-held digital devices. As the result, many studies have focused on such aspects as the extent to which people use social networks, how social media interacts with conventional sources of information, how people perceive social media networks and what their communication preferences are, and the potential of these networks for use in disaster situations (Imran et al., 2015). Researchers that addressed the use of social media in crisis response and disaster risk reduction defined several essential functions, including listening, monitoring, integration into emergency planning and crisis management, crowd-sourcing, crafting social cohesion, and research (Alexander, 2014). Each of these functions defines the ways in which social media is studied as a tool for crisis preparedness and response.

A listening function is the first element regarding social media preparedness and response. For example, social media provides an opportunity for the public to voice their concerns and opinions about emergencies and crisis. Before social media, most people did not have this opportunity. Alexander (2014) claimed that social media networks enabled a remarkably democratic form of participation in a national and international debate about disasters and crises. Public agencies responsible for disaster response and communication of information to the population can use concerns expressed on social media to define particular aspects of their mental and emotional state (Johansson, Brynielsson, & Quijano, 2012). Social media allows authorities to listen to the public during emergencies and to collect different output.

The next important function reviewed in the literature is the monitoring function. The primary goal of the monitoring function is to gather information from the public and define ways to manage and improve their reactions. For example, Bird, Ling, and Haynes (2012) claimed that inaccurate and harmful information is often enhanced in social media reports, and can negatively impact the perception of an emergency situation by the public. As a result, the effectiveness of disaster management, as well as the attitude to emergency preparedness by the public could be profoundly affected by inaccurate information on social media (Medford-Davis & Kapur, 2014). To prevent the dissemination of false information, and rumors, appropriate agencies and organizations should use social media to provide an accurate portrayal of emergency preparedness and response (Medford-Davis & Kapur, 2014).

Similarly, integration into emergency planning and management of crisis situations remains a critical element in the future of social media. It is another significant use of social media described in the current body of research. Alexander (2014) asserted that more than 80% of the US general public viewed social media as an appropriate source of information for both government and non-government emergency response organizations. The immense potential of social media to provide helpful information is therefore widely recognized by the public as an opportunity to enhance disaster preparedness and management. The collaborative model of emergency management and communication involving social media is accepted as an appropriate one, instead of strict bureaucratic systems used by many government agencies (Alexander, 2014).

The additional element of preparedness is crowdsourcing and social cohesion. It is crowdsourcing in particular that contributes to creating social cohesion and is the next significant function performed by social media in disaster communication. Given that, in many cases, the first responders are citizens, their contribution to mobilizing leadership and support systems is critical for an adequate response to a crisis. By allowing people to participate in public response, social media fosters a sense of identification with the local and online communities. In many cases, it enhances voluntarism by increasing the readiness and awareness of emergencies in voluntary organizations. One of the most recent examples of how social media was used to mobilize a large number of volunteers occurred in March of 2014, when 2.3 million people “joined the search for missing Malaysian Airlines flight MH370 by scanning more than 24,000 square kilometers of satellite imagery uploaded to the Tomnod website” (Whittaker, 2015, p. 359).

Scifo and Salman (2015) contended citizens “can be involved in emergencies during both preparation and response phases” (p. 3). Preparedness will not only improve their ability to manage the emergency situation until the arrival of responders but also help to collaborate with them as well. Scifo and Salman conducted a comparative analysis of how social media was used to engage volunteers in several countries and found the following. In Turkey, there were many government agencies and volunteer organizations actively engaged in preparing citizens for disasters using social media, such as Twitter, Instagram, and YouTube. Italy had an even more advanced network that included the National Civil Protection Service (NCPS) that featured “2,500 voluntary organizations and 1,300,000 million volunteers, 60,000 of whom can be deployed within a few minutes, and 300,000 in a few hours” (Scifo & Salman, 2015, p. 16). In Germany, there was also a comprehensive network of volunteer organizations that used social media on a regular basis, including the Standing Conference for Disaster Reduction and Civil Protection (SKK), the German Fire Brigades Association (DFV), and the German Committee for Disaster Reduction (DKKV).

Public Expectations of Disaster-Related

Information on Social Media

Current researcher's work was analyzed during the literature search and addressed the topic of public expectations of information related to disasters and emergencies, as provided by responders on social media. Some studies reviewed expectations regarding the types of data, social media use by authorities, and critical infrastructure operators. Petersen, Fallou, Reilly, and Serafinelli (2017) stated that the public expected to be informed about the dangers to their lives and properties at every significant stage of the disaster cycle. These findings were supported by Perko et al. (2014), who studied nuclear emergency preparedness and found that citizens needed to be able to find out about the event that occurred, possible scenarios of how authorities would deal with the situation, and what steps they were required to take to mitigate the risk to themselves and their properties.

Second, there was already a significant body of evidence to claim that the public is turning to social media networks to obtain the latest information from emergency services. In addition to having an active social media account, citizens also expect a quick response if they contact the services via sites such as Facebook and Twitter. This finding suggests the need to have an active social media team to respond to citizens and keep them updated during emergency situations. It also corresponds with the results of Reuter, Ludwig, Kaufhold, and Spielhofer (2016) who suggested that more than 40% of European citizens expected emergency services to provide an answer to their social media inquiries within 1 hour.

Third, in contrast to police departments, in fire departments and other emergency services there remains limited scholarly research exploring public expectations from individual emergency managers during crises (Petersen et al., 2017). People expect as much information as possible, and as fast as possible, but there are more critical areas to address that would improve the use of social media by emergency managers. For example, the influence of factors that include ease of use, personal innovativeness, and access to peers, remains mostly unexplored. Moreover, there is a need to study the relationship between EM demographic characteristics, such as age, gender, or location, and the use of social media platforms to define which ones are more impactful in regards to meeting the expectations of the public and needs of EM personnel concurrently.

Role of Emergency Managers Using Social

Media in Disaster Communication

With the advent of the internet and especially social media, both government and non-government organizations and agencies responsible for public safety, need to adapt to a changing media environment to ensure that credible and trustworthy information is appropriately delivered to maximize the possibility of a successful outcome (Kelly, 2014). If properly utilized, social media can be leveraged to help build trustworthy relationships with the public, coordinate emergency response activities, and establish credibility. Much public information and emergency managers see social media as an additional media channel for distributing their messages to the public (Slagh, 2010). As described by Martini (2014), the public also support the usefulness of social media sites; for example, according to the results of a survey of US adults, 69% of the respondents claimed that “emergency responders should be monitoring social media sites” (p. 2). Thus, respondents have to be aware that people are trying to communicate with them and contribute to disaster management and relief.

Many researchers have investigated the attitude of emergency managers (Hughes, 2014; Reuter, Ludwig, Kaufhold, & Spielhofer, 2016; Shiel, Violanti, & Slusarski, 2011). For example, Hughes sought to understand better how EM personnel engage with social media and found that most of the participants demonstrated a positive attitude toward Twitter and Facebook. Some of the EMs personnel in the Hughes study found the Twitter search functionality useful to find new and critical information about disasters. They stated that one of the most essential advantages of employing social media tools was shortening the response time that allowed disseminating information to the public. The work of Kelly (2014), supports the findings that state EM personnel saw value in social media and agreed that at least one individual should be dedicated to cover every event using social media.

The most striking conclusion of studies on the attitude toward social media conducted in the early 2010s was insufficient understanding of the power of the phenomenon. For example, Shiel, Violanti, and Slusarski (2011), in their survey of fire department public information officers, found that they did not possess an understanding of the universal power of social networks and were “underutilizing it for inappropriate reasons” (p. 65). Among the most common reasons provided by participants in the survey were the lack of training, lack of resources, or inadequate time to complete training. The researchers concluded that social media was not implemented strategically at the departmental level and recommended that fire departments review their disaster communication strategies to add this new and useful tool. They suggested that emergency response agencies have to trust the public on some level to manage emergencies, so more should adopt social media communication.

These findings were supported by the study conducted by Latonero and Shklovski (2011) who interviewed public information officers of the Los Angeles Fire Department. According to the researchers, the extent to which social media is integrated into the organization’s departments depends on the enthusiasm of its members. One of the interviewed officers reported having learned to use social media before the major government agencies incorporated it and even created the first website for the Los Angeles Fire Department. Latonero and Skhlovski (2011) concluded that the do-it-yourself approach was paramount in including social media in disaster communication because the skills developed by that officer allowed him to “develop a reputation and to maintain source credibility” (p. 9).

The current strategy for disaster communication in the Los Angeles Fire Department includes the use of social media by public information officers. Latonero and Shklovski (2011) discovered many examples where the organization leveraged Twitter to monitor and gather information from citizens. According to the Los Angeles Fire Department officers, one method they use to validate the information posted by social media users was personal monitoring of keywords related to crisis. Their perfect vision for the future of social media use by emergency departments involves a sophisticated system in which each citizen is able with sufficient means to transmit information directly to emergency managers. This study (once again) supports a positive attitude of emergency managers toward social media and its ability to improve disaster communication.

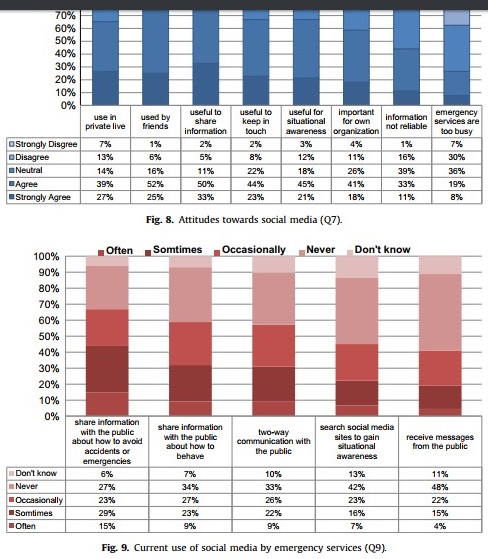

More recent studies have demonstrated that the perception, as well as the use of social media by emergency response agencies, is changing. For example, Reuter, Ludwig, Kaufhold, and Spielhofer (2016), who interviewed 761 emergency service staff members across 32 European countries, completed one of the most comprehensive surveys and generated some interesting findings. The researchers discovered that female emergency service staff were “much more open-minded and had a more positive attitude towards social media than their male counterparts” (Reuter et al., 2016, p. 101). Also, the researchers determined that younger service staffs in the sample were more positive towards using social media than those aged 50 and over. Keeping in touch with citizens, sharing information with citizens, and improving the overview of the situation, and therefore increasing situational awareness were the main potential use cases identified in the sample. However, 27% of the sample also reported that they were too busy to analyze the data from social media.

Data about the current organizational use of social media provided by Reuter et al. (2016) painted a different picture. Almost the half of the sample claimed they shared information with the public only ‘sometimes’ (Figure 1). Interestingly, 34% of organizations never had actually shared any information with the public during disasters. Among the EM personnel reporting that their agency did not use social media, several provided a concrete reason: that the broader adoption of social media by emergency response agencies required more time and communication concerning disasters. However, It was well-known that social media use was set aside for state authorities, who might not want to delegate this role.

Figure 1: Current use of social media by emergency services in Europe. (Reuter et al. (2016)

Challenges Hindering the Use of Social

Media in Disaster Communication

The adoption of a social media strategy for disaster communication is not without some challenges (Hughes, 2014; Latonero & Shklovski, 2011; Spicer, 2013). Emergency responders face many challenges, including increased expectations to provide accurate and timely information, keeping pace with rapid advances in social media, and mounting pressure to consider the use of content generated by the public. Also, the sheer amount of data generated during a crisis event may be overwhelming and present significant challenges for analyses and decision-making (Imran et al., 2015; Roshan et al., 2016). For example, the public created more than 26 million social media messages during Hurricane Sandy, which is far too many for emergency managers to analyze without adequate assistance (Hughes, 2014). Additional challenges come from the lack of understanding about how to communicate via social media during a crisis (Li & Goodchild, 2012).

In spite of the increasing importance of social media in crisis, many researchers emphasized that many organizations still do not fully understand how to use this tool during an emergency (Latonero & Shklovski, 2011; Roshan et al., 2016). The lack of understanding can lead to adverse outcomes, such as mishandling of a crisis or undermining the reputation of the responding organization. Even those organizations seeking to adopt social media face a severe problem: the practical matter of formally incorporating it into emergency management practice. Liability Concerns

The incorporation of social media networks as an information channel in emergency response effort leads to liability concerns (Lindsay, 2011). In case of a disaster, both emergency management action and inaction can result in property damage, injury, and even death, potentially leading to lawsuits against the organization. Therefore, the information dispersed by emergency managers must be accurate, relevant, complete, timely, and must not cause any additional concerns such as violation of citizen privacy (Lindsay, 2011). However, as described above, the amount of information that emergency managers must manage during a crisis can be quite large, so that a complete analysis may be impossible. As a result, it is problematic to determine what information meets all standards and does not cause any ethical and legal concerns. Besides, another potential liability concern emerges with increasing public expectation that an agency will provide an appropriate response through social media to answer numerous requests. Currently, complete monitoring of social media requests and messages is achieved only with the help of advanced technological tools, which are not accessible for some organizations.

Changes in Responsibility and Role

Before the incorporation of social media as a tool for emergency communication with the public, organizations have established response procedures. Houston, Hawthorne, Perreault, Park, Goldstein Hode, Halliwell, and Griffith (2015) stated that EM organizations could effectively operate social media. However, some of the processes and procedures that support emergency response do not lend themselves to it. One of the best examples is an organizational structure that requires emergency managers to obtain approval from the emergency operations center manager or incident commander of their response effort before sending messages to the to the public (Oywang, 2008). The permission obtained whenever sending information to the public reduced the effectiveness of disaster communication. Moreover, some EM personnel may disagree with the position of other managers on the message(s) to the public.

These findings are supported by earlier work from Latonero and Shklovski (2011). They interviewed public information officers in the Los Angeles Fire Department and found there is a vast disconnect between their activities and the organizational support structure within which they worked. Organizationally, they were expected to manage both traditional and social media communication, an overwhelming responsibility. Latonero and Shklovski (2011) provided a quote from one of the officers to illustrate the situation: “We are drowning in data down here, and we’re thirsting for knowledge, just like the people” (p. 12). The scholars concluded that the leadership of the Los Angeles Fire Department might not have fully grasped the value of social media for assisting the daily activities of public information officers and firefighters, nor the volume of work it would require when added to normal operations.